Learning to share the roadway

Cyclists and motorists can’t treat busy urban streets as highways

In May, I spent a couple of days cycling around Manhattan and Northwest Brooklyn. My initial plan, as I nervously set out from my friend’s place in the East Village that first morning, was simply to get up to Central Park with as little time spent on the busy streets as possible.

Central Park, where most of the winding roadways are essentially car-free, was fun to ride in, and I crossed the length of the park in what seemed like a few minutes.

But what was just as fun was riding in the busy streets of Manhattan, which I soon discovered were safe and easy to navigate. Traffic moves slow, and so darting in and out of different lanes on Sixth Avenue was not the same act of suicide it is on Portage Avenue.

I felt safer rounding Columbus Circle, or riding through Madison Square for the first time, than I ever felt making a left turn from Portage onto Main. And the absence of yokels racing by in their pickup trucks, urging me to “get off the road, faggot” was a pleasant reminder that I was no longer in Winnipeg.

This difference between cycling in New York and in Winnipeg is caused by the density and diversity that exists on the roadways of New York.

In Winnipeg, 50 years of traffic engineering has enabled a deeply entrenched car culture, as formerly vital streets were cheaply fashioned into conduits to suburbia.

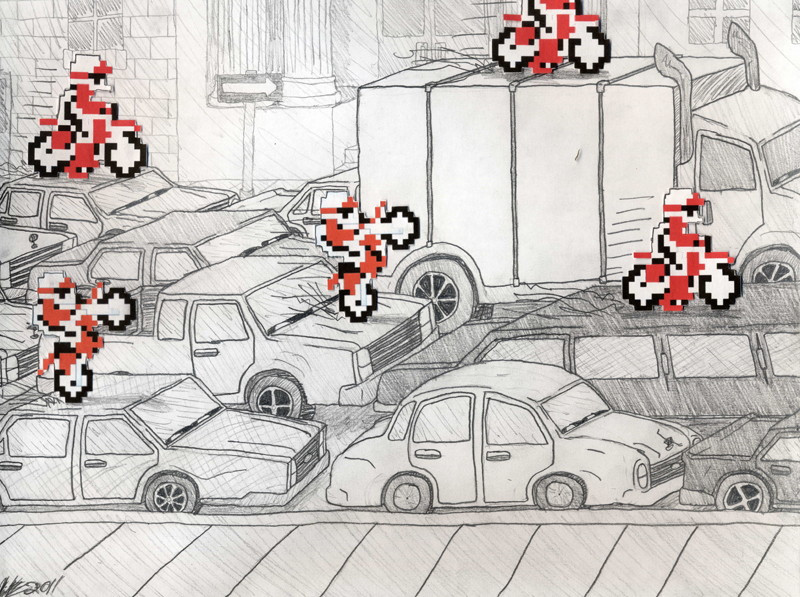

In Manhattan, no one drives a motor vehicle without expecting to share the roadway with cyclists - from couriers on road bikes to the Kamikaze-like food delivery guys on mountain bikes.

And it’s not just cyclists: there is also an endless supply of delivery trucks, buses and taxicabs. And then there are pedestrians, who assertively jaywalk or cross against the light when the opportunity permits.

“ Drivers in Manhattan have to use their brains and be cognizant behind the wheel. In Winnipeg, they usually don’t have to, which is why so many motorists here claim the cyclist they sideswiped “just came out of nowhere.”

In other words, drivers in Manhattan have to use their brains and be cognizant behind the wheel. In Winnipeg, they usually don’t have to, which is why so many motorists here claim the cyclist they sideswiped “just came out of nowhere.”

It works both ways, and cyclists have to focus on the road as well. On a bike in New York, there was little time to stare up and marvel at the ornate cornice of an ancient skyscraper, or to double check if that was Michelle Williams back there.

Like most North American cities recently, New York has undertaken a massive effort to build new cycling infrastructure, such as dedicated bike lanes. Great news, but some New York cyclists are finding the bike lanes slower and more dangerous than the street was before.

Built at the sidewalk edge, between a row of parked cars, Manhattan’s bike lanes fill up with pedestrians and delivery people carting wares from trucks to storefront businesses. And so these bike lanes have become only useful and safe for slow cyclists. For anyone in a hurry - commuters, couriers or kids from Winnipeg who would like to cross town before the day’s end - riding in general traffic is a better option.

Cyclists should remember that city traffic is best when it is slowed down and congested with different users. Fast moving streets are dangerous ones, and even a properly designed bike lane (something Winnipeg does not come close to having presently) can only do so much.

Bike lane planning should not function on the same objective as conventional traffic engineering: to make rapid movement as efficient and easy as possible, where the less sensory power utilized by the vehicle operator, the better.

Great streets are able to do many things, but they cannot do any one of them perfectly. Just as there are many kinds of cyclists that will use a good bike lane, there are even more kinds of users that will use good streets generally.

This complexity of the street is necessary if we are to have healthy neighborhoods, and without healthy neighborhoods, we don’t have places that are compatible with cycling as a practical transportation option - we just have two conflicting sets of quasi-freeways.

Robert Galston has written on urban issues since 2005 in his blog The Rise and Sprawl, and for the Winnipeg Free Press and The Uniter. He is currently studying at the University of Winnipeg and is employed at the Institute of Urban Studies.

Published in Volume 66, Number 9 of The Uniter (October 26, 2011)