Sports, sponsors and cold hard cash

What is at the end of the money trail?

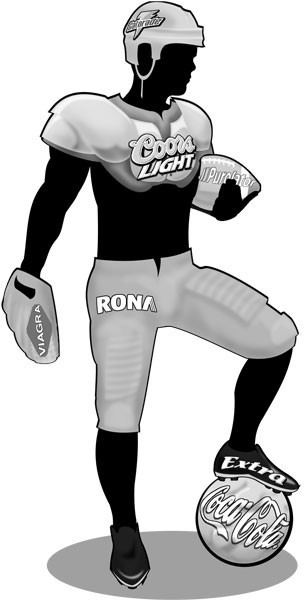

AC/DC sang that “money talks” and when it comes to professional sports, money talks big. In Canada and the United States, the NHL alone has 17 major corporate partners. That’s just for the league, not to mention the individual advertising contracts that the teams and players have signed.

Just look at the Super Bowl, the NFL’s crown event, which was estimated to have over 160 million viewers. That accounts for over a third of America’s estimated adult consumer base.

Many of those viewers (26.9 per cent) responded to a BIGresearch survey for the Retail Advertising and Marketing Association, saying that the commercials are the biggest highlight of the game.

Even our Canadian league, the CFL, lists Purolator, Scotiabank, Celebrex and Nissan as league sponsors. Individual teams have other marketing partners, such as RONA Home and Garden which supports the Winnipeg Blue Bombers.

The Bombers alone have 15 major sponsors (who in return receive logos on their website), and an additional 506 sponsors at all other levels.

Advertising is a powerful advantage for both the teams and the companies. The exchange of ad space gets messages out to consumers about the benefits of using products that are associated with the leagues, teams and players.

Players aren’t left out of the money circle, selling spaces on their body for big money. Tiger Woods grossed the highest estimated earnings for endorsements at $100 million in 2007. Basketball’s LeBron James pulled in an estimated $25 million that year, only a little less than Woods’ fellow golfer Phil Mickelson, who earned an estimated $47 million.

James said almost two years ago that his goal was to become the first billionaire athlete. Getting drafted straight out of high school and signing a cool $90 million contract with Nike wasn’t a bad start, and neither was the $80 million contract extension with the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2006.

After taking notes from the wealth guru Warren Buffett, James has made significant financial decisions, including releasing his agent and forming several companies to handle his financial affairs; all managed by Maverick Carter, a childhood friend of James.

But when tracing the money back to its source, we always end up at the company. No matter which athlete, team or league is endorsing the product and wearing the logo, they are still getting their money from that company.

That is the power behind sponsorship for the business world. In exchange for cash and product, they gain publicity, tax write-offs and a classier image. But companies need to be wary, too.

They don’t like to gain negative publicity if they can help it – whether it’s because of an unfavourable sports incident (how many Michael Vick sponsors still hang around him?) or a losing season. Other things, like season-ending injuries can have bad images, too (where are Tom Brady’s commercials?).

Businesses aren’t the only ones with something at stake, either. Sport in general is largely divided by dollars. Amateur and minor league athletes don’t have access to the kinds of resources (or salaries) that major sports and leagues can offer their players and support staff.

People want to be like their idols and businesses know that. If to be like their idols means people have to buy something their idols endorse, then that product will fly off the shelves.

Published in Volume 63, Number 19 of The Uniter (February 5, 2009)