Something’s been brewing

The evolution of Winnipeg’s local coffee culture

Inside the West Broadway coffee shop Thom Bargen, the whirring of coffee grinders and espresso machines mixes with the buzz of people mingling in the shop.

Two friends spot each other while walking in and strike up a conversation as they order their coffees. A father wheels in a stroller with his daughter, orders a “babyccino” for her and a latte for himself and plays “I spy” as they look out the front window. Up a flight of stairs, people sit along a long table, studying and reading with coffees beside them.

Parlour Coffee first opened in 2011

Cafés and counters

Winnipeg “didn’t have much of a coffee culture just because of who the main settlers were,” Christian Cassidy, a local history blogger, says. “They were from England and Scotland, and there it was primarily a tea-drinking society.”

The city’s roots in coffee can be traced back to the early 1900s, as more Italian immigrants moved to Winnipeg. Quickly, cafés started popping up, and some streets had multiple coffee shops next to each other.

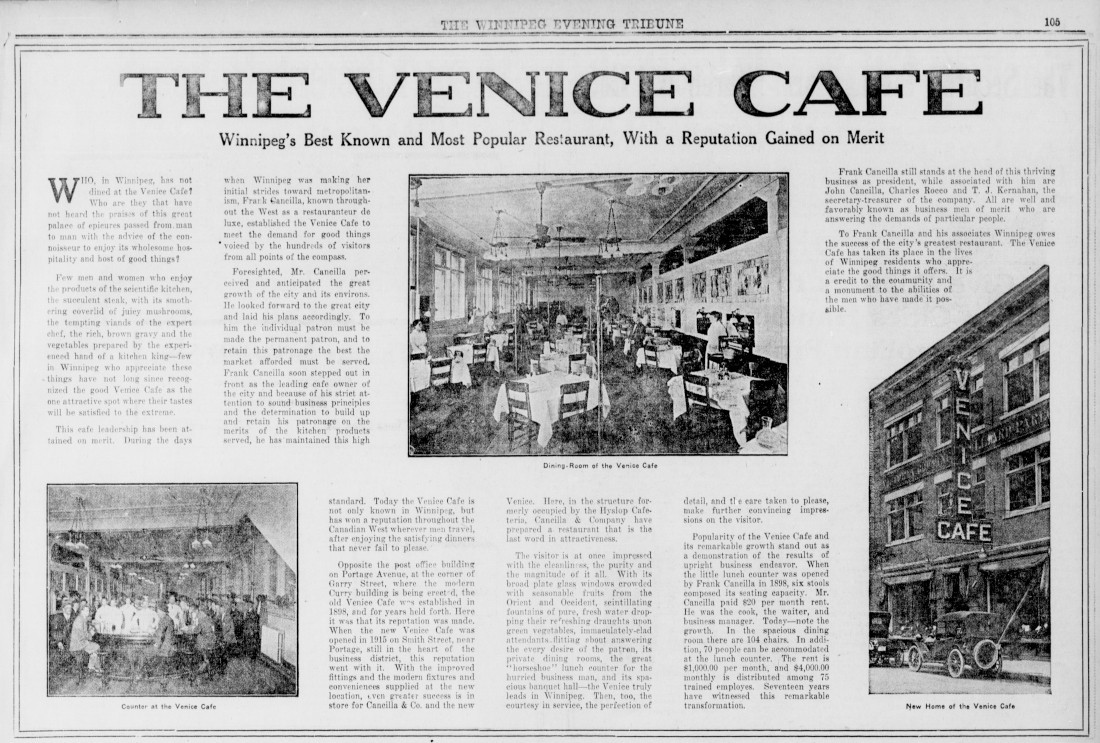

The Venice Cafe, owned by Frank Cancilla, opened in 1898 at the corner of Portage Avenue and Garry Street before moving, to expand seating, in 1915.

A 1915 article from the Winnipeg Evening Tribune says the Venice Cafe was well known not just in Winnipeg but also in Western Canada for its quality. When it first opened, the café only had six stools at its counter, and Cancilla was the cook, waiter and business manager.

