Off the Mats

Homelessness and addiction, and the resources that help

In Winnipeg, like most cities, homelessness is an invisible world that runs parallel to one populated by folks who don’t have to worry about poverty.

Panhandlers hold up signs and ask for bus fare, but besides the quick interactions Winnipeggers have with their impoverished counterparts, the thought of homelessness is out of sight, out of mind. The Winnipeg Street Census 2015, released in the fall of that year, momentarily shed some light on how many people deal with homelessness.

But what is that experience really like?

Main Street Project runs a housing program out of the Bell Hotel. (Photo by Callie Morris)

For Arthur Szymkow, it’s been a long two decades of struggling with mental health issues that have kept him unemployed and in and out of housing.

Today, Szymkow lives at Mainstay, a transitional residence and one of Main Street Project’s (MSP) many services. He’s frustrated that despite an extensive resume, at 63, he is encouraged to take part in work placements that have never resulted in stable employment.

“I used to conduct $20 million worth of business in the electrical industry,” Szymkow says. “If you want to keep people occupied, because there are no jobs, what’s the best thing to do? Give them a training program.

“I asked one director … ‘How many people do you go through a month?’ He said 1,200. How many end up with employment? About 30. How many keep that employment after three months? About five.

“It’s not effective at all.”

Szymkow was assigned to several mental health workers after his mental state deteriorated. But like many others in his position – unexpectedly homeless or reliant on social services – he was hit with barrier after barrier.

“It’s called horizontal. There’s no change. I’m still in transition,” Szymkow says. “I can be transitioned a little up or a little down. What’s my next step? What, in 35 years, has happened to me? Nothing … The people who are supposed to be gate openers, seven times out of 10, are gate closers.”

Arthur Szymkow says that current support systems don't work well for folks (like himself) who also have mental health issues. (Photo by Alana Trachenko)

Nelson Gzebowski didn’t expect to find himself on the streets, either. Gzebowski lives at the Bell Hotel, another arm of MSP’s housing programs. He lived in North Kildonan for 27 years and spent 30 years working for a company that went out of business.

“After I used up all my savings, which didn’t turn out to be as much as I thought it was, I ended up on the street, and then at the (Salvation Army) Booth Centre,” Gzebowski says. “I would rather be on the street than go back to a rooming house.”

Now, he lives in housing that allows its residents to use drugs and alcohol onsite while they deal with addiction, but he’s never felt more secure or at home.

MSP’s volunteer and community engagement coordinator Carla Chornoby says Winnipeg would greatly benefit from more housing that allowed intoxicated folks to stay. It’s a system that works, and one that tackles the sticky issue of homelessness and addiction.

“The Bell is one of the best concepts,” Chornoby says. “If we had more of those, we wouldn’t have a homeless population.”

Nelson Gzebowski became homeless when his savings ran out, and he's seen the challenges of securing steady housing and a job after living on the streets. (Photo by Callie Morris)

Housing First

“Ultimately we’d like them to (be sober), but the reality is that some may never stop,” Chornoby says. “We need housing 24 hours a day, that’s not just for mental health … but what if they have mental health and addiction? And there’s none for addiction.”

Homelessness and addiction are often associated with each other, and the statistics back it up. Patti Nixon, manager for the detox and stabilization centre at MSP, says that out of all the clients they see for addiction issues, half of them report absolute homelessness.

“There’s the stress of being homeless, more anxiety, fear, depression, which can lead to substance abuse,” Nixon says.

And because issues of addiction and trauma are often passed down through families and throughout communities, environments become a key factor in why someone with addiction will likely stay addicted.

Andy Meekis, 46, is known as a leader and friend throughout his community. Meekis lives at Mainstay, and although he’s been to treatment programs, he continues to struggle with alcoholism.

“I’ve been homeless most of my life,” he says. “I couldn’t stay at my dad’s, and I couldn’t stay at my mom’s.”

