Turbulent takeoffs

Unsettling revelations and air travel

Over the past couple of years, I have come to the conclusion that flying is the worst way to travel.

Beyond the environmental concerns, the actual process of flying is extremely uncomfortable: arriving hours ahead of time, going through the tedious security process and then being loaded onto sardine-sized seats. It sometimes feels like it’s all an experiment to test the limits of human patience.

Admittedly, part of my distaste for air travel emanates from my own anxieties. As takeoff and landing commence, my blood pressure spikes, and my seat fills with sweat as I enter what feels like a direct confrontation with my own mortality. I know that, statistically, flying is less risky than driving, but the lack of control and a childhood of watching Mayday makes it feel like an unstable mode of transport.

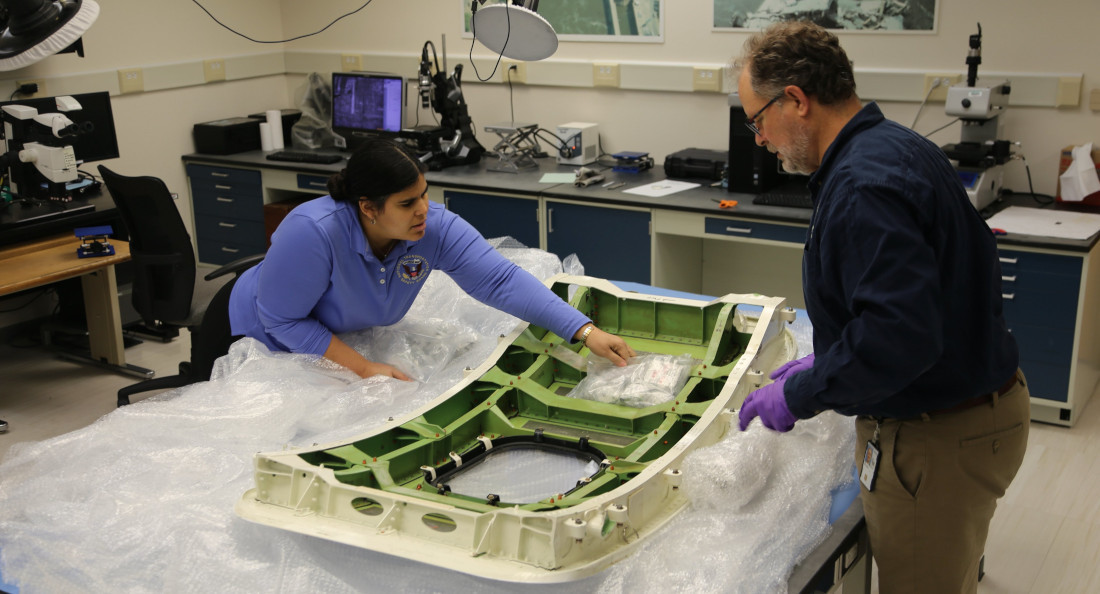

My fear of flying has only been amplified with the news of a turbulent takeoff on an Alaska Airlines flight from Portland to Southern California. As the plane was halfway to its cruising altitude, going more than 600 km/h, an improperly secured piece of the plane blew out. The cabin air contorted seat supports, ripped off headrests and exposed passengers to the thousands of metres between them and the ground.

Fortunately, there were no fatalities, and the only things lost were clothing, phones and a sense of security. The unsettling part of the whole situation is that it is not a completely random occurrence.

Boeing, the manufacturer of the 737 Max 9, made itself the leading name in the aerospace industry off the back of innovation and quality constructions. But, over the past five years, Boeing has come under fire for declining quality control. In 2018 and 2019, two high-profile crashes of Boeing 737 Max 8s killed 346 and resulted in the fleet of 387 aircraft being grounded.

A United States Federal Aviation Administration investigation found that Boeing had repeatedly dismissed concerns regarding safety issues and prioritized deadlines and budgets over security.

Since their merger with McDonnell Douglas in 1997, Boeing has had near-monopoly power in the aviation industry, with the only sizable rival being Airbus.

With this power, Boeing has made sizable cuts to their workforce, reduced compensation and chosen offshore work to avoid unionization. These labour issues are at the core of the devolution of Boeing’s quality control and only signal more issues into the future.

Terrifyingly, Ed Pierson, former manager at Boeing planes and quality-control whistleblower, claims he will never fly on newer Boeing planes including the 737 Max.

The revelation that Boeing has been repeatedly choosing to prioritize profits over the safety of human lives is horrifying for any flight-phobic individual like myself. The idea that safety is in the hands of corporate executives who have minimal regard for human life will only make me grip the armrests that much harder during takeoff and landing.

For Winnipeggers, the lack of alternatives means efficient intercity travel largely hinges on aviation. The options seem slim: hope that regulatory agencies can force Boeing to improve quality control, give up on air travel or push for investment in rail and bus travel.

Reflecting on these options is daunting. As I learn more about the grip that corporate profits have on the aviation industry, it only makes flight seem so much more turbulent.

Patrick Harney is the comments editor at The Uniter. He’s awful to sit beside on a flight.

Published in Volume 78, Number 16 of The Uniter (February 1, 2024)