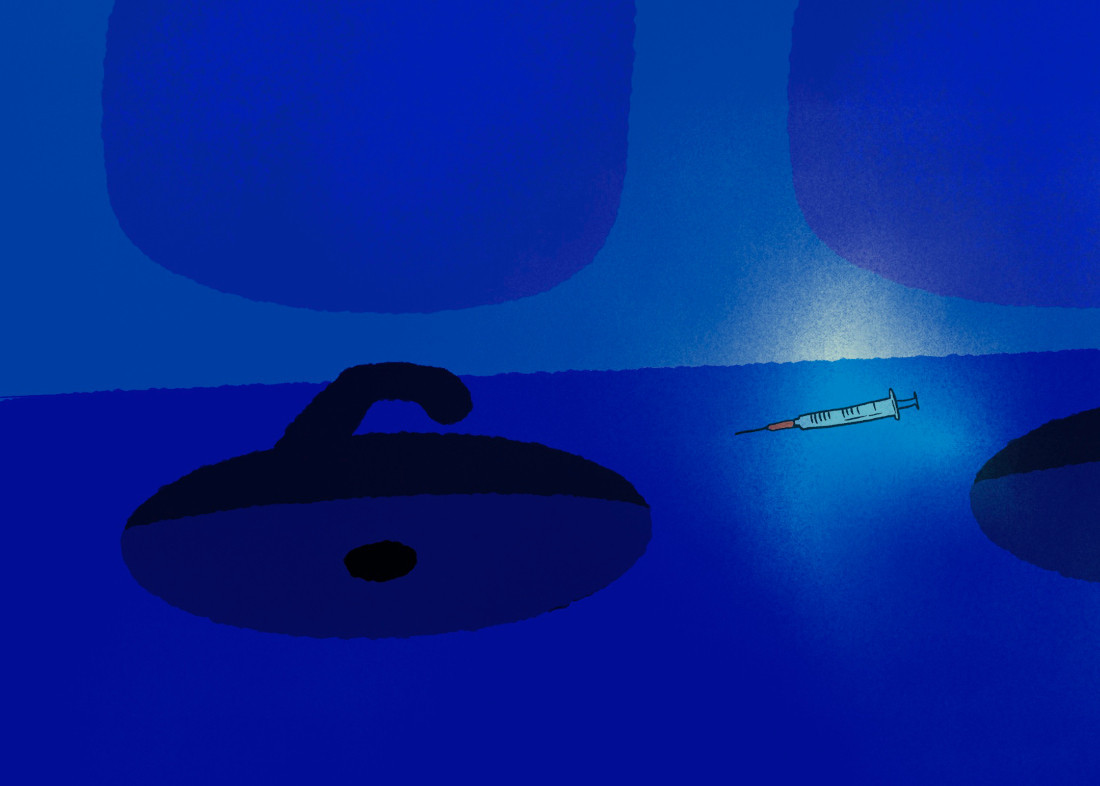

Blue spotlight on the drug-supply crisis

Community advocates call for harm reduction, safe-consumption sites

In Winnipeg’s inner city, and places like Tim Hortons, blue lights in public washrooms are becoming commonplace.

The purpose of these blue lights is to deter people from using intravenous drugs on site, as it’s difficult to find a vein under this type of light. These lights are a response to an increase in overdose deaths in Winnipeg, linked to a heavily toxic drug supply.

Shohan Illsley, executive director of the Manitoba Harm Reduction Network, says studies demonstrate this strategy is ineffective.

“Putting blue lights in your bathroom actually does not deter people from using drugs in your bathroom. People will still use intravenous drugs, and we know it increases their risk,” she says.

Studies demonstrate that blue lights compound the risk of injury or overdose, because they increase the chance a person will miss their vein and inject into the surrounding tissue. Deep-vein injecting is also more dangerous, increasing the potential for infection and deep vein thrombosis.

Illsley also says blue lights may affect visitors with visibility issues or vertigo, who now have an increased risk of falls.

“So not only did you not deter substance use, you also increased risk to all of your patrons who are now using that bathroom.”

