Diamond development

U of W physicist develops diamond-based particle detector

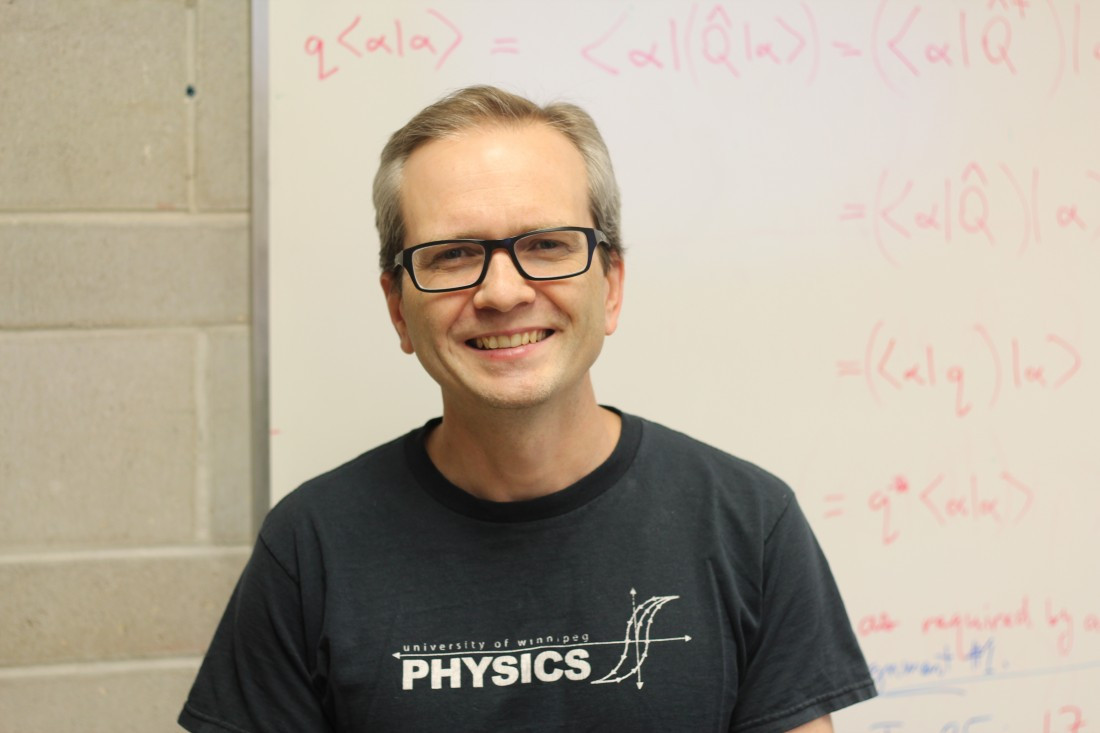

The possibility of being involved in a groundbreaking experiment is what attracts many physicists to their field. This is certainly true for University of Winnipeg (U of W) physics professor Dr. Jeff Martin.

Martin and his team developed a particle detector that uses synthetic diamonds grown in a lab. It is the first detector of its kind used in a particle physics experiment, which was conducted at the Jefferson Lab in Newport News, VA. The innovative results earned publication in the prestigious physics journal Physical Review X.

“That’s my motivation when I do an experiment, I want to discover something totally new, and I want to have that opportunity for physics students here as well,” Martin says.

Researchers at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Geneva, Switzerland attempted to use diamond-based detectors to discover new particles but gave up because the technology was too new.

Martin and his collaborators from University of Manitoba and American institutions were willing to experiment with technology that was not fully mature.

“We needed something that would sense the radioactive particles, but not die when exposed to large amounts of radiation,” he says.

They adopted the technology that researchers at the LHC had invented, and then took it to the next level by actually using it in an experiment.

Martin sees the potential for diamond detectors to be used in the future. The research is important for other fields that need detectors or electronics that can survive in intense radiation.

Diamonds have a very high thermal capacity. Because of this, the research could be used in medical imaging, or to detect radiation in space, and it could open up new uses of diamonds in such things as computers.

“Maybe we will one day have all our computers made not of silicon, but diamond instead,” he says.

Martin’s project is an example of how the U of W can be at the forefront of physics research.

“Even a smaller university like the U of W can have people involved in big physics projects and thinking of those big science questions, the kind of questions that you answer with these kinds of experiments,” he says.

Two U of W students who have since graduated played a large role in the study. Both were undergraduate students working at summer jobs in the physics lab.

For Doug Storey – now a graduate student at University of Victoria – working on this project has set him on the career path that he is on today.

“I could tell it was something big right from the start. My role in the project was to help develop the diamond electron detector. This meant we were taking diamonds, coating them in gold, and then hooking them up to electronics to study how they behaved and how we could transform this into useful technology for the experiment,” Storey says.

It’s a fitting time for the experiment results to be released as students are applying for summer lab jobs. One of those summer jobs could involve being part of the next groundbreaking experiment.

Martin and three other U of W physicists are now leading a major experiment searching for the neutron’s electric dipole moment. Physicists from Canada and Japan are collaborating on the project.

Published in Volume 70, Number 22 of The Uniter (March 3, 2016)