A sacrifice of Olympic proportions

Toll taken on athletes’ bodies should start to be addressed by IOC, fans

The Vancouver 2010 Olympics, for some, is a distant memory. For others, the bruises splotched across tattered bodies are only just beginning to fade.

Though Canadians remember these Olympics as a celebration of national (hockey) pride, the rest of the world will remember Vancouver 2010 as the Olympics that killed Georgian luge athlete Nodar Kumaritashvili. His death was both untimely and tragic, but not surprising.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has official values of developing a better world through sport. As an organization committed to ethical standards, they support humanitarian and diplomatic work. Yet, other than sport-specific rules on padding and safety devices, provisions are not made for the lifelong health and well-being of Olympic athletes.

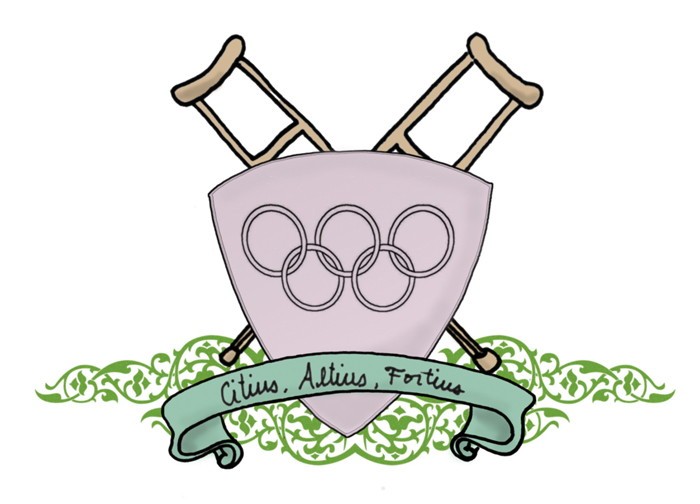

The IOC’s ethics may pay lip service to safety, but these seem overridden by the age-old Olympic motto of Citius, Altius, Fortius (Latin for “Faster, Higher, Stronger”). The competitors know it is about pushing limits, and they are sacrificing their bodies and, as Kumaritashvili proved, their lives.

Consider the health of Canada’s top athletes. Maëlle Ricker won snowboard cross gold, but did so after her ninth knee surgery. Ashleigh McIvor brought home ski cross gold despite having dislocated her shoulder 14–15 times (by her count). Women’s hockey legend Hayley Wickenheiser played with a broken bone in her right hand during the 2006 Olympics. In 1997 and 1998, injuries caused Clara Hughes to miss nearly two entire seasons.

As any competitive athlete knows, injury is inevitable.

We, the audience, are willing to accept these risks in exchange for a contribution to national pride. For varying reasons, the athletes are willing to accept these risks as well. It is time that we collectively acknowledge the reality of the dangers of pushing the limits, both in the present and the future.

The luge track was deliberately built to be the fastest in the world. Were Olympians denied the ability to challenge world records due to track design, the outcry from athletes, officials and fans alike would have been thundering.

Does this quest for glory warrant sending sliders 150 km/h down a track, or skiers 115 km/h down a hill?

This may be the reality of sport, but another reality is that five of our alpine skiers had their Olympic dreams dashed by injury after devoting years of their lives training for the event. If we can finally see the error in our logic, perhaps their hard work, and Kumaritashvili’s death, will not be in vain.

Despite the lip-service safety and peripheral padding at the Olympics, the overriding ethic truly is that of “faster, higher, stronger.” These athletes are striving for one moment of podium glory, regardless of whether concussion-induced brain damage will rob them of that memory a decade later. These days, our athletes are not ambassadors, but martyrs.

We must ask what we want of ourselves and our athletes for the Sochi, Russia Olympics in 2014. Perhaps we should ask the Olympians of 20 years ago where they are now.

Can they make a living? And more importantly, can they still walk?

Alana Westwood is an evening-and-weekend philosopher whose blog can be found at http://gapingwhole.wordpress.com

Published in Volume 64, Number 23 of The Uniter (March 18, 2010)