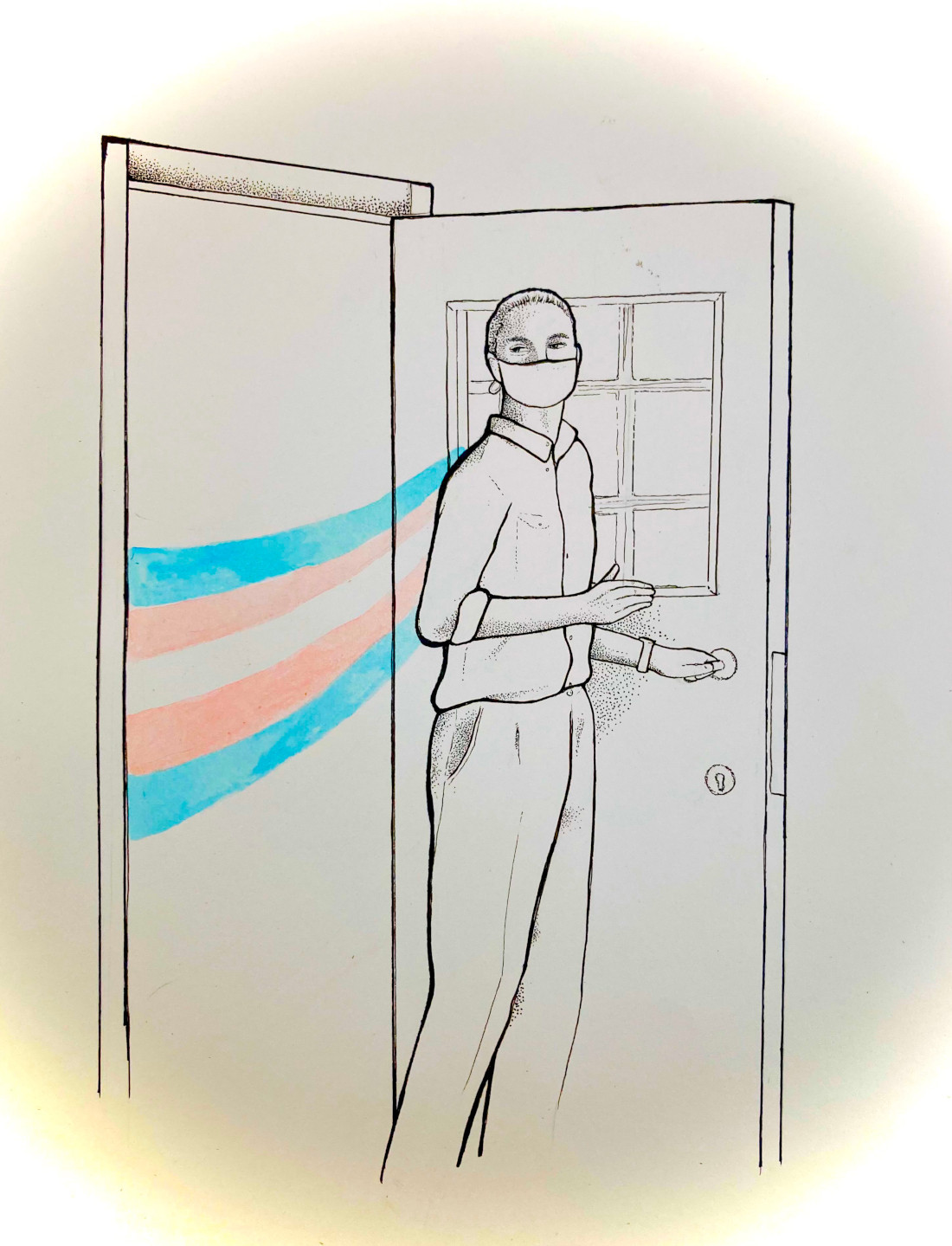

Transitioning in the pandemic

Starting testosterone during a lockdown revealed a different kind of isolation

Illustration by Gabrielle Funk

I’m one of the recorded 75,000 people – but for a long time, I wasn’t. The COVID-19 pandemic created circumstances that made me more visibly trans.

When I made the decision to start intramuscular testosterone injections in the fall of 2020, several people cautioned me against taking on such a dramatic change in already uncertain times. Their suggestions to wait for stability didn’t account for the added discomfort of gender dysphoria to an already galling pandemic lifestyle.

Suicide statistics, when compared with pre-pandemic rates, attest to the fact that quarantine has been especially challenging for the trans community. Social distancing, lockdowns and losing access to communities only exacerbate the systemic disadvantages of being trans.

When the province locked down for the second COVID-19 wave, my anxiety from the general uncertainty and fear caused by the virus was compounded by a worry that access to my injection training or supplies would be cut off. It was no longer a matter of whether now was the right time to start testosterone, but rather of how to navigate hormone replacement therapy within the pandemic.

My isolation during that lockdown in particular was layered. Despite living with supportive family members, both were cisgender. Although I regularly spoke with my queer and trans friends, none of them had experience with injecting testosterone. Klinic Community Health wasn’t offering a transmasculine or non-binary support group, and the one that met virtually through the Rainbow Resource Centre gathered once a month on a night I wasn’t available.

I had returned to Winnipeg from travels a couple months before the lockdown. With constantly changing public-health orders and the grotesquely transformed restaurant industry where I previously worked, stability seemed like a pipe dream.

The combination of apathy and novelty pushed me to come out at my new job in the spring, around the time the public-health orders started lifting. It’s unclear whether it was genuine respect or my new tenor voice that meant I was taken seriously about my pronouns.

The other place I came out was at my gym, where gender is mainly indicated by a binary system of prescribed weights, anyway. Choosing a heavier barbell served as a visual reminder for the others and an affirmation for myself that I was not boxed in by being assigned female at birth, even if it meant loading on fewer plates.

Despite this, isolation had skewed my self-perception. I misgendered myself in French on an application for a summer job because I thought I still presented more female and wanted to minimize confusion at a job interview. As public-health orders fell away and social opportunities ramped up, however, I was surprised to discover that I was consistently identified as male.

Strange men no longer tried to dance with me, and when they started a conversation, it was with a real topic in mind. Girlfriends no longer stood protectively close by as I chatted with their boyfriends. Older men, especially, stopped questioning my credentials and gave me an unwarranted amount of authority, especially in the workplace.

My male-passing body peeled back the veneer on gendered behaviour I hoped didn’t exist in 2022. I suddenly felt shielded in a bubble of privilege and reluctant to give up the safety of this position, which brought on a new kind of isolation: not being seen for who I really am.

I continue to out myself when it feels safe, partly because I forget I pass as male but mostly because to say nothing would erase my lived experience.

Charlie Morin is a writer and editor. They identify as a 45-pound barbell and a bean enthusiast of any kind (coffee, garbanzo, soy, etc.). Find him making up interpretive dances and removing Oxford commas.

Published in Volume 76, Number 24 of The Uniter (April 7, 2022)