True crime is still true life

Local producers respond to demand for real-life stories of tragedy

A cacophony of sirens blares from rescue ve- hicles as they whip past a traffic clog. Drivers tense up and look around. What happened? Is it serious? Did someone die?

In a 2017 NBC News article titled “The Science Behind Why We Can’t Look Away From Tragedy,” journalist Danielle Page writes that witnessing violence and destruction “gives us the opportunity to confront our fears of death, pain, despair, degradation and annihilation while still feeling some level of safety.”

Having eyes glued to someone else’s horrible moment from the relative safety of a car is not unlike turning on a true-crime podcast for entertainment. The observer is detached from the reality of the narrative, yet the sense of “this could have been me” is palpable – maybe even thrilling.

True crime, a genre of reality-based storytelling, turns real-life crime and murder cases into a form of entertainment – and this can raise ethical concerns.

“True crime tells the stories of people who have been victims of trauma, who’ve experienced trauma, who’ve perpetrated trauma, who’ve been impacted by trauma,” Dr. Steven Kohm says. Kohm is a criminal-justice professor whose research at the University of Winnipeg focuses on popular criminology, crime films and society.

Unlike witnessing a murder firsthand, true crime can be viewed as a detached form of entertainment. “It’s inevitably about commercializing trauma,” he says.

An actor and crew member on the set of one of Farpoint Films’ several true-crime shows. - Farpoint Films (Supplied)

The recent rise of true-crime television

True crime has had a remarkable uptick in popularity in recent years. According to Triton Digital’s Canada Podcast Ranker, half of Canada’s top 10 podcasts consumed in December 2023 were true crime. In 2022, the Toronto Star reported that Canada was the fourth-leading country for true-crime obsession, topping the United States at number five.

Two Winnipeg-based production companies, Farpoint Films and Black Watch En- tertainment, added true crime to their roster in recent years due to demand from streaming services like Super Channel (Canada) and True Crime Network (US).

Farpoint began producing true crime in 2017 despite attempts to avoid it altogether. “It just got to the point where we couldn’t ignore it. There was just too much demand,” Farpoint Films producer Scott R. Leary says.

Farpoint has produced more than 200 hours of true-crime content to date. The company produces several true-crime shows for Super Channel, including Cruise Ship Killers and Death of the Party.

Leary is familiar with his viewership and what attracts people to true crime.

“The average viewer watches true crime with the intent of ‘I’m glad I’m not that per- son’ but also ‘I would never let that happen to me.’ And so it’s a very base sort of detachment from that perspective,” he says.

Farpoint signed a deal last year with Super Channel in Canada to produce 150 hours of true-crime television. “There’s a worldwide market for all of this stuff,” he says of their Canadian, US (True Crime Network) and UK (A+E Crime+Investigation) viewership.

“Not one country prefers true crime over another country. They all seem to really like it,” Leary says.

Andrew Malabre, showrunner for Finally Caught produced by Black Watch Entertainment, traces true-crime popularity back to the days of Dateline (1992 to present) and 20/20 (1978 to present). “They were there (back then), but the fact that they have their own channels, you know that there is a market for it now,” Malabre says.

While both Farpoint and Black Watch are Canadian production companies, most of their stories come from the US and elsewhere due to access to freedom-of-information requests, Leary says.

“The vast majority (of our stories) are in the US. Certain states are easier to work with than others. Michigan, Texas, Florida, it’s quite easy to get freedom-of-information requests and to get stories back from their police departments, from the DAs, so that’s where we focus.”

“We do want to cover Canadian crimes. We just need willing participants,” Malabre says.

A crew member views the monitor on the set of a Farpoint Films true-crime show. - Farpoint Films (Supplied)

A brief history of violence as entertainment

So who are these true-crime junkies driving up the market demand?

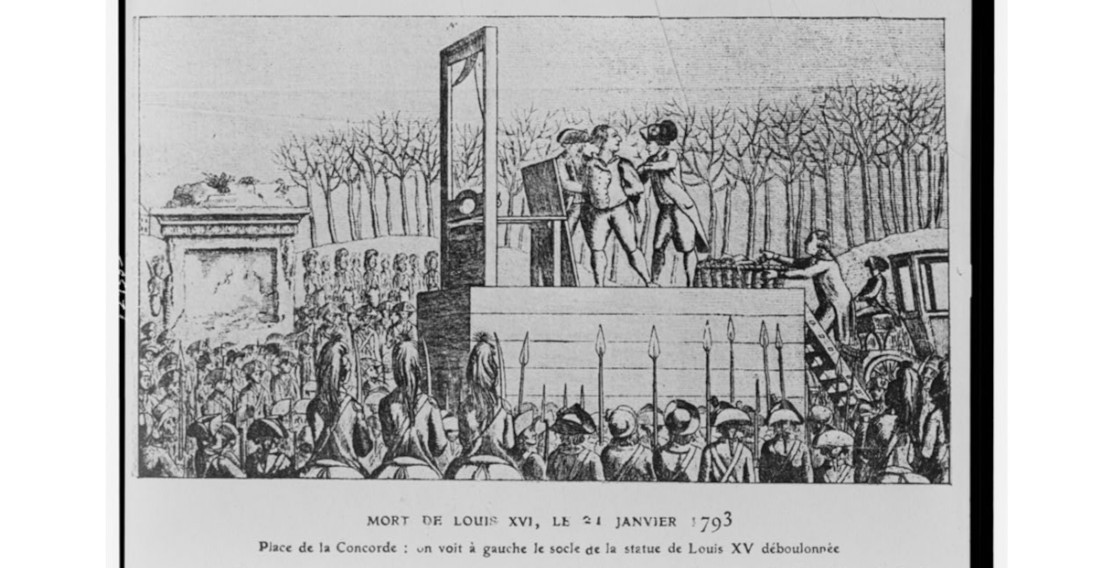

Kohm says true-crime lovers today are not unlike our ancestors going “back hundreds of years.”

