The three rules of fight clubs in Winnipeg

Highlighting common aspects in Winnipeg’s diverse combat sport scenes

“The first rule of fight club is you do not talk about fight club. The second rule of fight club is YOU DO NOT TALK ABOUT FIGHT CLUB.”

Although they may not be as iconic as Tyler Durden’s rules in the movie Fight Club, there are common guidelines in some of Winnipeg’s professional wrestling orga- nizations and martial art clubs that make them as enticing and iconic as the 1999 film.

Or that’s what combat sport participants and their fans might hope.

Premier Championship Wrestling (PCW) founder Andrew Shallcross, Bra- zilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ) and Isshin-ryū karate instructor Candace Daher and Winnipeg Pro Wrestling (WPW) competitor Mentallo all highlight three commonalities in com- bat sports clubs in Winnipeg: a welcoming community for participants and fans, a focus on diversity and multiculturalism and a promotion of healthy practices.

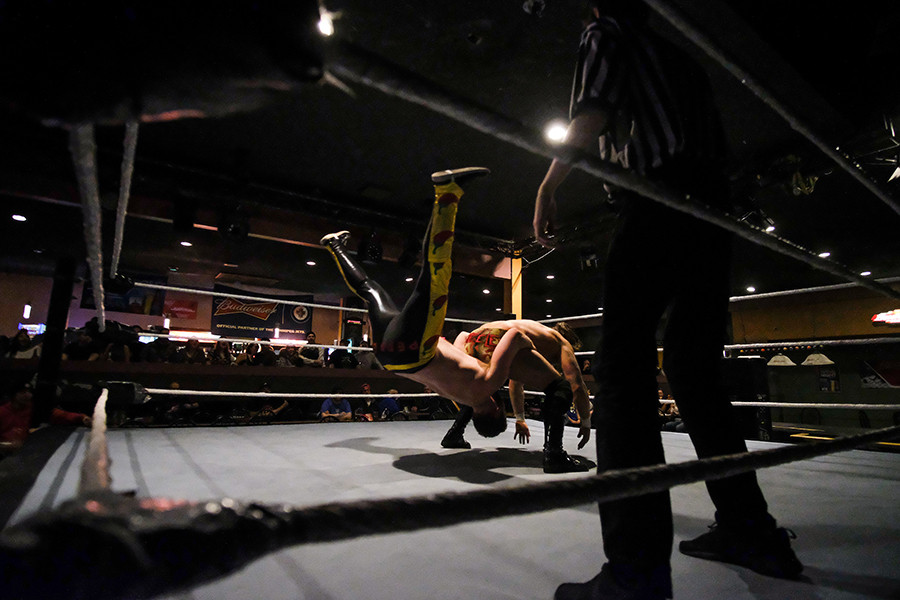

Tag-team wrestlers fight it out at a PCW event at Doubles Fun Club on Jan. 18.

These are not strict rules that every orga- nization must adhere to, or rules that every organization claims to follow, but these commonalities highlight a growth in inclu- sivity, cultural respect and recognition and a greater focus on safety in Winnipeg combat sport scenes.

Rule #1: Actually talk about fight club

Fight Club’s first two rules highlight its secrecy and intimate community, but they consequently rule out the general public who were not aware of it. However, Shallcross says PCW has an open and accepting community for prospective wrestlers and fans, and he points out that Winnipeg has always welcomed pro wrestling.

Sammy Peppers (left) fights Sydney Steele (right) during a PCW match at Doubles Bar.

“Winnipeg has had a long history of supporting pro wrestling, and the city was a regular stop for the old AWA (American Wrestling Association), which was a huge international promotion,” he says.

Shallcross notes that PCW’s support has ebbed and flowed during its 18-year tenure, but it has grown more in recent years.

“We now have a very strong fanbase that comes out to our events, and our wrestlers seem to have a lot of support. The fans are savvy, smart, they support a more athletic brand of wrestling, and they support us by buying tickets, merchandise and traveling for events,” he says.

“We really are about the grassroots, developing young talent and giving them a platform in Winnipeg to learn and grow as wrestlers. We have had several wrestlers to go on to wrestle globally, including for the WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) and the AEW (All Elite Wrestling), and the biggest star we have had thus far is Kenny Omega, who has wrestled with us for the entirety of our existence.”

Mentallo mentions that the pro wrestling community accepted him with open arms, and his wrestling career began shortly after leaving his high school basketball team and seeing a wrestling poster in a mall.

“At that time, I was considering either pro wrestling or kickboxing, but as a child, I always loved pro wrestling,” he says.

“I went to the show on a Wednesday, and I spoke with Vance Nevada, who became my very first trainer, and that

following Sunday, I was at my first training session. From there, I trained for six months. I set up and tore down the ring and did various shows in Manitoba for community clubs.”

Mentallo says the global wrestling community is welcoming, which he experienced firsthand in his travels for wrestling.

“When I decided to broaden my horizons, I went to the United States and did shows and training camps there. After that, I went to Mexico and spent nine months learning Lucha Libre. Just being in the wrestling business, acquiring different skills and getting better led to an opportunity for me to go to Japan, where I was able to wrestle there from 2010 to 2012.”

