An (incomplete) queer history

Creating and occupying space in Winnipeg, past and present

Queer history is everywhere, scattered throughout all kinds of archival records. However, finding that history presented in a neatly condensed way, all in the same place without a thing forgotten is impossible. People pass away with their histories, or are written out of it.

For some, the academic language often used to historicize queerness is difficult to glean information from in an immediate way, making the knowledge contained inaccessible.

Winnipeg doesn’t have a designated gaybourhood with a storied history in the same way that Toronto, Vancouver or Montreal do, and accessing information on local history means digging through intimidating archives or reading one of the few academic texts that articulates what it means to be queer in this geography.

It’s nearly impossible to report on history in an objective way, and I feel that it’s important, as a queer reporter, to acknowledge that my own lived experience informs the way I interpret and represent my findings.

I can’t give you a complete history of local queer activism and culture, but instead, a crash course: how the opening, closing and reimagining of queer spaces, physical and abstract, have served as timestamps in our collective local memory and the ways that people are currently carving out space for queerness in the local historical canon.

As Valerie Korinek writes in her book, Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and People in Western Canada, 1930 - 1985, “Recapturing and analysing Winnipeg’s queer past complicates and enriches the city’s history. It reminds us that the experiences and contributions of queer, gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and two-spirited people deserve to be featured in prairie histories.”

As far back as the 1930s, the Alexander docks as well as the northern bank of the Assiniboine River behind the Legislature grounds (referred to as The Hill), were places populated, usually after dark, by gay men for many decades.

The northern riverbank of the Assiniboine River behind the Legislature grounds, known for many decades as The Hill.

Queer men would frequent the area to socialize and to meet other men – including but not limited to meeting up for sex, an activity popularly known as cruising.

One of the implications of occupying public space as gay men in this way was that it left people open to the threat of violence, known then as gay-bashings.

“I remember hearing stories from a friend of mine (about) being approached by bashers at The Hill and a group of native drag queens coming to his rescue. If you’re a native drag queen in Winnipeg, you’re tough,” Joey Ritchie, an antique enthusiast and gay man, says.

A series of violent assaults near The Hill in the late 1970s caused a response from local law enforcement to surveil the area; not to protect cruisers from homophobic violence but to remove them from the area upon discovery.

The 1970s saw the birth of many local queer activist organizations and advocacy groups.

Gays for Equality (GFE), founded by Chris Vogel and Richard North, was among the first of these such groups. GFE was responsible for a large amount of local queer advocacy and ran its own counselling unit.

The GFE phone lines consistently took calls from religious rural queers who were struggling with the intersection of their faith and identity, which inspired the creation of several organizations dedicated to supporting queers of faith.

There were so many queer advocacy groups and publications in Winnipeg at this time that a conference was held at the University of Winnipeg in 1977.

The Manitoba Gay Coalition (MGC) was formed shortly after the conference. The coalition focused their energy on political engagement by polling provincial candidates during the 1978 election regarding their stances on gay rights.

MGC later created Project Lambda (PL), a fundraising project for purchasing a queer community centre. In 1982, Project Lambda secured a space at 275 Sherbrook St. and opened Giovanni’s Room, a gay community centre.

Winnipeg Gay Media Collective (WGMC), assembled in 1977, was dedicated to creating local and publically accessible queer media.

WGMC created a show titled Coming Out!, which made its debut on Manitoba Television Network in 1980.

Coming Out! ran until 1994 and produced over 700, half-hour-long episodes.

WGMC also worked with the Nichiwakan Native Gay Society to create Nipoo Aspiniwin: A Cree Language AIDS Video. The host of the special episode of Coming Out! spoke entirely in Swampy-Cree, and explained safer sex practices and local resources.

The combination of increasing visibility of queer identities and successful efforts of local groups to win protective rights for queer people led to the first Winnipeg pride parade.

The parade took place on Aug. 2, 1987, and 250 people marched in the inaugural parade.