He says his friends struggle with addiction too, which has made it difficult for him to maintain a sober lifestyle.

“I have friends who have passed away from addiction,” he says. “I’m always there for them. I try to tell them, quit it, but they can’t … they call me a leader. They call me a boss. But I’m not the boss.”

Meekis spent two months at the Peguis Al-Care Treatment Centre, but it wasn’t long enough.

“When I got out, I had money and I tried to quit,” he says. “But I was walking around and everybody is drinking. I just quit for two days and got out and couldn’t handle it. They were my friends.”

Chornoby says that it goes even further than friends and community for some of their clients, and that removing someone from their network can have damaging effects as well.

“If you move someone outside the community, they’re lonely. They start that whole thing again,” she says. “They’ve had trauma. The Indigenous community, we’ve had that long history of trauma, some have started sniffing at four years old. What they need is people to care about them.”

With that in mind, MSP works under a housing-first philosophy.

MSP director of transitional and supportive housing Adrienne Dudek says that while some facilities operate under an abstinence philosophy, both models are important and necessary to support vulnerable people.

“By allowing people to use, it’s a harm-reduction model,” she says. “For different people, it’s different paths … but with us, we’re low-barrier, so quite often, people who are not able to access services other places can still access them here.”

She says they also work with other organizations and try to refer folks to where they need to go. When she first got into her line of work, Dudek says that one thing surprised her above all – anyone can have issues with addiction, but it’s the homeless that are most stigmatized for it.