“Punishment used to be a very public thing. People would go to the town square and watch people being executed or pillaried. People were entertained by it, and that’s nothing new,” he says.

In 17th-century England, reveling crowds would gather at public executions to join the court of popular opinion. Adults and children alike would throw flowers to celebrated criminals, jeer at executioners and hurl in- sults at loathed perpetrators.

Kohm says people’s desire to see criminals discovered, rooted out and punished for crime is part of the “civilizing process” that has been repressed.

“People are interested in crime and punishment because they’re simple moral tales that tell us something about what is good and bad – which actions are deemed good and worthy and which are not,” he says. “So I think crime is the perfect example for our culture to really think about these bigger questions.”

Meanwhile, in 18th-century France, the Reign of Terror brought thousands of “guilty” anti-revolutionary individuals to be guillotined in what is now Place de la Concorde in Paris. There was entertainment, food, souve- nir stands and programs listing the lineup of those getting their heads chopped off.

“So (now) punishment happens behind closed doors, and violence becomes the exclusive domain of the government,” Kohm says of the current punitive process. “People are interested in watching or hearing or reading about true crime because it connects with something that has been kind of sublimated over time.”

Scott R. Leary is a producer at Farpoint Films. (Supplied)

True crime on the brain

A rise in true-crime consumption has psychologists talking about its impact on mental health. Dr. Chivonna Childs, a psychologist with Cleveland Clinic, studies this subject.

In a 2023 article for Newsroom titled “How True Crime Can Impact Your Mental Health,” Childs says true crime “can increase our anxiety because we become hypervigilant.”

Individuals run the risk of having their worldviews change if they’re “constantly consuming grisly murder stories,” she says.

Studies show women are the largest consumers of true crime overall, a phenomenon supported by psychologist Dr. Scott A. Bonn in an article for Psychology Today.

Women’s fascination with true crime is driven by empathy, Bonn says. “Female fans identify with and can easily imagine themselves in the role of the victim.”

Meghan Duffy, executive producer at Black Watch Entertainment, agrees. “When I’m working on true crime, I think ‘oh my goodness, what if this happened to me?’” Duffy says. “Just naturally as a woman I think that.”

According to Duffy, Finally Caught is “skewed more female.”

“It is predominantly females who watch true crime, and that’s great, because I think for a lot of the cases that we cover, women are victims,” she says, mentioning that she often thinks about what she would do if found in similar situations.

Ethical concerns in true crime

About to launch its third and fourth seasons, Finally Caught has garnered attention for its “commitment to victims’ families” and a nomination for Seasons 1 and 2 for Best Episodic Series at the 2023 CLUE Awards at Crimecon, according to a recent press release.

“We are not looking to sensationalize or glorify the murderer in any sense. If anything, we’re giving the victim’s family a spotlight and a platform to talk and share their story,” Duffy says, whose background in journalism informs this approach to storytelling.

“We pick stories and shows that will help us with that mandate in mind always,” she says. “We do not want to retraumatize anyone. If the family doesn’t want to be involved in this story, then we don’t cover those cases.”

Production companies can claim to be on the side of the victim. However, Kohm cautions that, despite their best intentions, “there’s always that ethical dilemma that you are essentially leveraging someone else’s trauma for your own gain.”

At the end of the day, crime is the tragedy that brings the families, producers and viewers together. Without the crime, there is no story.

“I don’t think they can have clean hands, necessarily, in terms of not being part of the machinery that’s commodifying trauma,” Kolm says. “And also, as audiences, we’re complicit, too. I mean, we’re watching it, too.”

Supplied photo

Farpoint Films (Supplied)

The upswing to true crime

There are upsides to telling true-crime stories – and these are attributes for which Black Watch’s focus is recognized.

Malabre says true-crime shows offer a venue for families to express grief and remember their loved ones.

“Yes, it is television, but if we do it properly, we can celebrate the life of the victim,” he says, adding that a lot of the victims’ families will often thank them for the show’s handling of their loss.

“It can dredge up a lot of painful memories,” Leary says, “but it can also have that moment of being able to get that story back out into the public so that their loved ones aren’t just forgotten.”

Duffy says true crime also provides consumers a sense of control over their greatest fears by learning how to avoid bad situations.

“The thing with true crime is that we don’t have to sensationalize anything,” she says. “They’re getting murdered. That’s scary. That lends itself naturally to a specific audience that’s wanting to empower themselves and wanting to inform themselves.”

Kohm also says distraction from the daily horrors of modern life is another draw.

“What a bewildering world we live in when even serial killing can become an enjoyable product that we can sit down in our leisure time to enjoy,” Kohm says, who ac- knowledges that his entire career is built off of “the pain and suffering of people who’ve been victimized.”

Whatever side of the argument one lands, true crime is first and foremost a commodity for entertainment.

“We’re filmmakers, we’re storytellers, we’re journalists, and we’re using our art to create shows that people are watching,” Duffy says, whose team strives to uphold the highest standards of journalism to avoid sensationalizing trauma.

Leary says, “I’m never going to say that it’s important for people to watch true crime. What I’m gonna say is, if you enjoy watching true crime, then keep watching it.”

“At the end of the day, while they are true stories and they are tragic, for a lot of viewers of the shows, they’re the ultimate escap- ism, and nowadays that’s not a bad thing for people,” Kohm says.

Supplied photo

Published in Volume 78, Number 18 of The Uniter (February 15, 2024)