‘They just aren’t up for the job’

Sherri Rollins, city councillor for FortRouge, East Fort Garry says she’s heard from constituents about this issue.

Rollins says she’s sat down with business owners who often find it difficult to cope with the amount of people who are using their space almost as a shelter, when they are the only place that is open to the public at night.

Rollins says the deterrent strategy “isn’t ideal, but one is missing the point if they are focused on the blue lights at Tims.”

The City of Winnipeg is missing key primary health and addictions care, she says, due to “a provincial government who won’t come to the table on addictions, mental health and primary healthcare in an effective way like other jurisdictions.”

Rollins says these discrepancies are emblematic of the provincial government’s ideological problems surrounding all healthcare, as well as addictions treatment.

“They just aren’t up to the job. They aren’t doing enough, because they don’t have a harm-reduction focus. They have a recovery focus and an abstinence focus, and that’s why it’s so ideologically problematic,” she says.

Mayor-elect Scott Gillingham’s campaign position was to only go ahead with safe-use sites if the province launched them as part of a broader health approach that included other initiatives and partnered with the City of Winnipeg.

‘Legalize everything yesterday’

Illsley also says blue lights may affect visitors with visibility issues or vertigo, who now have an increased risk of falls.

He says the Province has been “entirely unresponsive and borderline adversarial when it comes to people who are trying approaches different from what they think work.”

“They’ve politicized something that is not a political issue. We see this all the time. It’s not just a conservative thing. We see an inability of all parties in power to work pragmatically and to provide solutions that don’t fit in their ideological agendas.”

Foy says this lack of political will to act is based partly on municipal and provincial electoral systems. Candidates and political parties may also fear that taking stances on controversial issues will lower their chances of (re)election.

“It’s rooted in the fear of losing. No one is actually in politics for the betterment of society. A lot of people go into it well-intentioned, but then you get stuck into environments that aren’t conducive to pragmatism.”

Foy says marginalized people are often driven to use public washroom facilities as a last resort. “They don’t have access to homes often, so they are stigmatized. They often can’t rent. They don’t have access to safe-consumption sites in the city, so they have nowhere to use. So they just have to figure out new ways to do things that increase risk.”

Sunshine House, thanks to a federal exemption under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, is attempting to change that with the first mobile overdose-prevention site in Manitoba’s history.

Sunshine House has launched the 105 to Save Lives Campaign, which hopes to raise $105,000 to continue to fund and upgrade drug-checking machines so people can come in and test their drugs for toxic supply and make informed decisions before using those drugs.

The first of its kind, the mobile overdose-prevention site is set up in a RV and will travel to areas that need harm-reduction services the most around the inner city. People will also be able to have a safe, warm, well-lit place to use intravenous drugs, with peer supervision.

It will be operational on Tuesdays through Sundays. For the last hour of each day in operation, they will travel to low-income neighbourhoods to provide services.

Sarah Guillemard, the provincial minister of mental health and community wellness, said in a recent CBC article that Sunshine House hasn’t followed the proper legal avenues, and “the provinces are responsible for health service delivery, and the Manitoba government was not consulted.”

Guillemard also said that safe-consumption sites haven’t seen reductions in overdose deaths or drug use, and that the province is committed to ensuring a recovery-oriented system. The minister did not provide evidence for the claim when asked to support the assertion.

Shohan Illsley says the evidence for safe consumption sites is clear.

“It will reduce drug-poisoning deaths, respond to overdoses (and recognize) that paramedic services are overwhelmed in this city responding to overdose.”

Illsley says the benefits of these sites extend beyond preventing overdose deaths.

“We also know that safe-consumption services have a 30-block impact on criminal activity and sex work related to substance use. Most importantly, safe-consumption sites give people a safe place to use their substances, so businesses can refer people to the safe-consumption sites instead of washrooms. That’s why it’s disturbing that the Province says there’s no evidence for a safe-consumption site.”

Foy says “We have been sitting on data from the 1990s that indicated everything that we’ve been doing for drug policy in the City of Winnipeg has been backwards and ill-informed from that time, and we just continue to ignore it and try to fit square pegs into round holes.”

