Inflation vs. students

How the rising cost of living hits university campuses

Russia’s war in Ukraine has caused massive global impacts. In retaliation against Russia, many countries have stopped importing Russian oil. As such, many different industries are affected, causing a ripple effect throughout different economies.

Canada is not immune to these effects. Although Canada has a strong oil supply from its own soil, demand makes these costs higher. When combined with preexisting instability from the COVID-19 pandemic, global supply-chain problems and radical changes in the labour market, Canada has felt the shockwaves of the global inflation surge.

Winnipeggers have already seen the effects of this oil shortage. Gas prices are at an all-time high. Those who commute with their own vehicle face higher expenditure the more they travel.

But Canada’s supply shortage on oil doesn’t just affect gas prices.

Although inflation has been a problem since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become worse due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Canadians suffer the impact of high inflation when prices go up and incomes do not quickly follow.

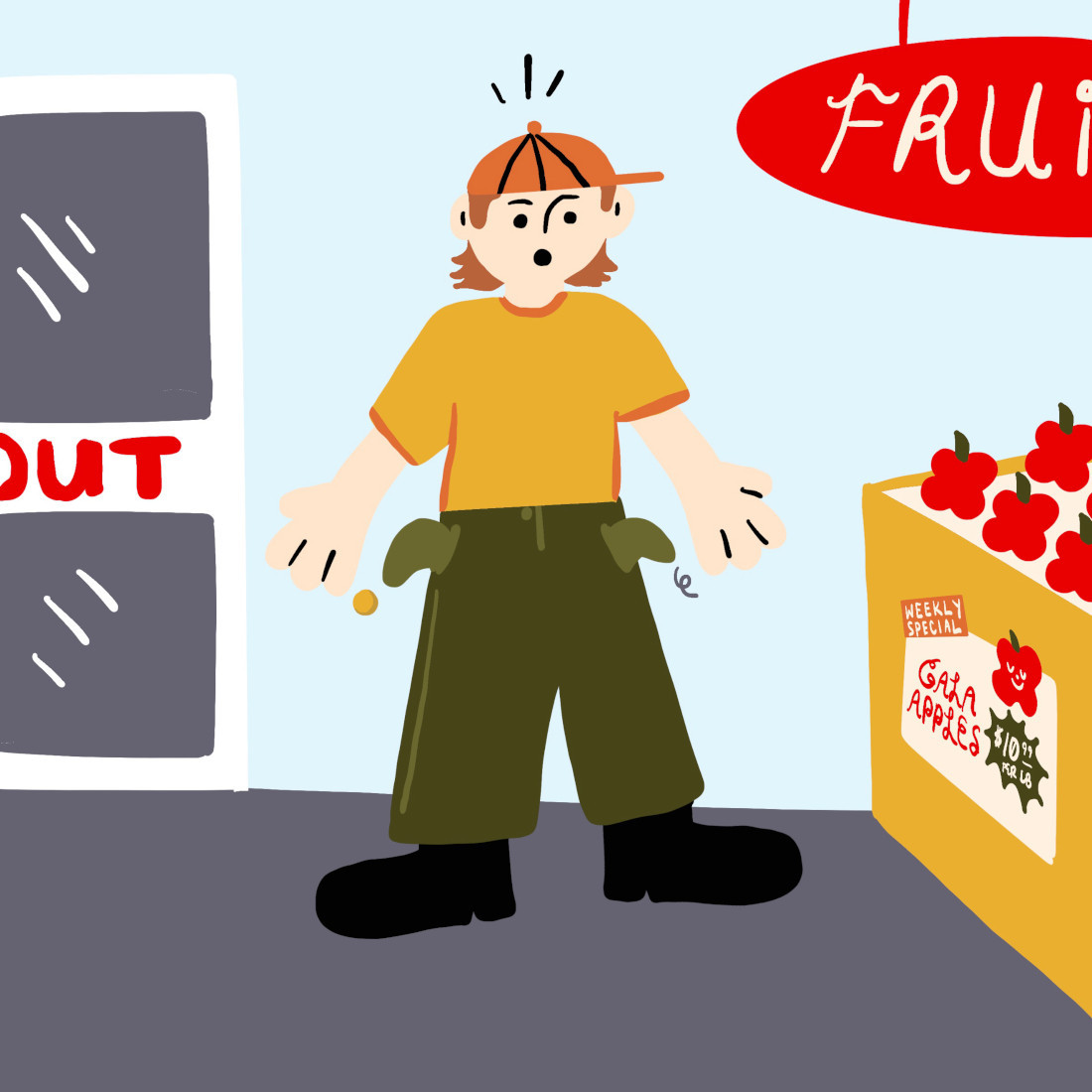

This inflation also impacts university students, whether they live on or off campus and whether they are domestic or international.

Tuition? Food? Gas? Oh my!

“I can obviously see the effects on my parents,” she says. “Just like the daily sort of things that they buy: groceries and gasoline and all that kind of stuff. I don’t know if it affects me personally as much. First of all, I don’t own a car, so I actually don’t buy gasoline, and I also eat food at home, so I’m very privileged in that sense.”

Another student who lives off campus, Senna Sedik, says she is not able to use cars as often due to the rising gas prices.

