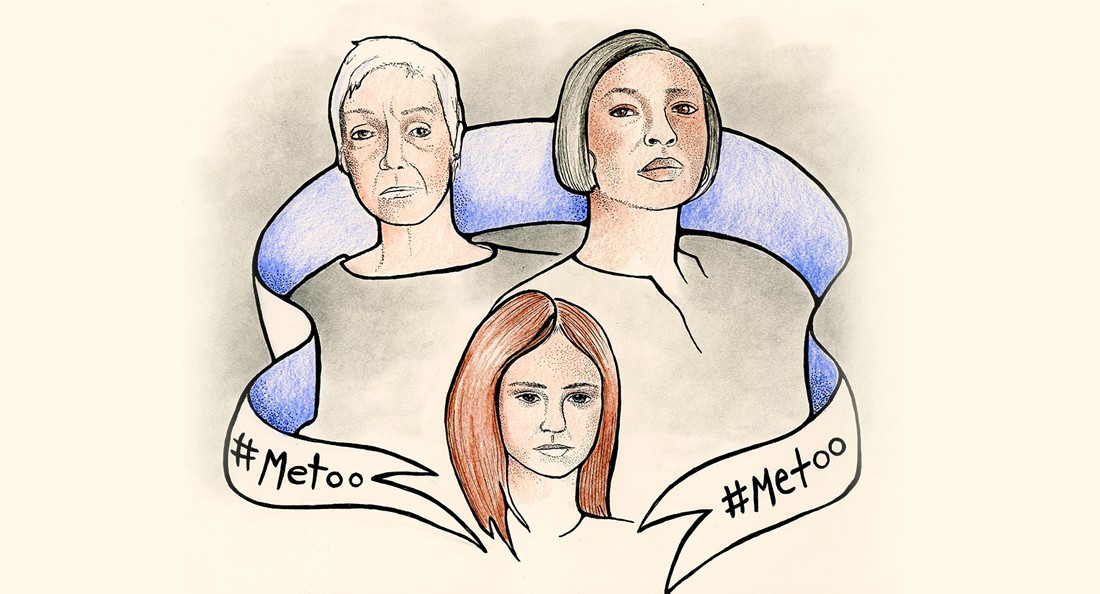

Collective healing

In the MeToo era, those who speak out help those who can’t

I requested Chanel Miller’s book from the Millennium Library minutes after I read a news article revealing both her name and the work’s release. Her memoir was quite literally the next chapter following years of media coverage that referred to her only as “Emily Doe” or, in other cases, as “Brock Turner’s victim.”

Know My Name, released in September 2019, is a candid account of the night Miller, then 22 years old, was raped at a frat party, as well as the police investigation, court proceedings and public scrutiny that followed.

This work is one of many in the MeToo era that exposes abusers while prioritizing the stories, achievements and healing of survivors. In a New York Times book review for Know My Name, Jennifer Weiner asks readers to consider the “women who’ve been sidelined or silenced or who have abandoned their chosen fields” after they were assaulted or harassed by the likes of Louis CK, Charlie Rose or Harvey Weinstein.

“And what about the would-be comedians or actors or writers or journalists who were raped or assaulted as young women, and who were stopped before they got started, silenced before they could speak?” she asks. Weiner imagines those stories “like a drowned library, an Atlantis of movies and books and

performances that will never be.” Miller’s book, however, is “one of the rescued, a memoir by a writer who dived down into the darkness, pulled herself up and out and laid her story on the sand, still dripping, with its sharp edges intact.”

I don’t often call myself a “survivor,” because, to me, the term implies that I’ve moved past my trauma and have somehow come out stronger on the other side. But as a victim of sexual assault – and, frankly, as a woman living in our current cultural and political climate – stories like Miller’s are essential.

While reading Hunger and Roxane Gay’s account of the horrors she experienced at 12 years old, I began processing what happened to me when I was 22. I devoured all the Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison works I could, and while I haven’t been able to share my own story yet, I was finally able to

unfollow my abusers on Instagram – a small action that had a profound impact on my mental well-being.

To be clear, survivors don’t owe the world anything. No one should be coerced into recounting their experiences or forced into naming and confronting their attackers. There isn’t always a rhyme or reason to when people speak up, and these things aren’t always as planned as a book deal or court case.

Last October, Kelly Bachman walked into a bar to perform standup and spotted Weinstein in the room. In an opinion piece for The New York Times, she explains her decision to call him out and identify herself as a rape survivor before beginning her set.

“When we talk about the consequences of rape, we often don’t account for the time we survivors spend healing. The time we spend finding our voice after feeling silenced. I truly believe that I could’ve been a comedian by age 19 if I had not been raped when I was 17, and then again when I was 20, and again when I was 23,” she writes. However, at 27, she says she finally felt strong enough to use her voice.

“Laughter isn’t just medicine; it’s power,” she concludes the piece. “If I can laugh at the monster from my nightmares, if I can laugh at the most powerful predator in the entertainment world, maybe my pain doesn’t control me as much as I thought it did.”

Toronto Star journalist and producer Morgan Bocknek sought to regain power when she decided to meet face-to-face with the two men who attacked her. “I met with both men, years apart, and watched them cry over their treatment of me. I heard them apologize and ask for forgiveness,” she writes.

This approach is called restorative justice and brings “a victim, offender, community and sometimes representatives for either side together to discuss their needs after a conflict or crime.” Bocknek admits this process won’t work for everyone and isn’t always an option, but it helped her.

In a similar way, Jeannie Vanasco met and spoke on the record with “Mark,” who was once one of her best friends from high school, who raped her when they were both teenagers. She details their friendship and the interviews she conducted with him 14 years later in her book Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl, which Sophia Shalmiyev calls a “literary feminist miracle.”

It’s a privilege to be able to write, create art, protest and generally speak out about these injustices. Not everyone has access to therapy, legal assistance and supportive circles, nor the luxury of time to process, report and attempt to heal from the trauma they’ve experienced. But those who do often help more people than they probably know.

Nishita Jha writes for BuzzFeed News: “The measure of successful feminist action, I learned this decade, has never been only about changing laws, governments, or workplace policies. Anger itself is clarifying, because it changes us, the people who participate in it, by giving us ways of seeing: seeing ourselves as part of a collective, seeing through patterns of abuse, seeing as in witnessing each other’s lives and stories.”

I’m angry. I have been for years, and I doubt that will change before the fourth annual Women’s March takes place on Jan. 18. This specific event will focus on human rights and specifically bodily autonomy. I likely won’t be out there with signs and banners, but I’ll try to attend, smiling and occasionally crying, as I have in the past. Right now, I protest by being, and that’s okay, too. There’s no “right” way to recovery, but knowing this community exists – along with the works of brave, powerful and outspoken women like Miller, Gay and Bachman – makes the process a little easier.

Danielle Doiron is a writer, editor and marketer based in Winnipeg. She can’t eat wheat right now, so if you have any killer gluten-free recipes, send ’em over.

Published in Volume 74, Number 13 of The Uniter (January 9, 2020)