Something in the water, and the soil, and the air

A closer look at a new report linking lead and crime

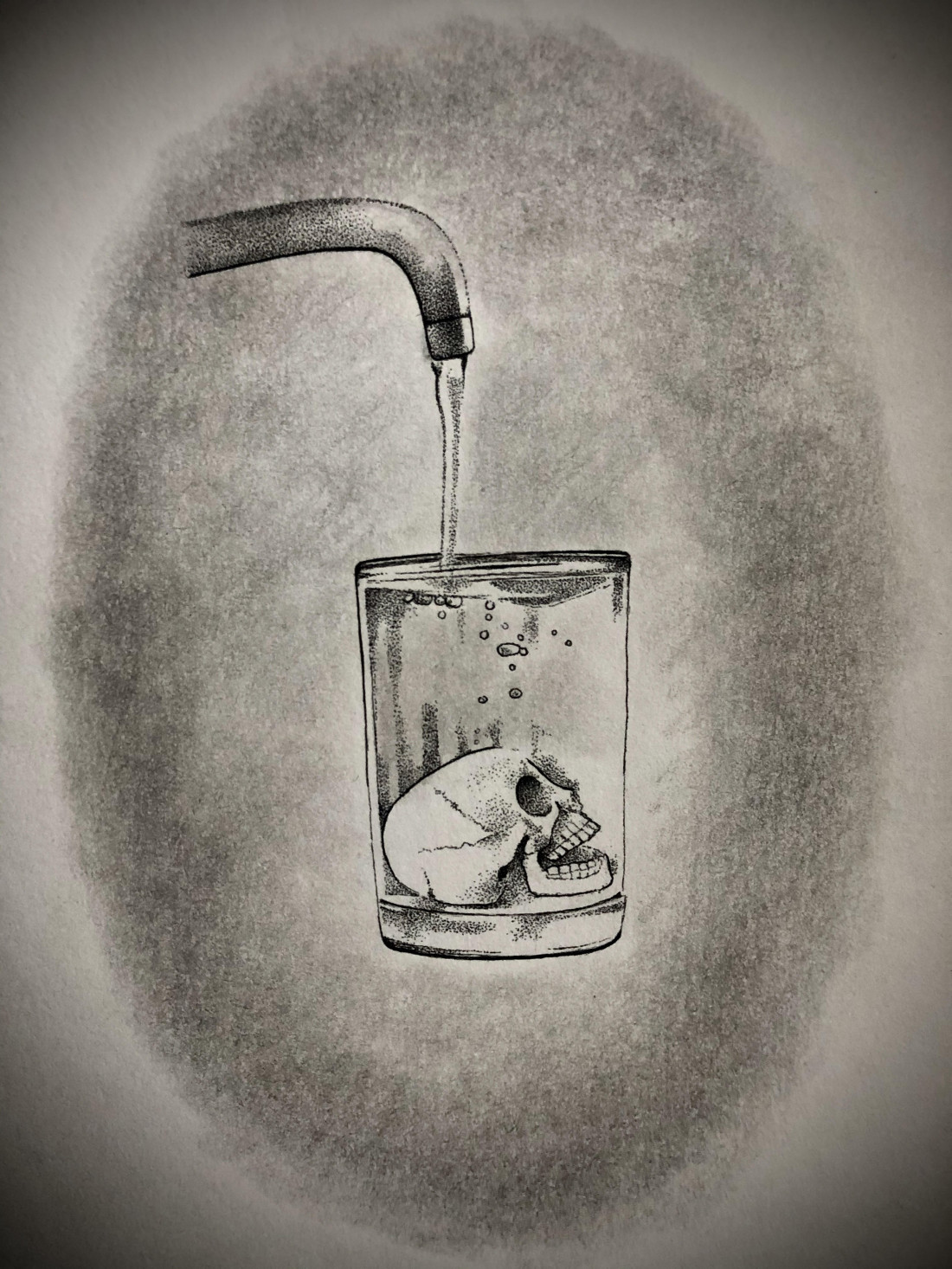

Illustration by Gabrielle Funk

It is a well-established fact that there is something in the water (and the soil) in much of Winnipeg: lead, and a lot of it.

Dr. Shirley Thompson, who has worked on lead testing in soil in south St. Boniface and North Point Douglas, says “the areas with lead contamination are pretty well-mapped in the city.”

While Thompson says the contamination from piped water and soil is well understood, there are facets of contamination that are less widely discussed, such as the legacy of leaded gasoline. “The soil in high-traffic areas and close to industry, close to railways, had lead,” she says.

