Origin Stories: Bîstyek

Forbidden colours

For Kurdish visual artist Bîstyek, colour has always been a symbol of resistance. A prolific painter, his practice grew to incorporate sculpture, design and public art, recognized on a national scale.

“I come from a culture that’s very colourful,” he says.

Born in Syria, his family faced persecution for celebrating Nowruz (Persian New Year), which commemorates the spring equinox.

“It’s a day where we dance, we eat, we celebrate,” he says. “The police would arrive and start to arrest people. They would tear down our flags. They took our colours away.”

As a child, he remembers getting into trouble over a drawing assignment. “I just used three markers: green, red and yellow.” Upon handing it to his teacher, he was slapped in the face.

“I had no idea what I did,” he says.

His friend clarified the issue after class, pointing to the colours of Kurdistan. “Are you stupid? It’s a flag!” his friend said. Bîstyek cites this as a turning point in his life. “That’s when I knew I was Kurdish.”

In the midst of cultural oppression, watching cartoons sustained his relationship to colour. Images of warmth and peace provided an escape.

“We did not have a TV, so I would go to my cousin or my neighbour’s house to watch,” Bîstyek says. Upon arriving home, he would recreate the characters in his sketchbook. “Then at night, when I really felt like watching cartoons, I would just look at my drawings.”

Fleeing the Syrian civil war, his family took refuge in Lebanon. Seven years later, they were admitted into Canada.

Bîstyek eventually quit his job at a Winnipeg coffee shop to focus exclusively on art. He quickly gained the support of local curators and gallery owners, leading to his first exhibition in 2020.

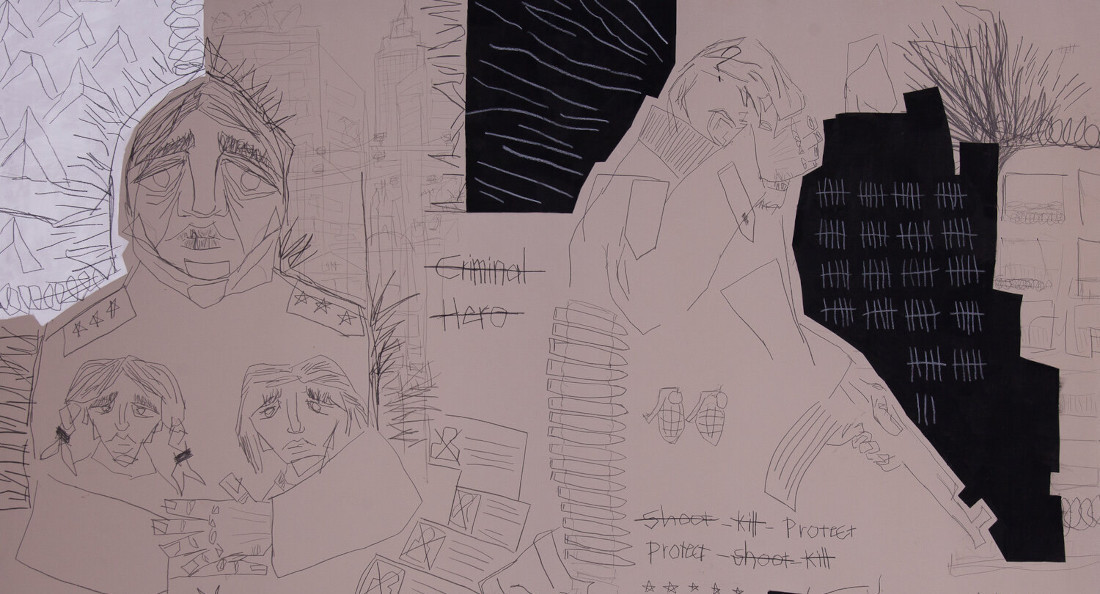

Now a professional artist, his paintings retain the same bold lines, primary colours and childlike essence of his early work. For Bîstyek, the innocence of youth is always in tension with the violent realities of conflict.

“It’s an artist’s responsibility to reflect the times,” he says. “To ignore what is happening around me, I don’t feel like I am fulfilling my duties.”

He is interested in how art captures the emotional experience of a time and place. For him, it is an act of remembering. “It’s not just my story, it’s a lot of people’s story,” he says.

“I come from a city called Afrin, where olive trees are very important. I remember asking my mom, ‘Who planted these trees?’ She replied: ‘Your ancestors did.’”

It astonished him how the actions of individuals hundreds of years ago would eventually feed and shelter his community. “The work we do today will pay off tomorrow,” he says, “even if not for you, then for someone else.”

His latest work is a series of smaller, more intimate portraits – a departure from the large canvases, political scenery and pop-culture iconography he is known for. “I started (my career) with faces,” he says. “Looking at someone’s face is a mirror to what they’re feeling inside.”

He is adamant about breaking free from the ways he has been labelled. “There are more sides to who I am. I am not just a refugee.”

Despite this, Bîstyek is heartfelt about the trajectory of his career, which began with monochrome drawings and has now blossomed into intensely colourful canvases. “The work is evolving,” he says. “This is what I’ll be doing for the rest of my life.”

Published in Volume 78, Number 23 of The Uniter (March 28, 2024)