The changing nature of education

Coming to terms with the market

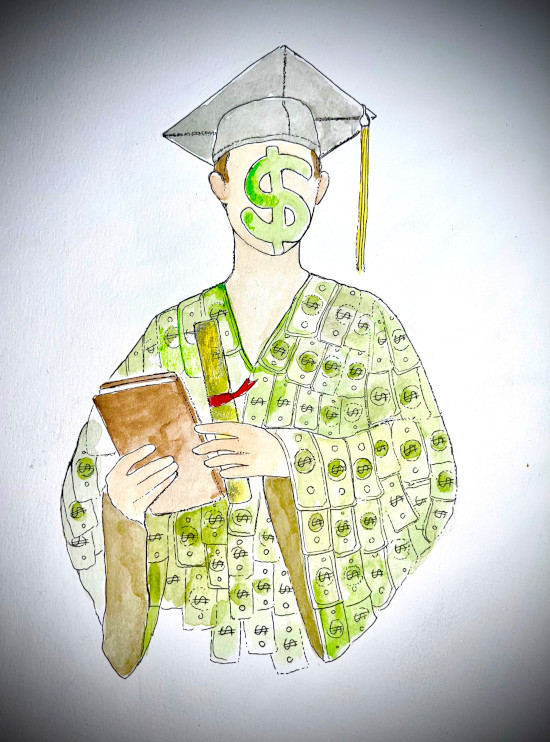

Illustration by Gabrielle Funk

Every year, the University of Winnipeg (U of W) welcomes more than a thousand new students. For students, starting university can signify a new chapter filled with glee. For institutions, these are fresh minds to educate.

However, there has been a noticeable shift for the worse in the campus zeitgeist regarding this once mutually beneficial exchange.

According to publicly available data published by the U of W, the student body has shrunk over the last few years, down to around 8,945 in 2022 and reaching a peak of 9,670 in 2019. To most, this might seem like a non-issue. For the university, however, it presents a great concern: revenue.

Although nominally an institution of higher learning, the university is perhaps much better understood as a vessel of economic activity. Hundreds of staff members are employed. Businesses can thrive in a locale with thousands of prime-aged consumers within their reach. Students earn credentials that can help them access better job opportunities.

It seems like a perfect deal for everyone involved. Yet this social contract necessarily depends upon two things: the demand for the university’s services and the supply of students.

Despite the fact that total enrollment numbers have steadily declined, the share of international students has rapidly increased within just a few years.

In 2018, international students made up roughly nine per cent of the student body. In 2022, that number almost doubled to nearly 17 per cent. This is no coincidence and is a part of a much broader trend seen across Canada.

Accommodating foreign students is part of a strategy universities employ to combat declining revenues. Depending on the course of study, international students can be expected to pay up to three and a half times what domestic students pay.

Total enrollment may decline, but so long as international-student populations increase, institutions like the U of W might not only break even but actually record a surplus. In exchange, international students are presented with opportunities for permanent residency, higher real incomes and living standards that are among the highest worldwide.

But everything has its downsides. Permanent residency is not a guarantee, and international students have some of the highest rates of underemployment once they graduate.

A sudden influx of international students may also strain deeply needed resources, like campus housing and nearby rentals. Conse- quently, this raises housing costs for everyone involved. The deal might not seem like the bargain it was hailed to be.

Attracting students for fiscal reasons only further subordinates education to the all-consuming invisible hand. Yet it is foolish to pretend as though one should not pay attention to the demands of the market. Goods and services are not made out of thin air, and the university cannot operate without paying attention to its bottom line.

Fortunately, universities can learn from existing alternate models. In many European countries, there are no tuition fees. There, education is treated as a public good and not like a pre-packaged commodity, all while maintaining academic standards that rival, and in some cases surpass, that of Canadians.

Gabriel Louër is a volunteer contributor for The Uniter. He serves as emerging leaders director for the UWSA.

Published in Volume 78, Number 17 of The Uniter (February 8, 2024)