“Manitoba last year had 407 deaths from toxic drugs or overdoses, and this year we’re on track to exceed 450. It definitely speaks to a need for a safe-consumption site.”

Foy says the overdose-prevention unit will be staffed with peers, not medical workers, who have expertise in safe substance use. They’ll be able to test if a substance is toxic and have a safe, warm place to inject drugs with someone close by to intervene if something goes wrong.

‘It’s everyone’s responsibility’

“Manitoba last year had 407 deaths from toxic drugs or overdoses, and this year we’re on track to exceed 450. It definitely speaks to a need for a safe-consumption site.”

“We are in an overdose crisis, a toxic drug-supply crisis, and a toxic drug supply is a consequence of the criminalization of substances and the war on drugs.”

Illsey says businesses have a responsibility to the communities they serve.

“If you are so fortunate to have a business in that neighbourhood, you have a social responsibility to those people who live and exist in that very neighborhood. That narrative is really grounded in capitalism and that individualistic narrative that we often hear versus a community-based response”

Illsley points to private-sector coalitions from other jurisdictions like Calgary as something to consider in Winnipeg.

In Calgary, a group called Each + Every, Businesses for Harm Reduction, which “aims to reduce preventable drug-poisoning deaths and help build a more fair and compassionate community by adding the voice of businesses to accelerate drug-policy reform.”

“We know that when we implement harm reduction, some of the harms related to the war on drugs will decrease, such as criminal activity, break-and-enters, things like that,” Illsley says.

Some businesses in Winnipeg are opting for a harm-reduction approach instead of deterrents.

One Sixteen on Sherbrooke, a collaboration between Good Neighbour Brewing Company Taproom and the Two Hands Dining Room, has embraced such an approach.

Kirsten Bernas, director of policy advocacy at West Central Women’s Resource Centre and staff member at One Sixteen, says One Sixteen takes a harm-reduction and anti-oppressive approach, recognizing the risks associated with bathroom use in their space generally.

One Sixteen does not permit the use of illegal drugs in its space. Despite that, taking a harm-reduction approach, it recognizes that people will use substances whether they are illegal or not and may use substances in their washrooms.

“We’ve adopted a washroom-safety procedure that ensures all are welcome to use our washrooms. It also outlines steps staff should take to minimize risk of harm for people using the washrooms,” Bernas says.

This includes doing washroom checks after a certain amount of time, checking with guests to see if they need assistance and calling for the appropriate support when needed.

Bernas says they are developing relationships with Resource Assistance for Youth, Main Street Project and West Central Women’s Resource Centre for support in non-emergency situations. By developing these relationships, no matter what support they need, the staff know who to call.

In that way, it’s not farfetched to call bars and taprooms safe-consumption sites for alcohol. In prohibition, improper methods of making moonshine resulted in toxic-supply issues as well, including “bad moonshine blindness.”

Guillemard’s recent comments surrounding the possible implementation of a supervised consumption site show that, at least in Manitoba’s government, attitudes about illicit substances and those that are legal, are still disparate.

“The strongest harm-reduction strategy is actually to encourage individuals off of the drugs that are harmful. Our message has always been that there is no safe amount of illicit drugs,” Guillemard says.

Illsley, on the other hand, says 70 per cent of people have used an illegally manufactured substance in their life, and most people who use drugs don’t experience harm.

“Harm reduction says if we know people are going to use substances, how can we make that as safe as possible? Substance use itself is not harmful. Eighty to 90 per cent of people who use substances don’t have any harms related to it. It’s everyone’s responsibility to start having nuanced, honest discussions about what substance use looks like in our spaces and how to keep our community safe,” Illsley says.

Ilsley says abstinence and recovery can be part of harm reduction, but harm-reduction principles state that people can still use substances, legal or not. People can still have a good life regardless of the substances they consume.

“Having a better life isn’t dependent on your substance use.”

To learn more about and support the campaigns mentioned in this article, visit:

- 105 to Save Lives, Sunshine House bit.ly/3hw1C6d

- Most needed items, West Central Women’s Resource Centre bit.ly/3G3rccT

Published in Volume 77, Number 09 of The Uniter (November 10, 2022)