“There are also ongoing emissions, and those aren’t really being characterized and evaluated, and those are from recycling shredders, from airports, which is making the situation worse,” Thompson says. “The other aspect is we’re not looking at multiple sources. We’re not looking at water and soil and vulnerability.”

Exposure to lead, especially from a young age, is dangerous, but provincial and municipal governments in Manitoba have been slow to respond meaningfully, so the Manitoba Liberal Party released a report in October reframing the health threat as a public-safety threat, titled “Lead and Crime in Manitoba: Urgent Action Needed.”

The report was authored by Dr. Jon Gerrard, who is the MLA for River Heights, a licensed physician and the health critic for the Manitoba Liberals. Gerrard says it came together in part because of constituents reaching out to him and Dougald Lamont, the MLA for St. Boniface and the leader of the Manitoba Liberal Party.

“As a pediatrician, I was very concerned about the impact of lead on children, and as I started digging into this area, I discovered that this is a very serious matter, and we need to be taking this much more seriously in Manitoba than we are currently,” he says.

“Lead and Crime in Manitoba” is 127 pages long and draws on many global studies on the impacts of lead. The report argues that because exposure to lead at a young age impacts brain development and is known to cause learning disabilities and behavioural conditions (particularly issues with impulse control and aggression) that have been associated with juvenile delinquency and violence, stronger provincial programs addressing lead exposure in children may be an effective way to decrease violent crime.

The case study on the impacts of lead in Charlotte-Mecklenburg County in North Carolina stood out to Gerrard specifically. The study observed over 3,000 children who had no or minimal lead exposure, had significant lead exposure and received intervention treatments, and who had significant lead exposure and did not receive intervention treatments.

The study found that while children with lead exposure did exhibit more “anti-social behaviour,” children who received intervention exhibited reduced behavioural symptoms.

“When you put everything together, it provides a very convincing case,” Gerrard says. “This struck me as being particularly important for Manitoba, because we have such high crime rates and particularly violent crime rates. The lead exposure seems to be related particularly to violent crime.”

Thompson, who is an associate professor at the University of Manitoba Natural Resources Institute, says that while she admires Gerrard’s work and commitment to the cause, this framing of lead poisoning does not necessarily contribute to a better understanding of the problem.

“The problem with these associations is that we don’t know if it’s a causative agent. We do know how lead acts in our body. And based on the very negative effects, children (should be) getting regular checkups to do this testing. I think that’s the important takeaway message,” Thompson says.

“I would rather connect it with health, and the health impacts are the ADHD, the trouble learning in school, which can lead to (increased interactions with the justice system). It’s further down the road than I would go, and I think it’s more than enough to say ‘the health impacts are there, and something should be done,’” she says. “I think it’s a medical problem that could be a social problem. I mean, it is a social problem either way, because it becomes an educational problem, but it starts with a medical problem, so let’s fix it there.”

Thompson says she would like to see governments apply the best medical practices to lower the risk and impacts of lead exposure, and while she wishes that “Lead and Crime” had a more clear message and was more closely tied to the definite facts about lead, its material is very comprehensive.

The report recommends the Government of Manitoba take initiative and do the kind of thorough testing that happened in the United States, but Gerrard says that has not been especially well-received by the provincial government.

In October 2019, Gerrard raised his concerns in the legislature about Weston School, a Winnipeg elementary school. Soil tests conducted in 2007 found unsafe levels of lead, but the findings weren’t made public until 2018.

Gerrard asked the minister of health, Cameron Friesen, if students at Weston had been tested for lead poisoning. Friesen took the opportunity to admonish the NDP for withholding the soil test results and praised the Pallister government for releasing the findings. (They were first exposed by a CBC News investigation.) To Gerrard’s question of whether children had been tested for lead poisoning, Friesen said, “I don’t know.”

The Progressive Conservatives are not the only party to avoid adopting best medical practices when it comes to lead. NDP governments in Manitoba have also failed to take lead exposure seriously, which Gerrard says is part of the reason for framing lead as a crime issue.

“It seemed like a way of emphasizing (lead), not only to the children and families involved. Crime affects everybody, and crime is often a hot issue in elections. Some (elections) are fought on the basis of who will reduce crime,” he says.

It is “really important to look at this as something that affects people who may not be living in an area with lead exposure. All of us must deal with this, through the impact on crime in addition to the impacts on kids and their lifelong outcomes.”

Thompson says she can understand the strategic reasons for the framing, but that framing lead as a crime issue still relies on less-solid science than framing it as a health issue.

“We know what lead does in our bodies, on child development, on all development. That is so strong and so evident,” she says. “I guess to make it news, you need another element.”

Published in Volume 75, Number 11 of The Uniter (November 26, 2020)