Live forever or die trying

The Pantages Playhouse is the last window to Winnipeg’s Vaudeville past

When the City of Winnipeg announced in 2018 that it was selling the Pantages Playhouse Theatre, it wasn’t the first time that the fate of an iconic local building was left to the whims of developers. But unlike the old airport or arena, which were neither the first or last of their kind in Winnipeg, the Pantages is the last irreplaceable remnant of an era that shaped the city into what it is today.

Winnipeg’s status as a cultural hub for music, dance and drama has its roots in the vaudeville era of live theatre. An art form that flourished from the 1880s to the 1930s, vaudeville defined pop culture until it was eventually supplanted by radio and talking pictures.

Winnipeg was a major stop on the vaudeville touring circuits, with many of the biggest stars of their day playing here, as well as performers who would later go on to become major stars.

A show you could bring your parents to

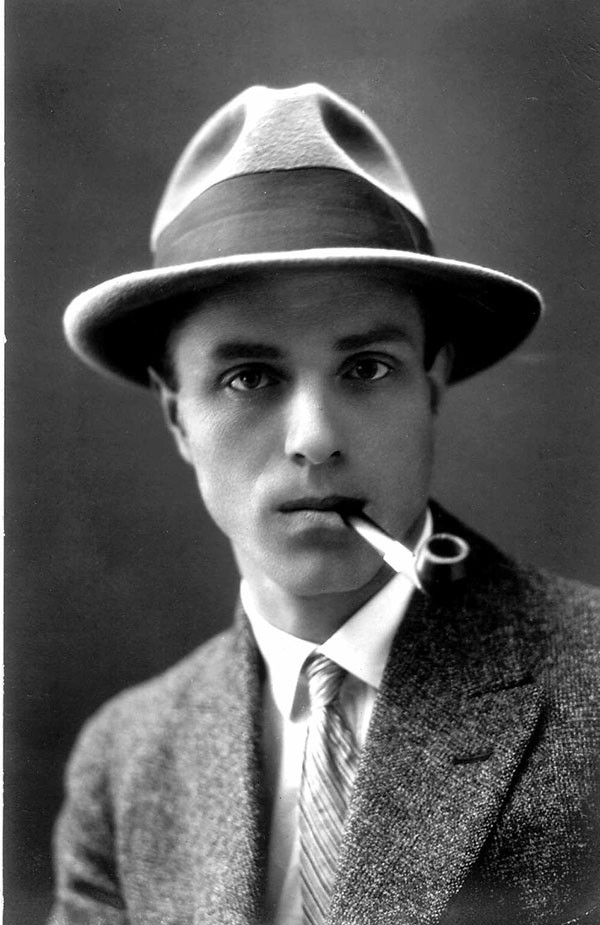

Grant Simpson, vaudeville actor // Supplied image

Grant Simpson is a musician, composer and producer specializing in vaudeville-style performance. He performed with and co-owned the Frantic Follies vaudeville show in Whitehorse for nearly 40 years before moving to Winnipeg in October. Simpson defines vaudeville as “a variety show.”

“Variety theatre has been around since the early 1800s,” Simpson says. “But in the 1880s, (theatre impresario) Tony Pastor began using the term ‘vaudeville.’ Before (Pastor), it was primarily a male-oriented audience. He was the first to include families, women and children in his audiences. The idea of vaudeville was that it was so clean that a child could take their parents to a show without fear of embarrassment.”

Many of the theatres in which vaudeville was performed were chains: theatres in multiple cities throughout the US and Canada owned by the same company, who would book acts to travel from one theatre to the next.

One such chain was the Pantages. Founded by Alexander Pantages, who opened the first Pantages Theatre in Seattle in 1904, the chain arrived in Winnipeg with the 1914 construction of the theatre on Market Avenue. Winnipeg then became the first stop of the Pantages circuit, with the final stop in

Los Angeles.

The Pantages was far from Winnipeg’s only major vaudeville house. Competing chain Orpheum already had a theatre on Fort Street by 1911, while the first of Winnipeg’s two Strand theatres opened in 1912. The Dominion, Bijou and Walker theatres had all been in operation since the previous decade, while the Princess Opera House, Grand Opera House and Winnipeg Theatre had entertained the city in the 1880s and ’90s.

On any given day in the 1910s, Winnipeggers could see Buster Keaton at the Pantages, the Marx Brothers at the Orpheum, a production of British playwright W. Somerset Maugham’s Manitoba-set play The Land of Promise at the Winnipeg Theatre or the Winnipeg Political Equality League’s production of How the Vote was Won at the Walker, each for well under

a dollar.

Winnipeg o’ My Heart

While the headliners were typically out-of-town acts making tour stops, some Winnipeg artists did manage to make a name for themselves through the vaudeville circuit.

One example is Marjorie White, who began her onstage career singing and dancing in 1908 at the age of four. She toured with the children’s troupe “The Winnipeg Kiddies” until 1921, when she and American actress Thelma White (no relation) formed the comedy duo “The White Sisters.”

