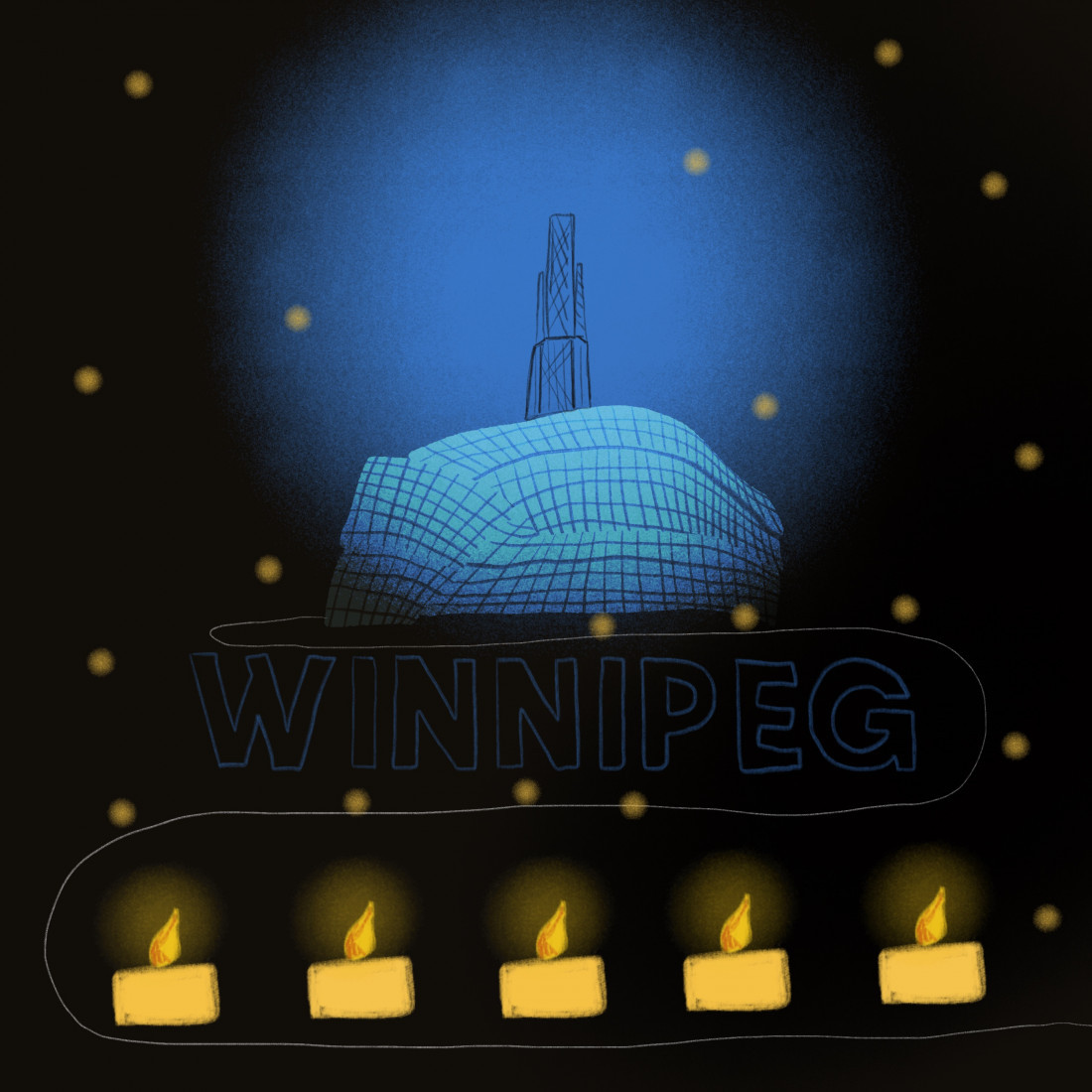

640 electric candles in the wind

City memorializes lives lost due to government laziness with more of the same

Illustration by Talia Steele

From March 11 to 14, around the anniversary of the local arrival of COVID-19, the City of Winnipeg memorialized the 640 Winnipegers who died from the virus by turning off the Winnipeg sign at The Forks. While this memorial took place, the Canadian Museum of Human Rights lit their tower in blue in what they called a tribute to healthcare workers in the city.

I want to be clear that I understand the City of Winnipeg is probably planning on developing a more permanent memorial to those who died of COVID-19, and that this is just a temporary gesture. I also don’t think there is any intentional derision in this gesture on the part of the City or its elected officials. However, it’s hard to ignore how dramatically insubstantial this gesture is relative to the tragedy of over 600 preventable deaths.

It’s especially hard to ignore when a campaign for a memorial garden for police dogs is being treated with greater care and expediency than a memorial for the victims of a pandemic (which is to say nothing of the fact that the memorializing of police dogs is a higher priority than those who have been killed by police, but that’s a subject for another article).

When it comes to public memorials, there are a lot of factors that play into who creates a memorial, who funds it and who is explicitly mourned by it.

There seems to be an apparent ideological reason why governments are quick to memorialize soldiers, police officers who died while employed and police dogs: there is a belief that these lives are the responsibility of the governments that employ them in a way that is distinct from and more honorable than other public employees.

Victims of COVID-19, much like people who die due to poverty or at the hands of police, fall into an odd place in this logic. Their deaths are the direct result of government policy, but many governments do not rush to loudly and publicly memorialize these deaths, perhaps because doing so would be an acknowledgement of their own culpability.

Instead, when deaths at the hands of policy decisions are publicized, it is often the community that gathers to organize public vigils and memorials. These memorials vary widely in their scale and form, ranging from the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt to ghost bikes to smaller stations of flowers, photos and candles.

What rubs me the wrong way about the City’s electric-candle memorial is that it mimics the small-scale and temporary nature of many public memorials with none of the community effort and engagement that often goes into those displays. It was also hosted by the same municipal government that had recently approved a $300,000 memorial for police dogs.

I understand that the City of Winnipeg felt they had to do something on this anniversary, and I understand that municipal memorializing is by its very nature a performative and symbolic act.

However, the hollowness and low effort of turning off a sign and using the money saved on electricity to buy some dollar-store candles makes for an unconvincing performance and the kind of symbolism that suggests the City thinks less of its citizens than dogs. It’s clearly not intentional, and that lack of intention is the problem.

Alex Neufeldt is the city editor of The Uniter.

Published in Volume 75, Number 23 of The Uniter (March 25, 2021)