Rule #2: Fight club must always remain inclusive

Although a national 2005 Statistics Canada report states that women’s participation levels in martial arts were too unreliable to be published, interest has grown in recent years, and organizations like the Canadian Fighting Center (CFC) are taking steps to encourage women to participate.

Daher leads a women-only BJJ and self- defence program at CFC, and she says programs like this are important because of their positive impacts in women’s lives.

Candace Daher (blue) spars with Drayden Crossman (white) during a Brazilian Jiu Jitsu training session at the Canadian Fighting Centre.

“A lot of women get into martial arts purely as a hobby and for fun, but the deeper they go into it, the more they realize how empowered they have become and how much stronger they are,” she says.

“I would say about 60 per cent of the women in my cardio kickboxing class that I taught went into more dedicated martial arts because they really wanted to learn the skills instead of just losing weight. So the idea of personal empowerment, safety and the feeling of independence are some of the reasons I find that so many women are attracted to martial arts.”

Candace Daher is a brown belt in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. She trains at the Canadian Fighting Centre in Winnipeg.

Mentallo has travelled to compete and train internationally and has adopted the Lucha style, saying that many cultures and countries view wrestling differently.

“For Lucha Libre, it is very cultural and family-based,” he says. “Things are passed down from generation to generation, and that is why you see a lot of sons get into wrestling after their fathers. In the USA and Canada, it is viewed as a soap opera, where there is a lot of dialogue, but Lucha Libre is a more ingrained, family-based entertainment, and it is more like heritage.

“In Japan, it is the opposite, where it is viewed as a sport, so you find less talking and more action, harder hitting, and it is almost viewed on the level of mixed martial arts.”

Rule #3: Fight club must always be a safe place

A 2019 CBC article notes that WPW has banned the use of slurs and sexually or racially offensive remarks, and this practice is spreading, as leagues consider creating safer spaces for their participants and fans.

Shallcross says PCW is cognisant of its diverse community and says they try to provide a safe environment for all.

“The old way of thinking about wrestling has changed,” he says.

“Wrestling is trying to change more, and for PCW, we want to be at the forefront of that. We are aware of being diverse and attracting a diverse audience and talent. We are active in (the) LGBTQ community, and we are mindful that we have many fans from that community, that we have many female fans and many of our talents come from different backgrounds.”

Shallcross says Omega, who has wrestled for PCW as recently as 2019, is supportive of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, and he continues to be a role model for both wrestlers and fans.

“In Kenny Omega’s documentary, Omega Man: A Wrestling Love Story, which we were a part of, he spoke about LGBTQ support. He really sets an example for people including myself, and he sets the bar high for inclusiveness, which is something that we want to live up to,” Shallcross says.

Omega has made his support for 2SLGBTQIA+ communities explicit both through statements in interviews and through his wrestling performance itself.

His long-running story arc with New Japan Pro- Wrestling involved a relationship with his tag-team partner Kota Ibushi that many fans have interpreted as a gay relationship (a reading which Omega supports). Known collectively as The Golden Lovers, the duo’s storyline of splitting up and eventually reconciling has been called “a crucial step for queer representation in wrestling” by Paste Magazine.

Mentallo reiterates this support and says WPW wants to create an environment where everyone can feel safe.

“There are people of all genders, races and nationalities there,” he says. “No one is made to feel ostracized, and a lot of the promotions in Winnipeg are inclusive to everyone.”

Mentallo says that fans are not typically swearing and giving people a hard time, and he assures that if such a thing does occur, these people are eliminated from the scene immediately.

“Nobody wants to be involved with that behaviour anymore.”

Daher highlights the safety extended to participants, and she notes that more clarity should be given to point out that the winning formula of combat sports like BJJ and karate is to dominate your opponent and win through better technique, not violence.

“If it is truly a martial art, whether it is a stand-up art like karate or a ground-fighting art like sambo or BJJ, neither of them are violent (at) any time. When you look at mixed martial arts, it is a combination of arts like BJJ, kickboxing and wrestling. Each one of those has a very specific set of skills that are not about violence.” - Candace Daher

“I take exception to any martial arts being called violent,” she says.

“If it is truly a martial art, whether it is a stand-up art like karate or a ground-fighting art like sambo or BJJ, neither of them are violent (at) any time. When you look at mixed martial arts, it is a combination of arts like BJJ, kickboxing and wrestling. Each one of those has a very specific set of skills that are not about violence.

“Yes, the goal is to dominate your opponent, but that is the same concept in basketball, as you want to score more points than your opponent.”

“And if you see me, you would not think that I was a violent person. I look like a grandmother,” she jokes.

These rules point out the enticing nature of combat sport scenes in Winnipeg, which can draw both fans and participants to these organizations.

For participants, a significant training regimen to learn techniques, constant practice and healthy habits are viewed by some to be the keys to success. Although they may have their own unique set of challenges, Daher says these practices have a positive, all- encompassing impact on one’s life.

“It challenges my body and mind, helps strengthen my personal relationships and teaches me to deal with others and makes me aware of my limitations.” - Candace Daher

“It challenges my body and mind, helps strengthen my personal relationships and teaches me to deal with others and makes me aware of my limitations.”

Published in Volume 74, Number 15 of The Uniter (January 23, 2020)