Slam city

What poetry slams mean to the local performance community

There are big dreams for performance poetry in Winnipeg, but conflicting views when it comes to slam competitions.

“Locally, slams are important because, counter intuitively, competition actually breeds community, in some ways,” Winnipeg Poetry Slam slam master Mike Johnston says.

Competitions connect people who have a love for the art, Johnston says.

“That passion cauterizes the connection between those who share it,” Johnston says.

If poets have mutual respect for one another during competition, they can grow through that shared journey, he says.

“We’re putting ourselves out there to be instantly numerically judged for art that is often very personal and meaningful. That journey seems to fit best when it’s people you get to know over time locally,” Johnston says.

Larysa Musick

“I tried putting the pieces into a poem. I performed that piece during a slam.”

He says it was an outstanding experience.

“How often in a lifetime do we really get to share that kind of connectedness with others and help carry the burdens of both their hurt and hope? Offering moments like that is what drives me to produce slams now,” Johnston says.

And he wants other people to come out and share their experiences through the art, as well.

“Our little community is working hard at evolving into something welcoming and supportive of all new voices,” Johnston says.

Mona Mousa, creator and director of Central Poetry Project, has a different take on the role of competition in performance poetry.

Derrick

Mousa believes poetry communities would be healthier without slam, due to the egoism that can develop through competitions.

“In slam communities, there lacks a little bit of gracious professionalism,” she says.

Slam is a good way to get involved in the poetry community and make connections, Mousa says. But she stresses that it is not the only way to be a part of the scene.

When curating a series through Central Poetry Project, Mousa’s first focus is always on diversity.

“I am a queer female of colour. I live under every minority and I think that recognition and that familiarity when people come to our series is pretty unique,” Mousa says.

Mousa works to curate events that draw people in and allow them to come and be themselves unapologetically.

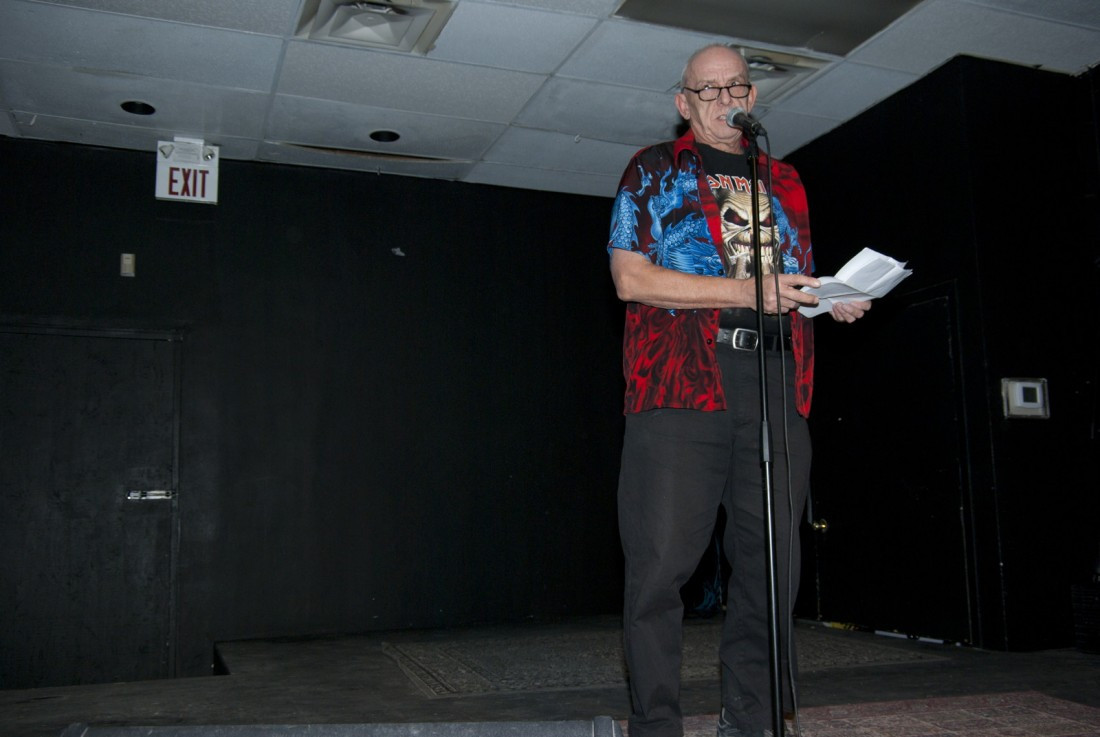

Mike

Despite this worry, both Johnston and Mousa express the importance and immeasurable amount of support within the scene.

Mousa has big dreams for the expansion of performance poetry in Winnipeg.

“I want to see it happen where we will bring a show and that show will always sell out,” she says. “Eventually, I would like to see line-ups for poetry.”

Follow Central Poetry Project on Facebook, or look for other spoken word groups if you’d like to learn more about slams and shows organized by individuals and collectives.

Published in Volume 70, Number 16 of The Uniter (January 21, 2016)