There is nothing new under the sun

Dissecting society’s ongoing obsession with revisiting pop culture moments of the past

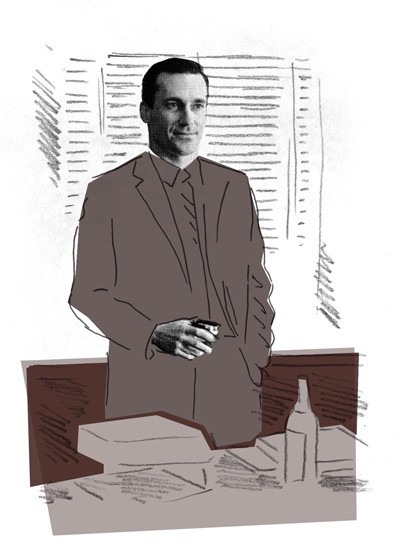

Mad Men – the aesthetically-stunning examination of a Madison Avenue ad agency in the early ‘60s – has been credited as the catalyst for a ‘60s pop culture revival.

Fashion blogs and magazines make frequent mention of how the increasingly iconic Donald Draper has heralded a new/resurgent era in menswear. Micheal Kors fall collection last year was dedicated to the decade. Oprah – a pop culture barometer, whether we like it or not – recently featured a Mad Men special on her show, with the audience attired in ‘60s era wear. The show and its cultural influence may now be called a legitimate phenomenon but it’s a phenomenon we have already experienced.

Much the way Michael Jackson’s death spurred an outpouring of revived interest in his life and music, pop culture tends to both cycle and recycle.

In his article, “Cyclorama,” Gregg Juke outlines what he calls the 20-year-rule, where what is fashionable now will experience a resurgence 20 years from now.

“Some of the overlaps between now and the ‘60s is a return of liberal and leftist energies in North America that draw attention to social justice issues, renewed anxieties about nuclear escalation, and rising consciousness of environmental destruction. I think this has to do with a similar set of geopolitical arrangements as much as a cyclical return,” Candida Rifkind, an English professor at the University of Winnipeg, said via e-mail.

One possible explanation for the 20-year-rule is that when one generation reaches maturity, they yearn for the simplicity of their early existence, thus becoming nostalgic for that which was most culturally visible during their childhoods.

“Another and equally compelling argument for pop culture cycles is something more like a 40-year rule that sees the generation in cultural dominance skipping over their parents’ youth culture and looking to their grandparents. This might explain the Mad Men phenomenon: looking to the era of our grandparents’ adulthood allows any of the natural tensions between children and their parents to be skipped over in the name of something more authentic,” said Rifkind.

As avenues to accessing the cultural moments of the past become more open – think Family Ties re-runs on YouTube – it appears as though our present culture is largely an inundation of nostalgia. The distinctiveness of our own time could potentially be dulled by dwelling on and attaching ourselves to the aesthetics, trademarks and contexts of bygone eras. We may require the advent of a few novel and inexplicable trends to jumpstart the latest cultural zeitgeist – a fixation on hats made entirely of Lego, which is spotlighted on Coolhunter.net, is one particularly unique possibility that may encourage us all to live in the now.

Rifkind explained however that despite this yearning for the past, culture remains dynamic.

“In terms of access to the past working against any authentic culture specific to our current moment, it’s always good to remember that any current culture is always a mixed or hybrid formation of bits and pieces from the past, the dominant culture of the present, and what cultural critic Raymond Williams called the ‘emergent’ culture that will become dominant in the future. So, pop culture doesn’t work on a linear timeline, it is always circling back and looking forward in the present moment.”

Published in Volume 64, Number 12 of The Uniter (November 19, 2009)