“It was wild, really surreal. There were people with paper bags on their heads. They were scared, they didn’t want their friends to know, or their families, or their workplaces to know. They didn’t know if it was going to be safe,” Ritchie says. “You’re walking around seeing people with the bags on their heads, and seeing people looking on at the parade who you knew you’d seen around at bars. It was very surreal.”

Peetanacoot Winnie Nenakawekapo (left) is a cultural support worker at Nine Circles Community Health Centre.

Nenakawekapo’s interest in community healthcare stems from a desire to care for and comfort people during the AIDs crisis.

“I used to go the hospitals,” Winnie says. “I wasn’t educated enough to know people got infected by the virus. I was fearful, but I went anyway. I wanted to know more about how to get involved and how to service the community. How to help them, how to comfort them.

“When we go to ceremonies … Albert mentioned that we don’t tell people what to wear. We tell them to wear whatever they are comfortable wearing, as long as nothing is hanging out.

“I wear a skirt, not because I was told to wear one. I had a vision. In my vision, I’m in braids and makeup, but no makeup as in lipstick or eyeshadow, but in the sense of an Indigenous person, and I wore a skirt. The skirt was royal blue with rainbow colours. I had a shawl, dancing a younger person’s dance, specifically a women’s powwow dance. That was my vision. It was not someone telling me that I should wear a skirt or makeup. It was me feeling comfortable.”

Albert McLeod (right), co-director of the Two-Spirited People of Manitoba, joined the Manitoba Aboriginal AIDS Task Force (MAATF) in 1993. The organization led the response to HIV’s impact on Indigenous people in Manitoba and introduced the use of Indigenous teachings into harm-reduction and social justice.

“In 1986, there was a US response of Two-Spirit people to HIV/AIDS, and we collaborated with them. That created a network, I guess you could say, centred around the liberation of Indigenous people and being queer.

“Growing up in the north in the early ’70s, it was a very heteronormative society.”

McLeod recalls hostile attitudes towards queer people during the early ’70s.

“In my spirit, I knew that there was something more to life, so I left when I was 19. I moved to Winnipeg in 1977, seeking out a gay culture and people.

“Then in 1979, I went to Vancouver, finding it very difficult to live in Winnipeg, (because of) the poverty, (the) lack of opportunity. In Vancouver, it was a real eye-opener, in terms of how diverse people were, how gay people were, just really that quality of life was so different there. I was there for three years and then came back to Winnipeg.

“This was all specifically around the AIDS crisis. I thought I could outrun HIV, but it was here (in Winnipeg) by 1985.

“By 1990, we had the name Two-Spirit. We adopted that term and used that term in our education, awareness and advocacy. This year, we hosted the 31st International Two Spirit gathering which really speaks to the longevity of our movement. It’s one of the oldest continuous queer movements in North America.

“I think as Indigenous people decolonize and deconstruct history and look at identity issues, we’re working alongside our siblings in doing that, but with an Indigenous queer lens. So we insert our voice into that heteronormative context that most Indigenous organizations work from and really say, ‘Well, in an Indigenous world, there is an acknowledgement of diversity in regard to gender, sexuality and tradition.’” McLeod says.

“Those of us who came out in the late '90s and the early 2000s, before the internet really became the internet that it is today, came out in this odd time. It was like we were born, like after the apocalypse and then into this new age,” Levi Foy, program co-ordinator for the Like That program at

Sunshine House says.

Foy remembers a conversation around naming the program Like That. "It resonated with me, because in the shelter, when people would come up to me, they'd be like, ‘I'm like that.’ Or ‘so and so is like that.’ And then also, because it was nondescript, then people knew that there was something else to that person.

“And then I also remember that that's how we had talked about other queer people in my community, like, ‘oh so and so is like that.’ ... And so I was like, okay, that's actually a thing that we've historically used to describe people who don't have, or who can't or won't or just, even around the subtleties of having to say the words gay and lesbian in the '90s. People weren't even allowed to say those things out loud, right?”

Foy shares how the vision for Like That came to be.

