I Am Not Your Negro

Plays at Cinematheque Feb. 28, 6 and 9 p.m.

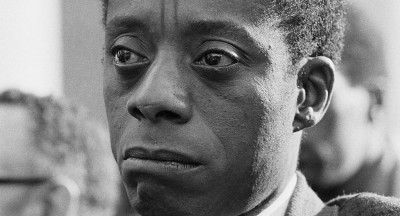

When the novelist, playwright and essayist James Baldwin died in 1987, he left behind an unfinished manuscript titled Remember This House. Baldwin’s premise for the book was to tell the story of America through his memories of his three murdered friends: Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X.

Those unfinished pages are the basis for the Oscar-nominated documentary I Am Not Your Negro. Directed by Raoul Peck and brilliantly narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, the film uses Baldwin’s words to examine race relations in America, both in Baldwin’s time and the current day. Peck provides that modern commentary, not by altering Baldwin’s words, but by using images that place the crises of 2017 in historical context.

Other documentaries that use dramatic readings of a book as their basis (The Kid Stays in the Picture, for example) usually feel less like movies than illustrated audiobooks. Peck never falls into that trap. His images don’t merely accompany Baldwin’s words. They elevate them by treating them with the appropriate respect and dignity, so as to make it difficult to imagine the words without the images, or vice versa.

Still, Baldwin always remains the star of the picture. His words manage to strike multiple notes at once. The film is both memoir and political essay. Even when describing historical events matter-of-factly, his writing is poetry.

He discusses scenes from a number of Hollywood films in terms of race relations, but these passages also function as brilliant film criticism. It illustrates that Baldwin’s literary legacy is vastly underserved and he deserves to be named alongside Mark Twain as one of the all-time great American geniuses.

The film also illuminates the ways in which Baldwin’s legacy has been tailored for white audiences. The popular image of Baldwin as a mid-20th century New York intellectual in the vein of Mailer or Capote, or an American expat in France à la Hemingway or Stein, has in some sense minimized his deeply passionate commitment to fighting for black rights.

The Baldwin onscreen here isn’t a piece in the larger puzzle of white literature. He’s on the frontlines with King, X and Evers.

One aspect the film doesn’t touch on much is Baldwin’s role as a gay rights pioneer. This is likely because Baldwin himself doesn’t touch on it in what survives of Remember This House. Peck finds other ways to explore this, including FBI memos detailing the Bureau’s surveillance of Baldwin and their plots to out him as a gay man. Baldwin does, however, examine Hollywood’s attempts to desexualize black men, pointing to the often chaste characters portrayed by Sidney Poitier. It’s a reminder why a film like last year’s Moonlight still feels so revolutionary.

I Am Not Your Negro, too, feels revolutionary. Its questions about race relations are as relevant today as they were half a century ago. Baldwin discusses his friends X and King, ideologues on opposite poles of their movement, arriving at the same place at the times of their deaths. His humanism always informs his message of empowerment. His nuance never negates his passion.

Published in Volume 71, Number 20 of The Uniter (February 16, 2017)