She eventually signed a deal with Fox Film (later Twentieth Century Fox). Her first screen role was as the star of 1929’s Happy Days, the first feature film shot and released entirely in widescreen. She made 15 movies in Hollywood, including with major directors Mervyn LeRoy and Raoul Walsh, before dying in a car accident in 1935.

However, for Winnipeg performers who weren’t hitting the road on vaudeville tours, there was also a vibrant local drama scene. Winnipeg’s earliest dramatic companies in the 1870s and ’80s mostly brought in performers from out of town and were subject to public scrutiny due to the treatment of their actors. A lawsuit by actress Nellie Fillmore revealed that theatre owner Dan Rogers forced women performers to coerce male patrons into buying drinks after shows, fining actresses who left before he gave them permission to do so.

But the arrival of Harriet “Hattie” Anderson (spouse of C.P. Walker) in Winnipeg drastically changed the theatrical landscape of the city. Anderson began writing theatre criticism under the pseudonym “Rosa Sub” in the weekly newsletter Town Topics.

Her writing redefined public perception of theatre in Winnipeg as a respectable activity for women, both as audience members and performers. She went on to produce live plays, musicals and comedies in Winnipeg, laying the groundwork for organizations like the Women’s Musical Club of Winnipeg and for performers like Helen Bokovski to flourish.

"I don't like vaudeville, but it likes me"

Greater representation for women in theatre in the vaudeville era was part of broader cultural trends of the time, with first-wave feminism in full swing. It’s something Grant Simpson encountered in conversation when people would invoke old jokes mocking vaudeville dancers.

“They’d always reference (dancers) not being very smart,” he said. “That wasn’t my experience.”

“I thought, ‘I guess dancers used to be way different than they are now?’ So I started to study, and it was totally not that way. I learned how much editors bashed (women performers) unfairly. A lot of these dancers were empowered, astute businesswomen managing huge careers and extended families while touring. But they were bashed in the press because of the misogynistic paradigm of the 1800s.”

Simpson’s time in the Yukon also led to him studying “Klondike Kate” Rockwell, a notorious Dawson City performer, who in the 1890s had a chaotic love affair with a pre-theatre chain Alexander Pantages. At the time, while Rockwell was a theatrical professional, Pantages was a struggling bartender.

Pantages “married a violin player in one of his shows behind (Rockwell’s) back and really screwed her over,” Simpson says. “She ended up taking him to court and getting a lot of money.”

Variety Lights

Vaudeville stages were diverse among ethnic lines as well. While plenty of objectionable material still made its way in front of audiences (blackface and other pre-vaudeville forms of racist caricature continued well into this era), vaudeville stages showcased performers from Black, Yiddish and other forms of traditional theatre together for the first time.

Winnipeggers saw acclaimed Performers of Colour like Aida Overton Walker or Jue Quon Tai on the Orpheum or Pantages stages. Audiences were hungry for entertainment that reflected the diversity of early-20th century life, and conversations about representation were hashed out on and around the vaudeville stage.

On the week of Jan. 11, 1915, a husband-and-wife duo performing under the name Mr. and Mrs. Robyns took to the Pantages stage performing their comedic play, David Berg, or 100 Cents on the Dollar. The play’s title character was Jewish, and the Robyns were aware of the long history of Jewish stage characters being depicted as racist caricatures.

Wanting to ensure that their portrayal was respectful to Winnipeg’s Jewish audiences, the Robyns corresponded with a number of American rabbis who consulted with the couple. The Winnipeg Tribune printed the letters on Jan. 9, 1915, in which Minneapolis rabbi Samual Deinard praised their “refreshing” depiction of “my own idea of the Jew – difficult though I find it to convince non-Jews of it – is that he is just a human being with all the faults and all the virtues that other human beings may be possessed of.”

Local performers made similar strides toward representation on Winnipeg stages. Comedian Noah Witman graced Winnipeg stages before making the transition to local radio and, eventually, television. In 1954, he started a weekly Yiddish radio show, which was credited with keeping the language alive in Winnipeg.

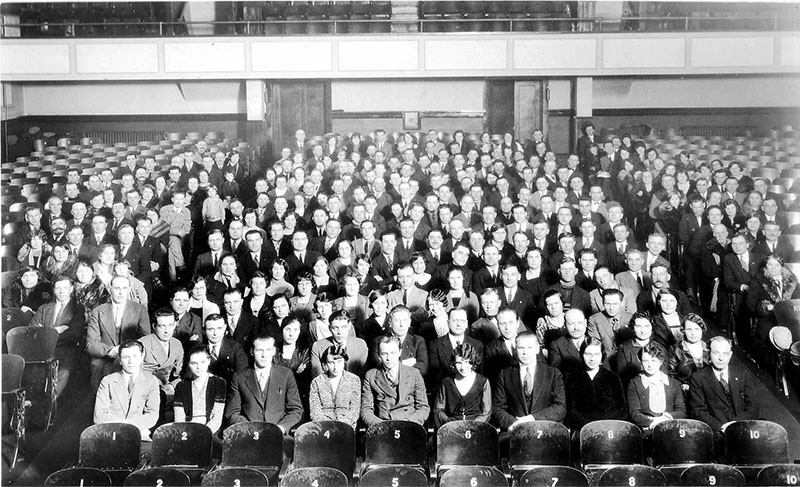

Auditorium of Ukrainian Labour Temple (upper gallery not visible), in Winnipeg, c. 1928

Winnipeg’s diasporic Ukrainian community also kept their theatrical traditions alive with local performances, but historian Orest Martynowych says it took longer for their performances to be shown in proper theatres.

