Beauty in the slow decay

Artist combines passions for plants, photography and computers in Momentary Vitality

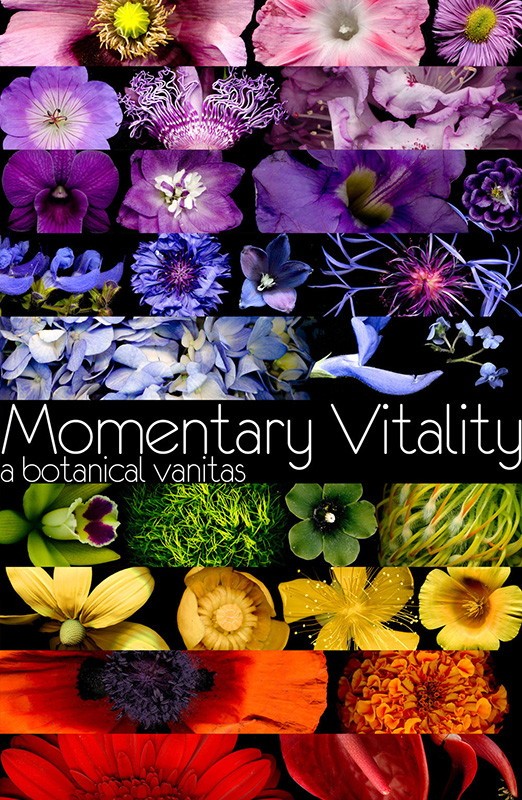

Despite conjuring up images of kitsch-crafters arranging dried petals on paper at the kitchen table, “flower art” remains the simplest description of 21-year-old University of Winnipeg German studies student Joel Penner’s latest project, Momentary Vitality, which is anything but vapid and pastoral.

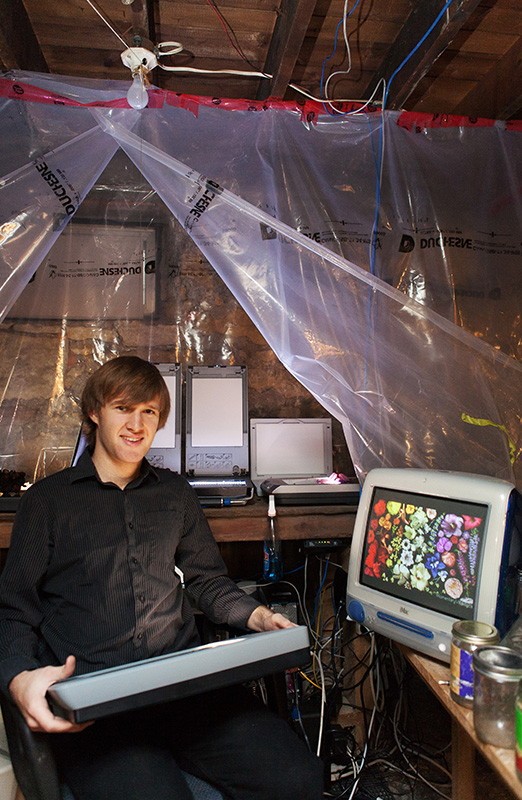

After visiting his flower processing and editing lair, which resembles a mad-plant-biologist-gone-hacker’s science lab, The Uniter sat down to talk about Penner’s art project, cosmic unity and science.

The Uniter: Typically, flower fancy is the domain of plant biologists or hobbyist gardeners, but you seem as fascinated as any of them by the beauty of flowers. How did your interest in flowers or plants in general develop, and what proportions has your own botany taken?

Joel Penner: I’ve loved plants for as long as I can remember, but usually just in terms of cultivating them indoors. I really can’t explain where this fascination came from. I’ve always been entranced by the simple fact that they’re alive. That fascination has then taken different forms as I’ve matured. I started getting into photography and videography in my early teens.