Fathma Mehjabin, an international student studying economics and living on campus, says recent inflation has definitely affected her cost of living.

“When it comes to groceries and everything, it’s much more expensive. Even the petrol prices are much more expensive. As a student, it’s hard to travel to different places, because you can see that the Uber prices have gone up. So, in general, transportation is harder.”

Chhavi Dhir, another international student, says there have been recent changes to her food expenses due to inflation.

Many of these students, if they could positively change at least one aspect of the recent inflation, would fix the surge of fuel costs in order to improve their ability to travel around the city.

The history of recent inflation

Philippe Cyrenne, a professor of economics at the U of W, speaks about recent inflation, where it comes from and what the government can do about it.

“You have to go back a little bit during the COVID period,” he says. “There were lots of issues with lots of plants, particularly when it came to the packing plants. But also, a lot of suppliers in the agricultural sector were affected by COVID, so I think many of the plants were operating below capacity.”

In regards to if inflation rates will stabilize soon, Cyrenne says “it all depends what the Bank of Canada is going to do.

The one thing that has happened during the COVID period ... largely, I describe it as sector-specific recession.”

Cyrenne specifies that income groups who had public jobs were affected by the recession, as public restrictions locked them out of their jobs. The federal government created the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) program to help those affected by public lockout.

Cyrenne says the issue with CERB was that it was the result of the federal government creating debt instead of borrowing money from the public or taxing citizens. Because the government created money from nothing, it caused inflation.

“So, in some sense, the inflation we see now is the legacy of those decisions made during the COVID period ... I think that most economists realized that there was going to be some reckoning that would take place after the COVID period.”

Cyrenne says there’s not much the provincial government can do to help its citizens.

“They don’t have the same resources that the federal government has. So, if you look at the budget of most provincial governments, they’ve all been in the red significantly for quite a while.”

But the provincial government does control university funding, an expense that directly affects students. Dhir expresses concern at the U of W’s high tuition fees and other student expenses.

“We don’t have U-Pass,” she says. “It’s just dollars (difference). But when you count those dollars for a month, it’s a pretty huge amount that you’re paying.”

She also believes the university should provide better accessibility services, as well as more basic student needs, such as printing services and food access.

Cyrenne clarifies that the sector-specific recession that occurred over the pandemic didn’t affect everyone, and that those who were able to work safely from home when the government placed public restrictions were able to avoid negative penalties to their income. He says the people who worked on the frontline or in jobs that they could not do remotely needed government support the most.

Supply and housing

Dr. Manish Pandey is a professor of economics at the University of Winnipeg. (Supplied photo)

“Inflation was rising even before the war,” Pandey says. “The discussion around inflation before Russia invaded Ukraine was about supply-chain disruptions, demand rising post-COVID and other logistical issues that companies were facing. Demand was rising, supply was not rising enough, and so you had this mismatch, and so prices were increased.”

But this mismatch was only supposed to be temporary, Pandey says. Once supply chains caught up, prices would return back to normal. However, the war on Ukraine was not something anyone could foresee, causing unexpected impact to inflation. The combined effect of oil prices rising and supply-chain disruption from the pandemic caused a large amount of inflation.

“Everything will depend on how quickly gas prices will adjust,” Pandey says. “It all depends on whether the open countries increase production right now.”

He says American oil cannot ramp up production, because these oil companies cannot dig shale oil that quickly. He acknowledges that Middle Eastern countries will have to take the brunt of the new demand, because they can easily ramp up supply.

“Housing-price increase is a source of inflation. But that is related to low interest rates in Canada, which the low-interest rate regime is now gradually changing to increases in interest rates to cool off the housing market,” Pandey says.

He says the effects of inflation wouldn’t be bad if not for the difference between inflation growth and income growth of working individuals.

“There is always a mismatch in terms of income growth and price growth, right? Incomes are not going to grow as fast, because there’s always a lag for income to catch up to prices. In real terms, we’re basically all taking a hit in terms of what our earnings are going to be.”

The passing storm

Philippe Cyrenne is a professor of economics at the University of Winnipeg. (Supplied photo)

“Most importantly, you can see the price of gas ... I think it has affected (the) majority of us right now due to this war in Ukraine.”

Another student, Jonas Yu, says gas prices are ludicrous, and fuel costs stack up quickly when traveling to and from the university.

“Even (inflation) goes through everything as a student. Even food ... Everything’s been going up,” he says.

It is not all doom and gloom, however. Pandey says Canada’s economy appears to be fairly good compared to other G7 countries. He states that Canada has gone back to pre-pandemic employment levels, and that the GDP has stabilized and is growing fast. He also believes that this year’s GDP growth should bring Canada back to where it should have been if the pandemic had not happened.

Cyrenne agrees that there are positive aspects.

“Well, I think the good thing is we’ve made it through the COVID period alive in some sense,” he explains. “So, to say I think the worst is behind us ... I mean, the governments themselves have to take a great deal of care to manage this transition from the COVID period ... But I think recent statistics show growth is coming back. And the reason that growth is important is that growth generates the tax revenue, which allows the support for individuals.”

Published in Volume 76, Number 23 of The Uniter (March 31, 2022)