Thoroughly modern milliner

Local hat-maker Helen Gair breathes life into a not-so-bygone artform

Tucked away in a quiet corner at the Winnipeg Art Gallery and Qaumajuq’s 2023 CRAFTED show, couture milliner Helen Gair of Helen Gair Millinery selects a red beret from her display and carefully places it on the head of a curious attendee.

Gair knows the hat works its charm best when worn. “People that you wouldn’t expect sometimes will sit down, and I will put a hat on them, and they become a vintage beauty queen,” she says.

The woman, who, moments before, appeared self-conscious and unsure, tilts her face to the mirror. She instantly straightens her posture, holds up her chin and breaks into a radiant smile.

This is the transformative magic of a well-made hat. This is the power of a milliner.

Helen Gair is the proprietor of Helen Gair Millinery.

Supplied photo - An illustrated advertisement for the wares of local milliners from the Feb. 2, 1902 issue of the Winnipeg Tribune.

A modern woman’s enterprise

The term “milliner” is derived from “Millaners,” men or women of Milan who were also purveyors of fine silks, ornament, ribbon and general finery. Essentially, “Millaners” were taste-makers, and the aristocracy depended on them to keep abreast of the latest trends.

“Millaners” today would be the equivalent of a TikTok fashion influencer or celebrity stylist.

Over time, the role of the milliner was more or less assigned to women who made dresses and hats. Haberdashers and hatters purvey mainly mens’ hats and fashion accessories. Male milliners do exist, though in the 19th century “male-milliner” crudely became derogatory slang for an effeminate, possibly homosexual man.

As a trade driven by women in a time when hats were all the fashion, millinery afforded many enterprising women an opportunity to make their own way in the world and a good living.

One such local figure was Elena “Lily” Jamon (1918 - 2009), born in Sirko, Man. She left Winnipeg in 1942 to become “El Jamon,” one of Toronto’s most sought-out haute couture milliners of the ’40s and ’50s.

According to an 1891 census, Winnipeg once boasted 31 dress and millinery shops providing expensive handmade garments for the city’s high-society women. Millineries were opening so fast, the Winnipeg Tribune had a column dedicated to millinery openings.

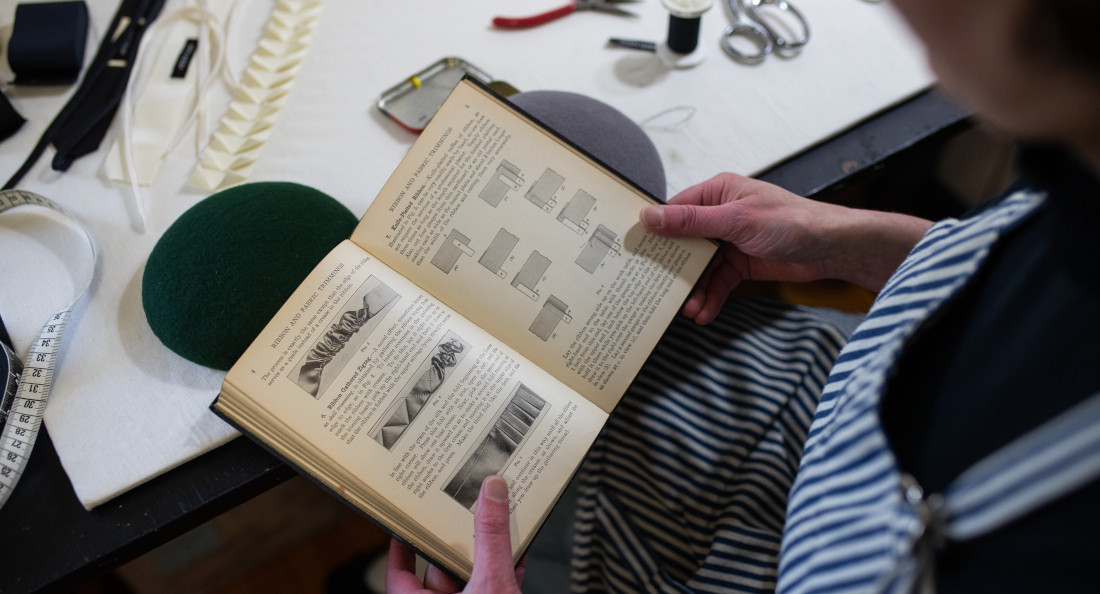

Materials and reference images in Helen Gair's home studio

Gair credits millinery for inspiring her to become entirely self-sufficient.

“It was a way that the woman could support herself without a husband or a man,” she says. Her decision to study millinery came when a major life event prompted her to go out into the world and reclaim her independence.

“Dressmaking and millinery – I mean, even my grandmother supported herself as a single parent with dressmaking – it was one of those things that strong, independent women sort of gravitated towards in my mind.”

Millinery is considered a niche industry in a post-industrial society accustomed to obtaining toques and baseball caps made overseas fast and cheap. Winnipeg’s cottage industry gave way to the advent of mass-manufacturing at the turn of the 20th century, a time when a burgeoning working class could scarcely afford custom clothing, much less a hat.

“Millinery was, at one time, taught in high schools as required courses for many, many years in the early 20th century,” Gair says. This skill proved not only useful for thrifty young women to fabricate their own hats from scraps and found materials, but it also provided them an entry point into the industrial workforce.

“I don't use glue or anything like that. Everything is hand-stitched.” - Helen Gair

A modern shift in trends

Gair, who is based in Winnipeg, has been a “hat lady” since high school, collecting and wearing vintage pieces as part of her daily costume. “It’s just such a passion, and an art form that is forgotten about,” she says.

Gair believes hats started losing their appeal in the ’60s and ’70s, when women were shedding patriarchal conventions, which included specific rules surrounding women’s attire.

