The 1906 streetcar strike

A people’s history of Winnipeg

A black-and-white photo of a crowd of strikers overturning a streetcar has become one of the most endearing images of the 1919 General Strike. When the event was memorialized with a statue on Winnipeg’s main street, it became one of the signature images associated with the city.

But why a streetcar? Was this a random act of vandalism? That question can be answered by looking at the company that owned and operated streetcars in Winnipeg and the 1906 streetcar strike.

Like most cities in the early 20th century, Winnipeg’s streetcar system was dominated by a private monopoly, the Winnipeg Electric Company (WEC).

The WEC achieved its first franchise for streetcars in 1892 and had a monopoly on gas, electric and public transit in Winnipeg by 1900. With its monopoly power, the company proved incredibly lucrative with earnings increasing 30 per cent a year through the early 1900s.

The WEC’s power resulted in price-gouging so bad that even Winnipeg’s commercial elites were unhappy. In order to protect their bottom lines, Winnipeg’s elite pushed the city to create Winnipeg Hydro to compete with the WEC. Winnipeg Hydro opened its first plants in 1911.

Winnipeg’s working class also had significant grievances with the WEC. Fares were seen as being too high for an inadequate level of services while wages for streetcar operators was low. All of this boiled over during the streetcar strike in 1906.

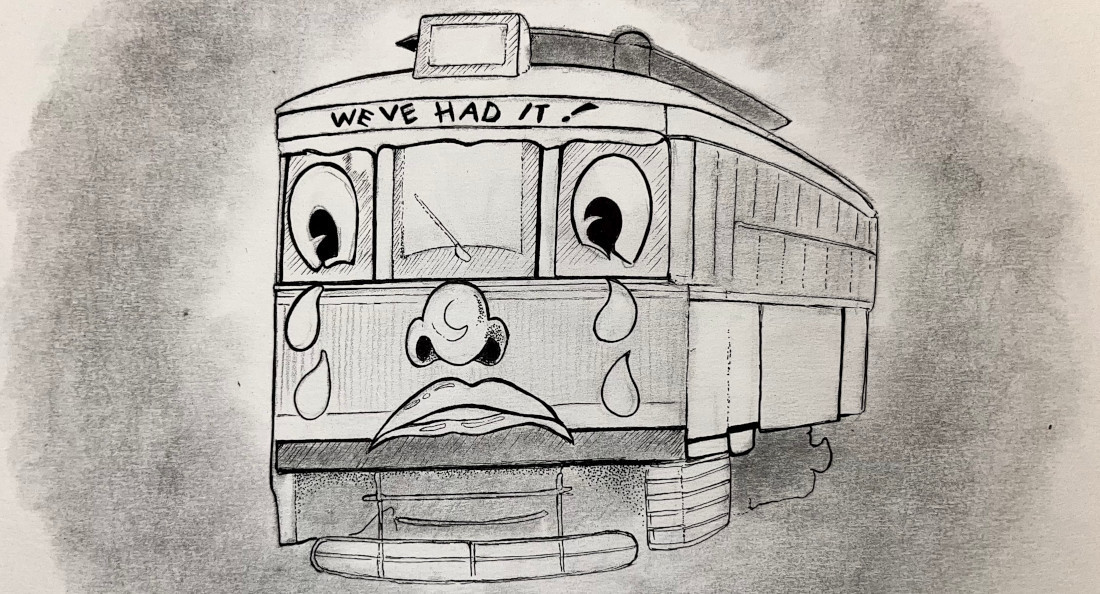

Winnipeg’s first streetcar strike began March 30, 1906 over low wages and horrible working conditions. Drivers were exposed to the elements, and the braking system required brute force to stop a streetcar. Wages and working conditions were the primary concern for the workers, but palpable anger around the WEC fueled a wider boycott campaign and widespread vandalism.

The vandalism started almost immediately. Streetcars were toppled by crowds of people, their cables cut, their windows smashed. With the vandalism also came threats of violence against the scabs operating the streetcars, with some of these operators being chased by crowds.

Much of the property damage and violence came from strike sympathizers rather than strikers, which demonstrates the underlying anger many felt towards the WEC.

In the North End, streetcars were empty or service was stopped altogether. The slogan of the boycott was “we walk.” Many trudged through muddy and snowy Winnipeg sidewalks to show solidarity with the strikers.

At the request of WEC, the provincial magistrate swore in “special police officers” and strike breakers, recruited from a private security force, to operate the streetcars and protect WEC property. These strike-breakers made the situation worse by beating both strikers and strike sympathizers.

As the violence escalated, mayor Thomas Sharpe called in troops from the Royal Canadian Mounted Rifles to quell the unrest. Even then, crowds of people still destroyed streetcars in full view of the troops. It wasn’t until Sharpe ordered the troops to load their weapons that the crowd stopped.

The parallels of the 1906 streetcar strike and the 1919 General Strike are many: widespread class anger and solidarity, monopoly capitalist price gouging and the use of force to repress strikes.

These parallels demonstrate that how cities were constructed and who benefited – as well as issues like collective bargaining, working conditions and union recognition – majorly influenced workers in Winnipeg.

Connecting the dots between the streetcar strike and the General Strike provides the colour to fill in that famous black-and-white photo.

Scott Price is a labour historian and program director at CKUW 95.9 FM.

Published in Volume 78, Number 10 of The Uniter (November 16, 2023)