“The first (Ukrainian) plays (c. 1904 to 1911) were staged in church basements and community halls,” Martynowych says.

“By (1911 or 12) several permanent, well-organized dramatic and choral societies had emerged. As they grew in strength and popularity, and tackled increasingly ambitious stage projects, the new drama societies abandoned the church basements and ramshackle halls on the side streets of the North End and began to perform in real theatres on Main Street and Selkirk Avenue.”

Martynowych says early Ukrainian productions in Winnipeg were mostly of classic plays from Ukraine, but as the scene developed and flourished, local performers and playwrights emerged. He points to husband-and-wife actors Matthew Popovich and Liza Sladkaya, playwright Semen Kowbel and “especially” playwright Myroslav Irchan.

Playwright Myroslav Irchan, in Winnipeg, around 1925

Irchan “wrote with compassion and insight about the oppressed and downtrodden,” Martynowych says. He points to a 1929 article in a conservative Toronto newspaper, which referred to the leftist Irchan as “the most popular and influential author in the country,” despite the fact that he wrote exclusively in Ukrainian.

Stage to screen

While the vaudeville scene in Winnipeg faded away with those of other cities, the performers and comedy styles pioneered on vaudeville stages never went away.

“The way I describe it, the vaudeville industry collapsed with the Depression, the war and the advent of TV and radio,” Grant Simpson says. “People could stay home and get the same variety of entertainment through their radio. Nobody had money, so that was a good answer for people who couldn’t afford to go to the theatre.

“It really was just a method of getting entertainment to the people. Radio and TV was a more effective way (of doing so). The vaudeville industry changed into the movie and radio industry.”

Famous performers made that same transition. Bob Hope, Jack Benny and the Marx Brothers are among the many performers who graced Winnipeg’s vaudeville stages before making the move to films and TV.

Many remembered the city fondly. Hope claimed to have golfed in Winnipeg for the first time (a sport he became so passionate about that he wrote an entire memoir about it), and Marx quipped in the first chapter of his 1959 autobiography, “I don’t know anything about cooking. On those frequent occasions when my current cook storms out, shouting, ‘You know what you can do with your kitchen!’ only the fact that I have a fairly good supply of pemmican left over from my last trip to Winnipeg saves me from starvation.”

”Things ain’t what they used to be, and never were”

But Winnipeg’s theatres weren’t as lucky. All but the Pantages were permanently converted into movie houses. The Winnipeg Theatre, Orpheum, Dominion and Bijou were all either demolished or burned down in 1926, ’48, ’57 and ’79, respectively.

The Walker became the Odeon movie theatre in 1945. It finally reopened as a live performance venue in 1991, changing its name to the Burton Cummings Theatre in 2002 and was bought by Jets owners True North Sports & Entertainment in 2014. Only the Pantages remains intact in all its turn-of-the-century splendour.

That is, until the City announced that the theatre was up for sale. The City purchased the theatre in 1923, renaming it the Pantages Playhouse. It was sold to a new owner in 1943, but the City seized it again two years later for tax reasons.

It’s unclear why, after nearly 75 consecutive years of City ownership, councillors on the property and development committee felt the need to sell the theatre for $530,000 (a fraction of the more than $8 million in public money Winnipeg awards to True North annually).

According to the Winnipeg Free Press, the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra operated the theatre from 2011 to ’18 at no cost to the city, and only after the WSO offered to buy the theatre did city hall consider selling the Pantages to the highest bidder.

Those bidders were development partners Alex Boersma and Lars Nicholson. While the duo insists they want to keep the Pantages in operation as a theatre, some have expressed concern that the City declined to sign a development agreement with Boersma and Nicholson, which would require them to hold true to that promise. So as it stands, the future of the Pantages is still in limbo.

But the spirit of the vaudeville performances it once housed is still alive, whether in the present-day performances of Grant Simpson, or in the big-name entertainers still working in vaudeville formats.

“Take someone like Stephen Colbert,” Simpson says, “a real political commentator. In the vaudeville era, we had (political satirist) Will Rogers, who was saying some powerful stuff on behalf of First Nations treatment. (Rogers was an outspoken member of the Cherokee Nation.) That political aspect we see in today’s comedy world was in vaudeville.

“There’s an argument to be made that if the vaudeville industry was still alive, we’d have people like Colbert as headliners. So it wouldn’t really change that much.”

Grant Simpson will host a talk at the Winnipeg Public Library titled Greasepaint on the Prairies: The Story of Vaudeville in Winnipeg on Saturday, March 30 at 2 p.m. Register at wpl.winnipeg.ca or 204-986-6450.

Published in Volume 73, Number 22 of The Uniter (March 21, 2019)