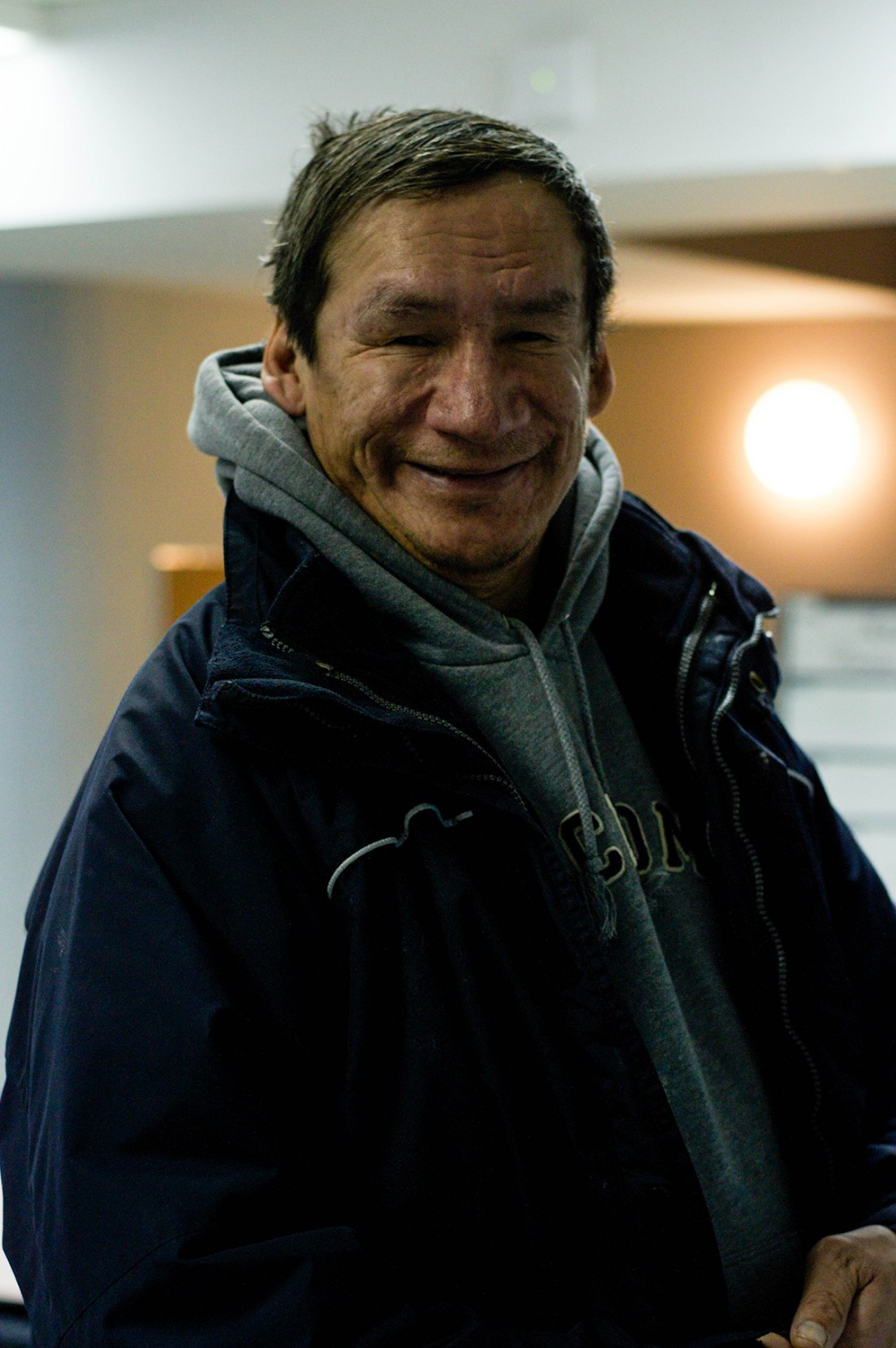

Andy Meekis, 46, is known as a community leader and lives at Mainstay. (Photo by Alana Trachenko)

Burdened with blame

Gzebowski says that he’s seen it many times – homeless folks are asked, why not just get a job? Why not just stop drinking or using drugs? It should be easy enough, right?

“Yeah, but are you willing to hire that person or take that person as a tenant in an apartment, with all the baggage they have? Straight off the street?”

He says that won’t solve any problems.

“If there was some way to take a first-time homeless person and get them straight into housing and a job within months, that’d be great. But once they’re homeless and once they can’t find a job or a place to live, the longer it takes, the more of a trap it is.”

It’s a systemic issue, Dudek says, and until it’s resolved at the core nothing will change.

“Until we fix things systematically, and provincially and federally, we’re not going to see change at our level. Homelessness is not going to go away.”

A housing-first philosophy is the best frontline strategy, according to Dudek. But where governments allocate money and which programs they support also impacts homelessness on a larger scale.

Hearing Szymkow and Gzebowski’s stories, it’s no wonder that the options that do exist don’t appeal to many people. Rooming houses run by landlords who have little interest in maintaining a property are not a safe or healthy place to live, they say. And when given the option, many choose to stay on the street.

“They’ll say, ‘No, I’m good where I am. I feel safer sleeping with my friend under the cardboard here and being safe rather than being on the mats (sleeping in shelters) and being in a cot,’ so there are a lot of people who, pride-wise, maybe don’t know what’s out there,” Dudek says.

Accessing resources for addiction can be challenging too, and although the government is beginning to treat drug use as a health problem, homeless folks are still met with blame more often than not.

“You’ll have a different demographic of people who are housed and make a lot of money and drink a bottle of wine every night, and that’s not seen as an issue,” Dudek says. “But someone lives down here on the street and drinks a bottle of wine a night, and the whole perception of their life is so entirely different … Addiction does not discriminate.

“People think that people who experience homelessness are lazy, but they are survivalists. I challenge anyone to walk in somebody’s shoes, who has no place to go all night when it’s Winnipeg and it’s -45.”

It’s an uphill battle, but MSP staff say it’s the little things that keep them going – it’s seeing their clients make it up off the mats.

To donate, volunteer, or learn more about MSP, visit mainstreetproject.ca.

Published in Volume 71, Number 20 of The Uniter (February 16, 2017)