Its expansion in 1915 included a large lunch counter that could seat 70 people, and similar seating options opened throughout the city.

The Electric Lunch chain (where present-day Modern Electric Lunch gets its name) had a couple of lunch counters throughout the 1920s, according to Cassidy’s blog, West End Dumplings.

The Murphy family, who moved from England, opened Electric Lunch in 1917. Brothers John and Henry Murphy opened Electric Lunch No. 2 in 1919, and the first location was rebranded as Electric Lunch No. 1.

Lunch counters “were generally open for breakfast, open for lunch, and they had a couple of tables … you had a few seats off to the side, but you had a coffee counter where you could sit down and just sit and sip coffee,” Cassidy says.

As time went on, lunch counters were renovated, and restaurants removed those spaces for coffee. The most famous chain of lunch counters was Salisbury House, which opened in 1931. Cassidy says they closed their last lunch counter-style location last year.

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune Archives, 1915

Neil Young performs at the 4D coffee house, 1964 - John Einarson (Supplied)

Music and mugs

John Einarson is an author and music historian. He says the birth of the coffee house in the 1950s and ’60s has a strong relationship with the growth of folk music in Winnipeg. While not original to Winnipeg, coffee houses were key to giving performers like Neil Young and Joni Mitchell the opportunity to grow and experiment in an accepting setting.

“Folk music isn’t played at community-club dances or performed in arenas. It’s a more intimate music that demands attention and a closeness and a close connection between the performer and the audience,” Einarson says. “Coffee houses were perfectly suited to create that kind of environment or ambience about them.”

Coffee houses were held in any space available, and some of the best coffee houses in Winnipeg were in church basements. Home Street United Church’s basement held a coffee house called the Latin Quarter on Sunday nights.

John Einarson is a Winnipeg music historian.

Commercial coffee houses also began to spring up. In 1960, the Fourth Dimension or 4D coffee house opened. This year marks six decades since Neil Young played his first coffee-house show at the 4D on Jan. 25, 1964. He was paid only in food when he performed, according to Einarson.

The death knell of coffee houses was the lowering of the legal drinking age in 1970. Younger people were listening to more rock and roll than folk music, and now they could go to the pubs to hear it, Einarson says.

“Had coffee houses been serving booze, (and) I can’t imagine that a church basement would get a liquor license, it would have been an entirely different situation.”

However, out of the coffee-house era, places like the Blue Note and the Ting Tea Room were born.

Despite being styled as a restaurant, Einarson says the Blue Note was influenced by the intimacy of coffee houses.

“It would serve liquor in a coffee pot, and people would pour it into a teacup ... looking like they’re drinking tea, and the cops could pop their noses and think ‘Oh everyone is drinking tea,’ meanwhile everyone was getting drunk,” he says.

Nils Vik, original owner of Parlour Coffee

Making waves

The 2010s saw independent specialty coffee shops gain popularity and pop up around Winnipeg. Within the span of two years, four mainstays of Winnipeg’s coffee scene started, with Parlour Coffee opening in 2011, followed by Thom Bargen and Café Postal opening in 2012 and Little Sister Coffee Maker in 2013.

Nils Vik, former owner of Parlour Coffee, only knew of Espresso Junction at The Forks and The Fyxx on Broadway as local independent coffee shops. While traveling in Montréal, Vik fell in love with coffee and came back to Winnipeg searching for something similar.

“I couldn’t quite find something that checked all the boxes, and I think, for the most part, it’s because there weren’t a ton of cafés in the city that were focusing primarily on just coffee,” Vik says.

He says most of the cafés at the time had other drinks or a large food menu, rather than just specialty coffee. He saw it as an opportunity to create a different café experience in Winnipeg by focusing on high-quality coffee.

Vik felt it was important to choose a space associated with history and character. He eventually found 468 Main St. in the heart of downtown Winnipeg, and it fit his goals perfectly.

When Parlour Coffee first opened, Vik saw people coming in who were already seeking out specialty coffee and people who had never been to an espresso bar.

