New visions for accountability

The ongoing project of unravelling rape culture

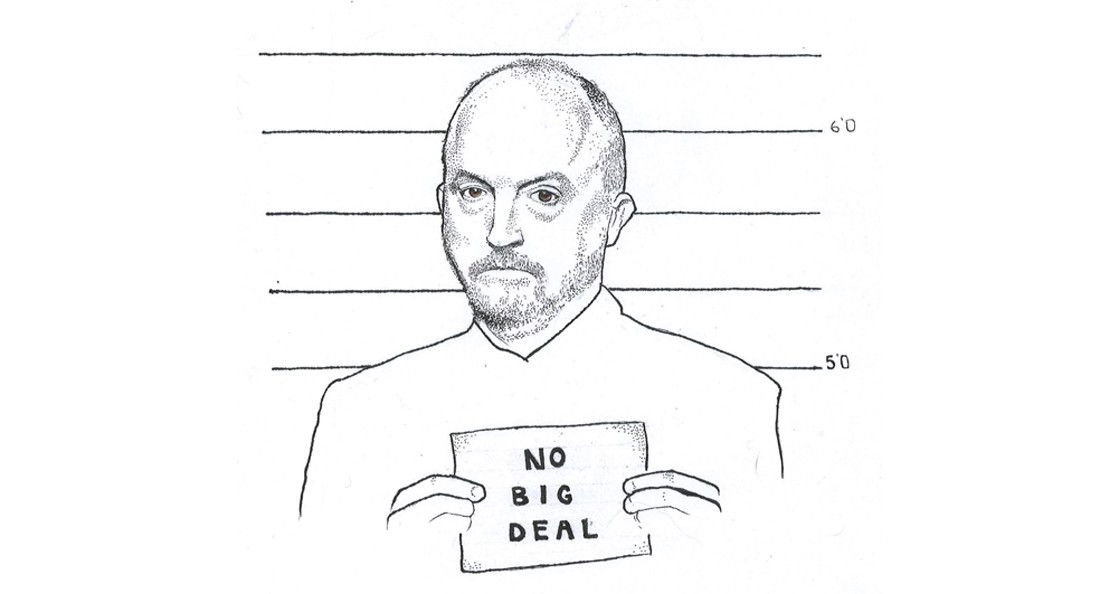

Louis CK received a standing ovation after his first comedy set since admitting he forcibly exposed himself and masturbated in front of numerous unconsenting women.

It seems incongruous that CK, a man who used his body to block the door as women tried to escape his room, would be welcomed back after just nine months in hiding. Why is the general public so quick to forgive victimizers, at the expense of their victims?

In her recent article for The New York Times, Roxane Gay observed, “It is easier, for far too many people, to empathize with predators than it is to empathize

with prey.”

This idea, that we recognize something of ourselves in stories of sexual misconduct, suggests an underlying awareness of rape culture and our own potential to harm – but we quickly turn away from this incriminating thought.

Instead, survivors are disbelieved, taunted and ignored. Men accused, and even convicted, of sexual violence are defended and rallied around. A true reckoning with rape culture would mean putting ourselves on trial and admitting this is a systemic issue, not the one-off actions of a few bad men.

The term “rape culture” describes a society which normalizes widespread sexual violence, predominantly men’s sexual aggression toward other genders. Evidenced by catcalling; groping; rape jokes; victim-blaming; upskirting; rape prevention tips; the frequency of sexual assault; the lack of rape convictions; parental rights for rapists, and so much more, rape culture is everywhere.

I find it compelling to frame this issue as one that connects us: we are all struggling with the damaging effects of a sexual education devoid of consent, autonomy, empathy or self-reflection.

If we imagine accountability as the undertaking of understanding and undoing rape culture, a call out becomes a call to action and an opportunity to learn from our mistakes.

But when called out, most tend to deny reports – and it is their victims who suffer.

Locally, we can look to Tara Hart, who just last year was mobbed and forced into hiding after speaking out about domestic violences charges laid against her then-partner, Wab Kinew, in 2003. Despite sharing intimate remembrances of the incident, Hart was defamed to protect Kinew’s image after he denied her story.

In this #metoo moment, generations of men raised under rape culture are seeing their own violence mirrored back at them – especially in men like Louis CK and Aziz Ansari, whose “bad date” style of predation was downplayed as "not that bad." Overwhelmingly, the male population has chosen to forgive their cohorts and look away from their own misconduct.

What if accountability was a service paid to the people you harmed? What if accountability looked like dismantling rape culture, every day, for the rest of your life? Because that’s how long the victims of sexual violence live with their experiences; we may heal, but we are changed forever.

If men like Louis CK were held to a model of accountability based in service to survivors, a societal shift to a genuine culture of consent might be possible – and nine months’ holiday would hardly be deemed sufficient.

Mandalyn Grace is a writer and organizer turning over ideas about sustainability, community and radical empathy.

Published in Volume 73, Number 2 of The Uniter (September 13, 2018)