“It had to be modelled after an auntie's home. So there had to be a very loose structure, but there had to be a set of guidelines, and there had to be food, all the time. And there had to be people who had no authority, but people who you could ask questions to. And so that would be the staff ... and then from there, we just opened the doors, and people just started coming.

“We need to be a little more than just always thinking about what social services can do for us. We need to have spaces ... where are people going to generate ideas, and where are people going to get together and have these really fun and fruitful conversations about what queerness is in Winnipeg in the 21st century. And (a space that) isn't dictated by government funding; it can't be tied to any kind of people who have any kind of say over what happens in that. It has to be (community-run) and unabashedly queer all the time, ” Levi Foy says.

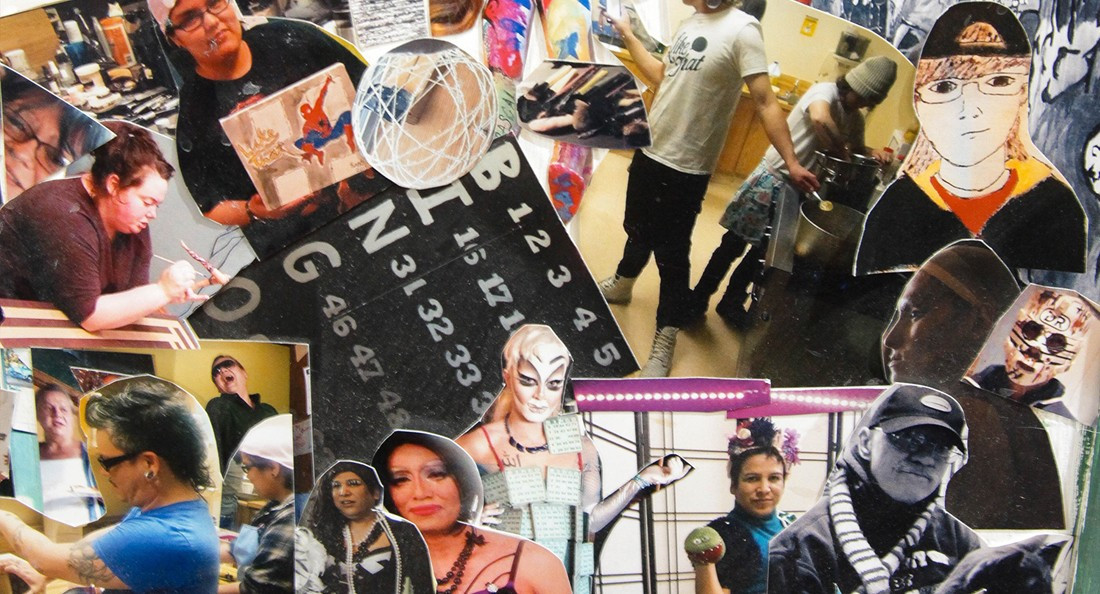

Uzoma Chioma, founder of Queer People of Colour Winnipeg (QPOC) says that the aspirations of their organization are to create space, share resources and to create community in a self-determined way.

“The hope would be that younger folks who are coming up, who would’ve never otherwise been able to see themselves represented, see themselves. That they know, here in the prairies, QTBIPOC folks not only exist, but we do really dope things. We show up for each other, we’re creative, we’re expressive, we are exactly who we wanna be. They can look to us and say ‘whatever it is I’m going through, I can get through that, and I can become whatever I want or go in the direction I want my life to take me.’

“Wherever QPOC goes, it goes. It’s not up to me to decide that. It’s meant to hopefully inspire folks to create their own initiatives. A large part of our job is to sit down with folks who have ideas and provide whatever support they need in order to get those things off the ground and to be successful.

“People have been doing this work for a long time. On some level, I might’ve gotten a little bit lucky with timing, with social media and all of that, and I’ve been really #blessed to have some pretty amazing people show up for me, and call me out and hold me accountable and help me be better, and allowing me to have the space and time and energy to feel like I can keep doing it. It’s not just me, and it’s not just going to be me. There are going to be people, and there are already people who are doing incredible things that are going to have me fade off into the distance, as it should be.