“I’ve had many people tell me ‘Man, you ruined coffee for me, because now I’m stuck going to places like Parlour and Little Sister, and now I can’t drink the coffee I used to drink,” Vik says. “'I’m pretty proud to say that there (are) still customers that come in every day, and they were there in 2011, and they’re still there now.”

Vik partnered with Vanessa Stachiw to open Little Sister Coffee Maker in 2013. Together, they developed a relationship with Dogwood Coffee Co. in Minneapolis, then launched Dogwood Coffee Canada and began roasting their own beans.

A few years later, Little Sister Coffee Maker bought out the company and started roasting under their name.

While Vik doesn’t see many differences in style or quality of specialty coffee when comparing Winnipeg to other cities, he says Winnipeg’s shops are really friendly.

“If I’m in a bigger city like Toronto or Vancouver, it might be like, ‘Oh, that was a really friendly staff. That was great,’ and it sort of stands out,” he says. “Whereas here, that’s kind of what I expect from everyone, and that’s usually what I get.”

On Nov. 1, Vik decided to sell Parlour Coffee to focus on his family and other aspects of his career.

Café Postal on Provencher Boulevard

Quality first

Café Postal is the only bilingual specialty coffee shop in Winnipeg, according to Louis Lévesque Côté, co-owner and manager of the shop. He first started working at Café Postal as a barista six months after it opened, and then, six months later he was offered a job as manager.

Lévesque Côté says the approach of third-wave specialty coffee is built on the way coffee is farmed, purchased, roasted, brewed and served, using specific parameters along the way. The main goal is to emphasize the quality of the product and pay farmers what they deserve.

“Traceability didn’t really exist before when you were getting your coffee from Starbucks or from the grocery store,” Lévesque Côté says. “You’re lucky to know just the country that it came from.”

The coffee shop sources quality coffee beans and uses precise measurements to highlight the quality in the beans that’s already there, he says.

Lévesque Côté says the shop was ahead of its time in St. Boniface. Twelve years ago, people on Prochever Boulevard would’ve been happy with Tim Hortons being there.

“We had to convince the people of St. Boniface a little bit, at least at the beginning, that this way of making coffee was good and had a reason to be,” Lévesque Côté says. “We’ve put in a lot of work to develop a relationship with our community, who now supports us, and we try to show appreciation for this community.”

He says many people in St. Boniface appreciate how they can come into the bilingual café and order in French.

He sees growth in Winnipeg’s coffee scene, as more shops open up and more people become passionate about specialty coffee.

Lévesque Côté doesn’t see other third-wave coffee shops as competitors. He says cafés are collectively competing against corporate coffee chains like McDonald’s.

“I just have to look at our compost bin behind the shop, and it’s full of Little Sister, Parlour and Thom Bargen (cups),” Lévesque Côté says.

He says customers who want specialty coffee are now going to coffee shops based on which neighbourhood they’re in, rather than having one selected shop they only go to.

A barista prepares a coffee order at Café Postal.

Culture of cafés

Graham Bargen first opened Thom Bargen in 2012 with partner Thom Jon Hiebert on Sherbrook Street. Since then, they’ve opened two other locations on Corydon Avenue and Kennedy Street and are planning on opening a fourth in 2024 in Tuxedo.

Bargen says going to specialty coffee shops has been normalized for many people in Winnipeg. He says when many of these shops first opened, they all shared the same group of customers.

Now, he sees people coming in to support local coffee shops or to see a friend who works there.

Bargen says he notices changes in the trends of Winnipeg’s coffee shops.

“The shift now has been back to ‘Let’s make the best coffee we can but let’s be very unpretentious about that,’” Bargen says. “My goal here is to be welcoming and be a place where people can meet people and have a good experience.”

He sees the coffee-shop space evolving to focus on the culture of going into a café, as well as the quality of the coffee.

As independent coffee continues to grow in Winnipeg, Bargen hopes more people will start questioning the ethics of where their coffee is coming from and the practices involved.

Published in Volume 78, Number 13 of The Uniter (January 10, 2024)