“I love wearing a hat, but at a time it, you know, was part of the ‘proper’ female attire, which is a little ridiculous,” Gair says.

“Even just the side of the head that women are ‘supposed to’ wear hats on comes from a patriarchal sort of standpoint,” she says, referencing the Edwardian convention of men walking street-side, “so that, you know, he would get hit by a car first, I assume.”

“Women were supposed to wear their hats on the right side of the head tilting up, so that there would be no ‘obstructed view,’” she says. “I purposely wear my hat on the left side of the head most of the time.”

A romantic’s labour of love

Gair’s creations are steeped in nostalgic modernism and avant-garde sophistication. The picture of this lone hat-maker, carefully working her wool felts, silks and Petersham ribbons, provides a vintage snapshot of a time gone by.

The countless hours and days Gair expends to make a single hat stand in contrast to today’s fast-fashion world, but she manages to connect with clients who appreciate her craftsmanship.

“I don’t use glue or anything like that. Everything is hand-stitched,” she says.

Gair’s journey into the obscure art of millinery began with her studies in costumes at Dalhousie University. She later spent five summers training in millinery at European schools, including University of the Arts London Central Saint Martin under master hat-maker Judy Bentinck (who learned from Rose Cory, milliner to the Queen Mother).

“I decided to spend a lot of money when I was very young to learn the history of costume, which seems like a bad decision many years later, but it is the passion,” Gair says. Her independent spirit echoes the energetic creativity of the roaring ’20s.

Though hats are still manufactured and distributed from Winnipeg today by companies like Crown Cap (established in 1934), Gair is one of the few milliners left in the city who carry on the tradition of custom couture hat-making.

“There are other milliners in Winnipeg,” Gair says. “I don’t claim to be the only milliner in Winnipeg. I just don't know any of the details, but I assume they’re really awesome.”

An advertisement for Miss Cox Exclusive Millinery on Portage Avenue, from a 1944 issue of The Jewish Post.

The hat’s the thing

Jackie Van Winkle has worked as the wardrobe buyer and accessories person for the Royal Manitoba Theater Centre (MTC) for the past 28 years. Her duties, among many others, include millinery.

Much like Gair with her clients, Van Winkle can attest to the change in an actor’s demeanor when a hat is placed on their head.

“They stand a little straighter,” Van Winkle says. “They adopt the posture of the character they’re playing.”

The superpower of the milliner is their keen ability to provide the wearer a surprisingly metamorphic experience.

“It brings the character to life for them,” she says. “You can absolutely see it.”

In the 1921 book Individuality in Millinery, author Mary Brooks Picken writes, “in every person there is something that is attractive. Then, when you have decided what that is, you should try to cultivate it.”

Van Winkle’s work is not simply costuming an actor. She is helping the actor create a compelling story to enchant the audience.

Millinery has become much less prevalent in the 21st century due to mass manufacturing.

The last generation of Winnipeg milliners?

Through her years of sourcing hats and wardrobe pieces from local makers, Van Winkle has collaborated with perhaps the last generation of women working locally in the trade.

“There was an amazing milliner in town”, Van Winkle says. “She was on Corydon. We would hire her to make all these great big hats and do touch-ups for our shows.”

Andrea Brown, president of the Canadian Costume Museum, met Van Winkle’s mystery milliner at a fundraising event a few years back.

“Maria Havelka,” Brown says in an email to The Uniter, “who had Maria Hat Design, a longstanding 35-year hat shop in Winnipeg.”

Van Winkle first encountered Havelka in the ’90s when she was putting wardrobe together for an upcoming show.

“I always asked her to train me, but she never would,” Van Winkle says. “She went to Europe and was European-trained. She knew her stuff. She was so good.”

She credits Havelka’s craftsmanship for teaching her more about the construction of hats.

“I always tried to sort of see what she did. I’d look at stuff when we got it back from her, and I’d try to analyze it,” she says.

Van Winkle also worked with custom milliner Joanne Hunter of H’Attitude, a hat and accessory purveyor whose Portage Place Mall location operated for over a decade but has since closed and moved online.

“She was great,” Van Winkle says. “I think that it just got to the point where it wasn’t a sustainable business anymore.”

Despite the vanishing market for custom hats in Winnipeg, Van Winkle has an optimistic perspective on hat-wearing in general.

“They’re starting to make a comeback,” she observes. “I’ve noticed a lot of men on the street wearing hats. You see a lot of women. You see a lot of hats in the stores now,” she says, citing big, 1970s-style boho hats and fedoras.

Gair shares a similar optimism, but for custom-mades.

“In different countries, there is a very big market for millinery. In England, Australia ... there are hats everywhere, truthfully,” she says.

But they both also acknowledge that custom hats in Winnipeg are mostly a thing of the past.

“Mass manufacturing has pretty much ruined that,” Van Winkle says, citing how expensive it can be to buy and maintain couture hats.

“Do I do this to make money?” Gair, who by day manages the fit and pattern-making department at Mondetta, says. “No.”

Will millinery in Winnipeg ever make a comeback? Perhaps the evidence rests in the last of the closed-up millinery shops of the recent past.

Or, perhaps that Winnipeg legacy, or at least the lore, has been passed on to Van Winkle and Gair.

Gair points out a print ad for Miss Cox “Exclusive Millinery,” located at 389 Portage Ave. in the Boyd Building, appearing in a 1944 edition of The Jewish Post.

“I'd like to imagine that Miss Cox was a fabulous spinster wearing elegant garments every single day – someone like me,” she says.

Gair references the indespensable 1925 guidebook Ribbon and Fabric Trimmings, published by the Woman's Institute of Domestic Arts & Sciences in Scranton, Pa.

Published in Volume 78, Number 11 of The Uniter (November 23, 2023)