After a few years of simply taking photos with a conventional camera, I began taking photos with scanners and experimenting with normal time-lapse photography. So this project grew out of the fusion of those hobbies coupled with my longtime fascination with computers. Other manifestations that my love of plants has taken have been the planting and maintaining of a garden of native prairie flowers and grasses, and experimenting with hydroponics and grow lights.

I understand your project involves flowers and video. Can you describe the project and the concept on which it is based?

For Momentary Vitality, I take cut flowers and foliage and put them on ordinary computer scanners to have them scanned multiple times an hour. Each flower takes anywhere from a week to four to fully dry out. After that process is done I compile the images into time-lapse videos. I then make videos to music or ambient nature soundscapes that try to show the wild beauty of the various contortions and unexpected movements that play themselves out in the footage.

I also try to make the sequences tell the “story of the universe.” Just like ourselves, each flower is made up of elements that were synthesized via nuclear reactions that occurred in the cores of stars billions of years ago. I think this is one of the most amazing scientific facts, as it points to the idea of a cosmic unity of which we’re all a part. As I develop the project, I want to make more sequences based off of this idea, but also off of other scientific aspects of the flowers such as their evolutionary history, geographical origins, and mathematics underpinnings.

How far along is the project, and what sorts of media will the project involve?

Although I technically started this project four years ago, I began in earnest in the spring of 2011. I’d say I’m about a quarter done. So far it’s taken the form of seven short films, multiple posters and a feature in a few botanical and art shows. If the next phases with the (National Film Board of Canada) are approved, we’re planning on (at this point) making a movie, interactive iPad app and an exhibit. I expect it to be completed in either 2013 or 2014.

“ Just like ourselves, each flower is made up of elements that were synthesized via nuclear reactions that occurred in the cores of stars billions of years ago. I think this is one of the most amazing scientific facts, as it points to the idea of a cosmic unity of which we’re all a part.

Joel Penner, artist

What do you hope the viewers/users get of this out of this project?

I hope that my love of the beauty of the world around us wears off on them, and that it inspires them to become more fascinated with the beautiful universe that we are a part of. Moreover, I hope that it sparks, or furthers in them, an interest in the wonderful botanical worlds that inhabit our sidewalk cracks, constitute our rainforests, and make possible our dinner plates. On the other hand I want to share how photography has opened my eyes to the world around us, which sometimes seems mundane. For example, some of the best specimens I got from this past summer were from a common weed, Western Salsify. I came to love how its seed pod puffs out into a sphere, ready to be blown into the wind like the seeds of a dandelion. It shows that there are things happening outside of our habituated paradigms that are worth becoming curious over.

The project is being funded by the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), correct? How has the application process been, and what are the challenges of building such a partnership?

Partly correct. The NFB works by having applicants going through three stages - a brainstorming phase, a phase where a sample of that idea is created, and the final production phase. This past summer I completed the first phase and am hoping to move on to the next two.

As an artist, from what/whom do you draw your strongest inspiration?

A lot of the inspiration for this project has come from the non-vocal movies Koyaanisqatsi and Baraka. Their simple ambient videography shows our world and global civilization in stunning ways. In terms of how the project highlights the theme of mortality, I draw inspiration from the Hellenistic Stoic philosophers, who wrote much about the subject.

Do you see your project as chiefly classical or modern in form, or both? The project combines nature with technology, and art with science. How do you perceive these relationships within art?

I see it as both classical and modern. As a species we like separating knowledge into different areas, and sometimes they don’t interact as much as they should. Reality in and of itself simply is, a fact we can hardly comprehend given our relatively meagre minds and senses. I’m trying to blur the boundary that traditionally blurs art and science to show how they can actually go hand-in-hand. The boundary blurring goes further. Our intimate relationship with plants is one that’s endured since time immemorial.

As I develop my ideas, I hope to show this relationship that cultures around the world have had with plants, and what this means.

See Penner’s kaleidoscopic botanical video and photos at www.momentaryvitality.ca.

Published in Volume 67, Number 8 of The Uniter (October 24, 2012)