Stability could help cure my insomnia

Sleep isn’t for the weak. It’s for the unburdened.

I woke up this morning before sunrise, feeling well-rested and ready to start my day. It’s a rare experience.

In a three-part series for The New Yorker that ran during the summer of 2015, Maria Konnikova noted that researchers agree “our average sleep duration on work nights has decreased by an hour and a half” over the past five decades, and 69 per cent of people “report insufficient sleep.”

One expert found that children had “lost nearly a minute of sleep a year.” I’m not a parent or a sleep scientist, so I can’t tell you why this might be the case. However, I know that my sleep has suffered for years. I feel groggy more days than not, and it’s a struggle to get out of bed, especially during the winter.

Researchers interviewed for Konnikova’s series attribute our collective sleep deprivation to different genetic, social and environmental factors. One thing disrupting sleep patterns is how much time we spend staring at screens, particularly close to bedtime.

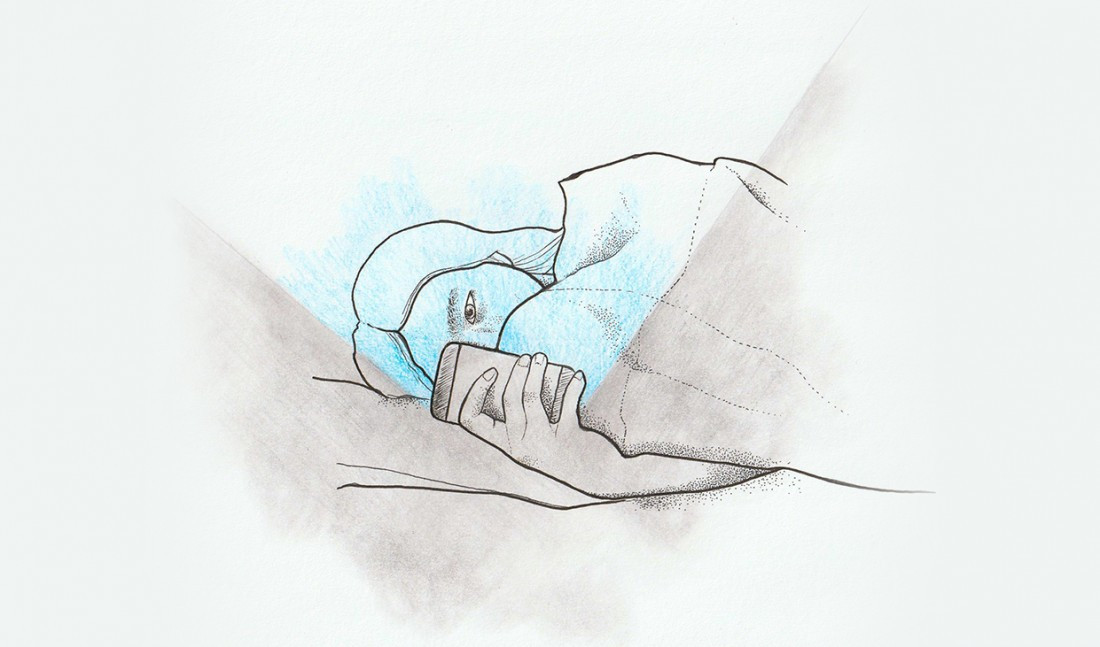

“When we spend time with a blue-light-emitting device (such as a smartphone or laptop), we are, in essence, postponing the signal to our brain that tells it that it’s time to go to sleep,” the first part of the series reads. What it fails to note is that, sometimes, round-the-clock attachments to our devices are necessary.

Capitalist society prioritizes productivity over personal wellness. That’s especially evident now, when some non-essential businesses are forcing their employees to work, even when it increases their chances of contracting and spreading the new coronavirus.

Many people who freelance, work from home or hold multiple jobs need to be online or on call throughout the day. Folks actively seeking out work rely on computers and social media to apply for positions, reach out to potential clients and update their resumes. Even people in more stable positions always feel pressured to be “on” and always working.

For some of us, it’s simply not possible to separate ourselves from our phones and laptops. Everything I do for both of my jobs occurs online, and I often spend my “free” time researching, checking work emails and typing out my ideas.

I know taking my phone to bed – or spending all day staring at a computer screen only to do the same thing during and after dinner – damages my health. But I can’t afford to stop.

This frustrates me to no end, as does a tweet I saw circulating earlier this year. In it, a user who has now changed their privacy settings writes: “I feel like my generation lost hobbies. Everything doesn’t have to be a hustle, side hustle or money-making enterprise. Sometimes, it’s just fun to do something because it brings you joy, peace, relaxation or allows you to be creative. Let’s rediscover hobbies in 2020.”

While I absolutely support the idea of doing things purely for enjoyment, the reality is that many folks don’t have that option. Many of us need to monetize our favourite activities to simply get by.

A few years ago, someone asked me what I did for fun, and I said I work at The Uniter. That’s true, but my job as an editor is crucial to my survival. I’d love to get more sleep, take up a hobby and close my laptop every so often – but those are privileges I can’t always afford.

Danielle Doiron is a writer, editor and marketer based in Winnipeg. She can’t eat wheat right now, so if you have any killer gluten-free recipes, send ’em over.

Published in Volume 74, Number 23 of The Uniter (March 26, 2020)