Overdose training sessions assist in harm reduction

Manitoba Harm Reduction Network addresses stigma surrounding substance abuse

"We all know and love people that use drugs,” Veda Koncan, project coordinator at the Manitoba Harm Reduction Network (MHRN), says. Nov. 12-18 was Substance Use Awareness Week in Manitoba, and this year, the campaign focused on the stigma surrounding substance use.

“Drugs that are used by people who are marginalized or societally disadvantaged tend to have more stigma stigma," Koncan says.

These drugs usually include opiates. Drugs used more often by people with privilege, such as pot and ecstasy, have less of a reputation.

Koncan explains that the MHRN changed the name of the week from “Addictions Awareness Week,” to centre the ways in which substance use is normal and not inherently harmful.

The MHRN offers harm reduction training at their 60 locations around the province, many of which dispense naloxone. Street Connections, one of the sites, hands out about 15 kits every month.

Naloxone, sold under the name Narcan, is a drug capable of temporarily reversing the effects of opioids, which makes it possible to stop an overdose.

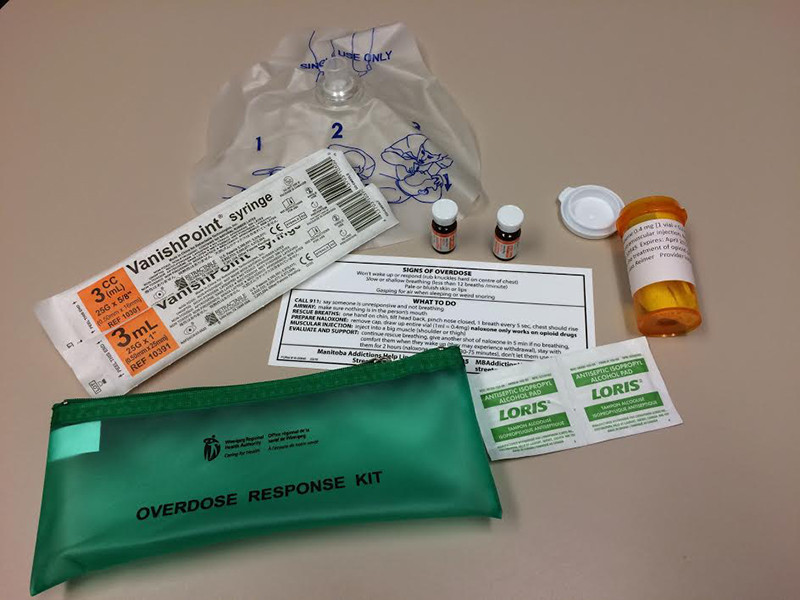

Contents of a standard kit.

“Anyone who is at risk of opioid overdose is eligible for a free take-home naloxone kit,” Shelley Marshall, clinical nurse specialist at the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (WRHA), says.

Manitoba has a problem with carfentanil, an opioid 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Non-opioid drugs are being cut with fentanyl/carfentanil, which puts users at risk of an overdose even if they do not believe they are taking opioids.

Marshall explains that anyone who uses substances is at risk, due to the prevalence of fentanyl/carfentanil. Because of this, training can be helpful to anyone who will be taking, or be around, people taking drugs.

The MHRN hosted their first public training session on Nov. 22. Participants learned how to recognize an overdose and respond accordingly, Koncan says. They also learned how to tell the difference between an opioid overdose and one provoked by other drugs. Naloxone kits were available.

“When (Street Connections, previously only a needle-exchange program) opened up to distributing naloxone, we saw a much broader population of people who use drugs, including suburban folks,” Marshall says.

The WRHA has a nurse provide naloxone training at addiction program meetings, where people are at risk of overdose after leaving the program, because their tolerance will be low. Marshall believes such targeted training is beneficial, but this information typically doesn’t reach the general public.

While naloxone training can save lives, there are some barriers. Marshall explains that a lack of funding and human resources means that not all dispensing sites offer the training to the public.

As well, people using drugs regularly do not always have the patience required to listen to 20 minutes of instructions before receiving a kit.

“You really cannot give away an injectable medication without training somebody on how to appropriately use it,” Marshall says.

The naloxone distribution program launched in January, but publicity is an issue. Marshall believes some communities do not know of the availability of naloxone.

According to Koncan, a few harm-reduction tips that may be helpful include taking a smaller dose of a new substance, knowing CPR, using a less direct route, not using alone and knowing the signs of an overdose.

“If you’re planning on using, get naloxone,” Marshall says, adding that none of the distribution sites are very busy, and that’s what they’re there for.

For more information on harm reduction, visit gov.mb.ca/fentanyl. Locations of naloxone distributors can be found at streetconnections.ca.

Published in Volume 72, Number 11 of The Uniter (November 23, 2017)