“When I was in university, the language around identity and queerness and sexuality and gender … maybe it existed, but it wasn’t at all accessible yet. To think of how quickly things are moving, it’s pretty incredible. It makes me feel very humble to think of the people who were doing that before it was ever a hashtag or cool or trendy or whatever ... before it got likes.”

When Renu Shonek surveyed the current landscape of local queer entertainment, they took note of people who wanted to introduce non-binary identities and gender fluidity to the drag scene.

Their idea to create a space for these kind of performances was encouraged by one of the original organizers of Genderplay Cabaret, Reece Malone.

“We had lunch one day, and he was like, why don't you take this? And as long as you acknowledge the roots of why it exists, and basically told me to treat it well.”

Genderplay Cabaret was a community and series of performances that ran from 2001 until 2007 and served as a platform for people to explore gender diversity through drag performance, no matter how subversive.

“Genderplay Cabaret is just that — it’s gender play.”

Shonek performed and toured in the original iteration of the show in the earlier 2000s. The troup made their way to Minneapolis, Chicago and Columbus for The International Drag King Extravaganza.

“I was somebody who was entered into this realm as a performer, and my eyes were being opened. Now my eyes are open and wanting to pass that along to other people.”

Other than creating space for people to perform, Shonek has plans on the horizon to open a QT2SBIPOC library.

Shonek feels that it’s important that the library’s content reflects literature and resources from many diverse authors, in order to illustrate that each queer Person of Colour’s experience is different and nuanced in its own way.

“It’s about not being an academic but still wanting to have the ability to have those resources available to me. And unfortunately it's only academic institutions that (have access to information), or one book at the public library that people are having access to.

“And it's not really concentrated, it's hidden everywhere, right? And so having a place (for) QT2SBIPOC, having a space that you know that there's authors that are going to reflect pieces of you or maybe have some sort of similar experiences as you. We might both be QT2BIPOC, but we don't have the same experiences.”

dione c haynes, co-organizer of WOKE Comedy, explores the challenges of building queer spaces in Winnipeg.

“I came out somewhere around 2004, and I was going through some pretty severe stuff at my place of employment at the time. I wanted to have a place for other People of Colour who were thinking of coming out, or who were already out to meet. I was hearing a lot of stories for people about bullshit they were dealing with at their workplaces, too. I was just like, I’m gonna do this thing at the Rainbow Resource Centre. And so I had my queer People of Colour discussion group around 2006.

“I was really excited about writing a sex column with Dr. Reece Malone, who at the time was Reece Lagartera. We had a column called Sexpressionism in the local queer rag Swerve and also in Outwords. That was definitely a lot more lighthearted. It was a lot more joyful; answering questions and to some extent be visible in the community as a Black woman, as a Black queer woman. (It was) something I didn’t see as a child growing up, something I didn’t see in this city for sure.

“I really look forward to the day where we have spaces; we have our own restaurants, delis, chicken joints, weed shops, churches, what have you. Whatever it is, people need it. Increasing our autonomy, you know. I would love to own a place where we could put up visiting artists, and not have to worry about paying for a hotel. Actual places that we can be in charge of.

“The situation with buying land and recognizing that we are guests of Treaty 1 … I don’t have all the answers to that navigation, but we definitely have to figure out that if we are staying on this land, what the optimal situation is for figuring out how to work with the original caretakers of this land.”

Callie Lugosi is non-binary and gay as hell. They take photos and manage online content for The Uniter. They look forward to bringing you more accessible queer history.

To learn more, check out Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and People in Western Canada, 1930 - 1985 by Valerie J. Korinek, the University of Manitoba Gay and Lesbian Archives and the Albert McLeod Fonds, previously known as the Two-Spirited Collection.

Published in Volume 73, Number 8 of The Uniter (November 1, 2018)