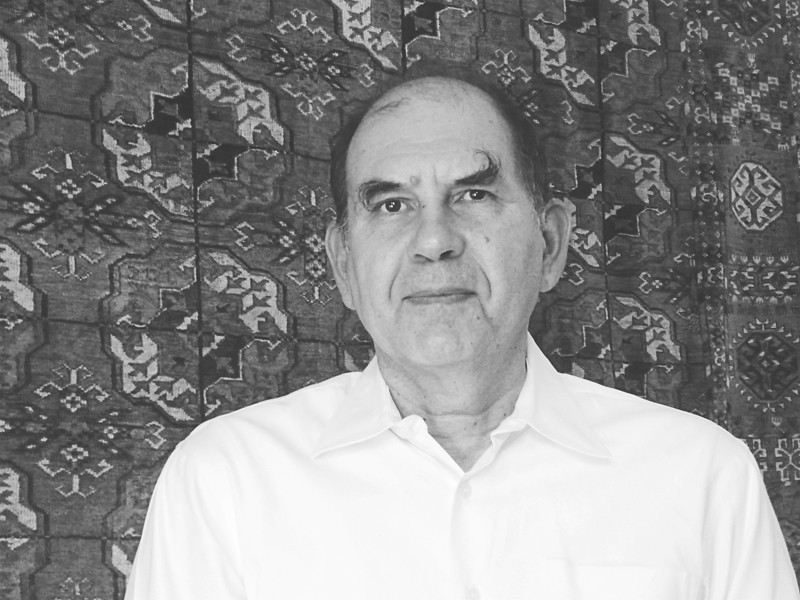

Nikos Salingaros: Biology, the city and responsible design

Distinguished urbanist and architectural theorist to speak at St. Margaret’s Anglican Church

Since the early 20th century, cities around the world have been moving largely - and steadfastly - in the wrong direction.

On the one hand, cities have been designed around the automobile rather than the human being, contributing to wasteful sprawl that ignores the fundamental principles of urbanism.

Namely, these suburbs lack a mixture of commercial and residential uses, high-density development and pedestrian friendly streets.

On the other hand, cities have been overrun with novel, poorly functioning architectural forms that ignore the basic rules of good design.

Namely, these new buildings are not ergonomic (proper entrances, functional) and they make people feel psychologically and physically ill at ease.

In order to correct this historic injustice, cities need to return to fundamental, timeless truths about the universe. They can be helped along in this undertaking by the historic foundations of organized religion.

So goes the argument of Nikos Salingaros, a visionary urbanist and architectural theorist who will be lecturing on Monday, Oct. 15, at St. Margaret’s Anglican Church as part of their annual Slater-Maguire lectures.

“Organized religion is capable of holding down to fundamental truths that science does not have, or it complements the physical truths that science discovers,” Salingaros said over the phone from the University of Texas at San Antonio, where he works as a mathematics professor. “The traditional religions have evolved a set of rules that help society remain healthy and that provides a tremendous stabilizing force.

“Unfortunately, organized religions have not taken a stance to maintain the natural geometry of architecture and I’m rather disappointed that several organized religions have actually done the opposite. They have embraced these inhuman architectural forms to build new churches; ... today it is alarming because many, many new churches are being built in the inhuman system.”

In his 2006 book A Theory of Architecture, Salingaros argues traditional architecture intuitively maintained a connection between the built form and the mathematical rules for geometric order.

Over the past two decades there have been countless experiments measuring the physical and psychological responses of human beings to the built form. The correlation between traditionally built architecture and improved health and mood are indisputable, he argues.

In short, when buildings are built around the mathematical rules of geometric order, human responses are measurably more positive.

“For a 100,000 years, people built intuitively in order to have this correct connection, but since the beginning of the 20th century, architects have gone crazy and have started to build buildings that contradict natural order,” Salingaros said.

The trend away from traditional architecture happened in North America and in Europe, for vastly different reasons.

In Europe, the rise of fascism and communism in the early 20th century and after the First World War led to regimes that were hell bent on “smashing the past,” which included traditional architecture.

As a result, they built poorly functioning novelty structures that were intimately linked with an ideological agenda.

“The idea of these new forms was linked with a bright new utopian future and both the Nazis and the Marxists made this link,” he said. “We have gotten stuck at that point, with identifying futuristic looking forms or buildings with progress, which is totally false.”

In the United States, the move away from traditional architecture was led largely by a greedy construction industry, which saw dollar signs in the opportunity to “re-build the American city.”

In North America, this architectural re-building was coupled with the creation of what Salingaros calls the “car city,” which ignores the fundamental principles of urbanism.

While he remains optimistic about urbanism - citing the decisions of many American cities to remove their expressways and to stop building garish skyscrapers - Salingaros is “terribly pessimistic” about architecture.

“It has to do with a change in philosophy and I don’t see that taking place,” he said. “In fact, I see the opposite.”

Nikos Salingaros will be lecturing at St. Margaret’s Anglican Church (160 Ethelbert St.) on Monday, Oct. 15, at 7 p.m.

Published in Volume 67, Number 6 of The Uniter (October 11, 2012)