The antisocial dilemma

What Netflix’s new docudrama gets wrong about social media

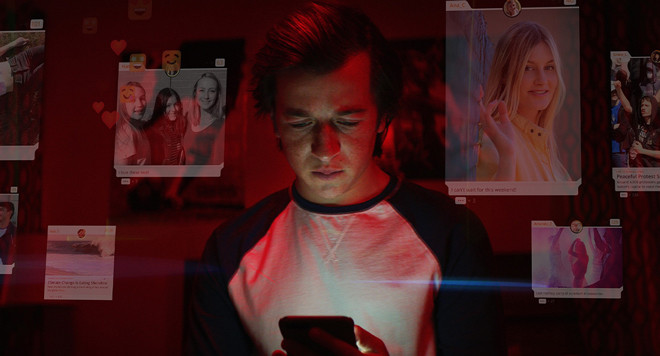

Near the beginning of Netflix docudrama The Social Dilemma, former high-level employees of Google, Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest are asked to identify the single underlying problem with big tech.

To a man – and most of the interviewees/co-stars are white men – the onetime executives and engineers are stunned silent. It’s surprising, given that they have plenty to say about subjects from psychology to sociology to communications science. But in that moment, they offer nothing.

If the viewer hasn’t jumped off the couch and screamed the answer at the television, they’ve perhaps at least guffawed while Claude Shannon and Stuart Hall turn over in their graves.

This subject is crying out for academic input, desperate for the expertise of cultural studies, eager to be seen through a lens of media theory that would at least clarify a cloudy and multi-layered topic.

“The bastard form of mass culture is humiliated repetition ... always new books, new programs, new films, news items, but always the same meaning,” Roland Barthes said.

“What would Roland Barthes say?” tends to be a useful question in matters of media. While we can’t ask the late pioneering French social theorist to help us make sense of Facebook, he already provided its DNA map some decades ago: hermeneutics, proairetics, semantics, symbolism and culture.

We shouldn’t take theory lessons from email designers or the inventor of the “like” button, no matter how well-meaning. The techies masquerading as professors in The Social Dilemma are well-meaning. They’re earnest, if not naïve, in their desire to create a friendlier social media landscape.

But they’re still selling something: the idea that social media as it exists is bad and unfriendly. It’s the “be-wary-of-big-tech” sub-genre of big tech – a pop category that actually serves to launder the tech giants of Silicon Valley via the notion that there can be an industry ideal as it exists under capitalism.

Market economics figures prominently in the film. The cast are under no illusions about the sea change that took place when Facebook and Twitter went public. They point out that “our attention is the product” and that social media is “a market that trades in human futures,” exchanging profiles built by user data for aggressively targeted advertising.

The film’s lack of depth is exposed in blanket statements about wireless applications “changing what you do, how you think, who you are,” as if such changes haven’t accompanied human evolution from the start.

Handheld technology has accelerated this process, but so did the development of writing, the printing press and the automobile, which completely altered the makeup of cities and the way we communicate. Virtual proximity is no less real than physical proximity, although anxiety over what is and isn’t real occupies significant attention in the film.

This is no doubt due to the information interference that affected the 2016 United States presidential election, the Brexit vote and numerous polls since. “Fake news,” don’t forget, was first used to describe the troll-farmed material and outlandish conspiracy theories that permeated Facebook feeds four years ago. The right wing later adopted the term, further confusing users and buttressing “lame-stream media” scoffers who were (and are) on the lookout for alternatives to the truths that merely reflect cultural and societal trends they dislike.

Kellyanne Conway’s infamous “alternative facts” terminology not only makes perfect sense in this context – although it was obviously nonsense – but also sheds light on what a lot of people want to see on their screens.

Social media algorithms aren’t mysterious, scheming voices instructing us to do this or that. They aren’t telling us anything new or introducing brand-new behaviours or ideas from scratch.

The cast of The Social Dilemma gives itself away by mashing their “attention is the product” premise, which is correct, with the idea that “disinformation is the business model.”

Of course it’s not. Is disinformation widely shared on social media? Certainly. But it’s not shared in a vacuum.

It’s here that the Shannon-Weaver model of communication is particularly useful. Each message or piece of information has a sender and a receiver. For the message to get from one to the other, there must be transmission, a channel for transmission and an ultimate reception, after which there is a feedback loop.

Social media is merely the “channel” in this model. It isn’t the “sender,” as it doesn’t, without human input, create the message. It’s not doing the transmitting, unless we’re sending information to ourselves. The “channel” brings the message to the “receiver.” Their interaction – a “like” or “retweet” – is the feedback loop. Further conversation can ensue. The process repeats itself.

This isn’t unique to social media. Protagoras and the other Greek sophists were practicing the persuasive arts as early as the 5th century BCE. But even they didn’t invent the desires and appeals to popularity they used to serve their purposes. It would take a particular hubris to assert to have done so, but it’s an accomplishment the interviewees of The Social Dilemma claim.

In stereotypical tech-presentation style, they put on headsets and pace onstage while lecturing about behavioural exploitation and the nature of truth. But there’s no dramatic curtain-raising to reveal that ultimate, underlying question to the problem.

The film’s strongest segment is at the end, when the cast is asked about how best to monitor or regulate big tech, especially regarding election advertising and data collecting. Aside from the inevitable utopian soliloquies, there are some pragmatic suggestions. Data could be taxed as a prohibitive measure, like a carbon tax. They proffer that governments could ban certain data harvests altogether, like they ban the harvest and trade of human organs.

Capitalism renders the latter scenario highly unlikely. There isn’t currently a moral imperative to treat social media as a human rights item. While a data tax seems sensible and possible, taxation is rarely a winning political strategy.

Besides, what the occasional alarmism of half-hearted committee hearings and films like The Social Dilemma ignore is that people mostly enjoy what big tech is giving them. They like looking at themselves, and they’ve enjoyed it ever since the 15th century invention of the convex mirror that, itself, accelerated human mediation during the Renaissance.

And this is that single, underlying problem – if it’s a problem at all – with Google, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and all the rest.

The problem is us.

Jerrad Peters lives, thinks and writes in Winnipeg.

Published in Volume 75, Number 05 of The Uniter (October 8, 2020)