Untangling science from colonialism

‘Trying to decolonize the classroom’ at the U of W

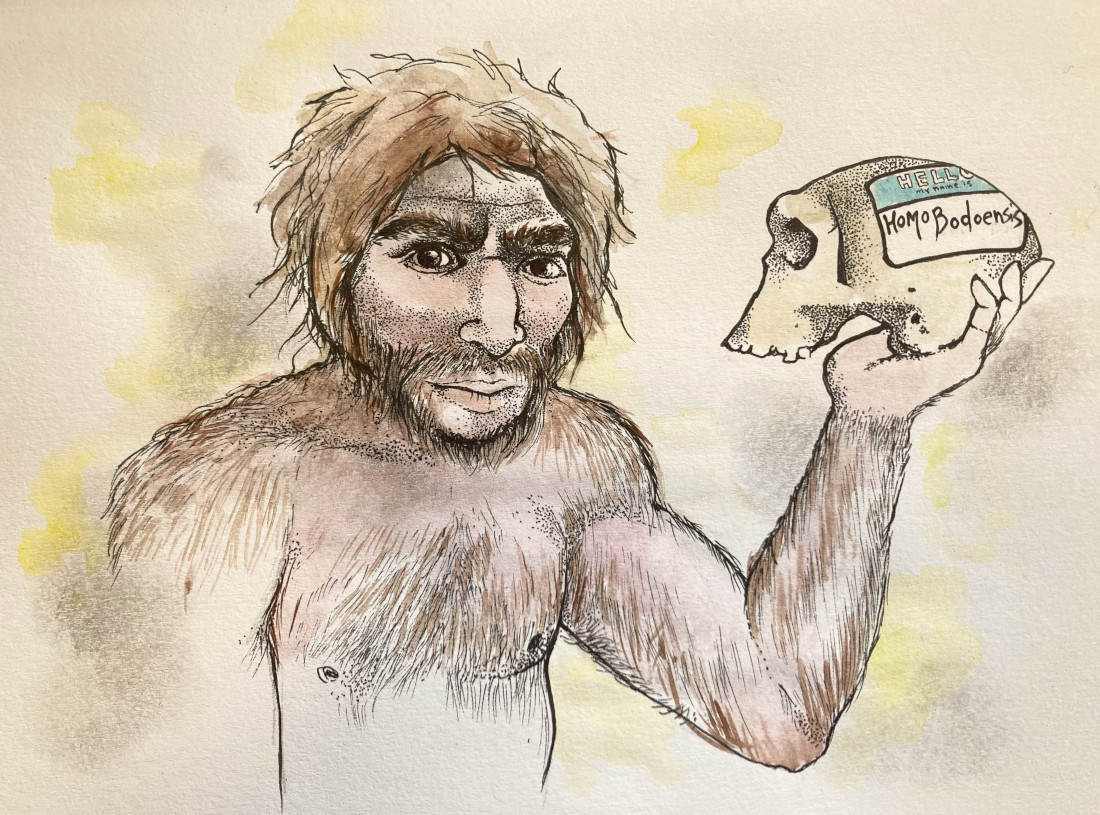

Illustration by Gabrielle Funk

“They were brainy. They produced really fancy tools,” she says, “(like) hand axes that are really difficult to make. I tried making one, and mine didn’t look like anything, I can tell you that.”

To be fair, that was only her first attempt.

The University of Winning (U of W) paleoanthropologist led a team of international researchers to discover and rename one of our direct ancestors, previously thought to be either Homo rhodesiensis or Homo heidelbergensis.

Not only have these names created confusion among scientists, as DNA evidence has suggested that some species thought to be Homo heidelbergensis are actually Neanderthals, but the name Homo rhodesiensis honours racist and colonizer Cecil Rhodes.

“Cecil Rhodes was one of the most atrocious colonial monsters in South Africa,” Roksandic says. “It’s really unfortunate, because you’re calling an African specimen by a very unpleasant name. I tried to use that name, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it.”

So she and her team began to look into renaming the species.

Homo bodoenis is an umbrella term that will make talking about species previously known as Homo rhodesiensis and Homo heidelbergensis easier for paleoanthropologists.

The name Bodoensis comes from a 600,000-year-old fossil specimen called Bodo cranium discovered in Ethiopia in 1976.

“At least when I say Bodoensis, I associate that with Africa and not with Cecil Rhodes,” Roksandic says.

She admits that, in the past, paleoanthropologists have not always been open to listening to local people about their history and culture.

“It used to be common for foreign researchers to just go places and not consult local knowledge-bearers,” she says. “If you don’t include their knowledge, well then you’re just perpetuating your own ideas and ideology.”

Chris Wiebe, a U of W chemistry professor, is trying to decolonize the classroom with the Indigenizing Chemistry at the University of Winnipeg grant.

While some might think of science as unbiased and impartial, Wiebe points out there are many ways scientists can consciously and unconsciously perpetuate racism and colonialism in the classroom.

He points out that white researchers may be given unconscious preference for grants, or that papers being reviewed from Western universities may have better chances of being published.

Indigenizing Chemistry will bring in members of the Indigenous science community to discuss changing curricula, encouraging more Indigenous students to take more science courses and how the U of W can attract and hire more Indigenous faculty members.

“We can’t decolonize chemistry with mostly white settlers in our department,” Wiebe says.

The grant will also bring in local highschool students, so they can see what successful Indigenous scientists, like Jaime Cidro, look like in action.

“With this grant ... we’re not trying to solve (colonialism). We are trying to take the first step to figure out what these problems are and make our classrooms safe spaces for BIPOC and women,” Wiebe says.

Published in Volume 76, Number 10 of The Uniter (November 18, 2021)