Fighting for transparency with freedom of information

Prison Pandemic Papers freeing correctional facilities’ COVID-19 data

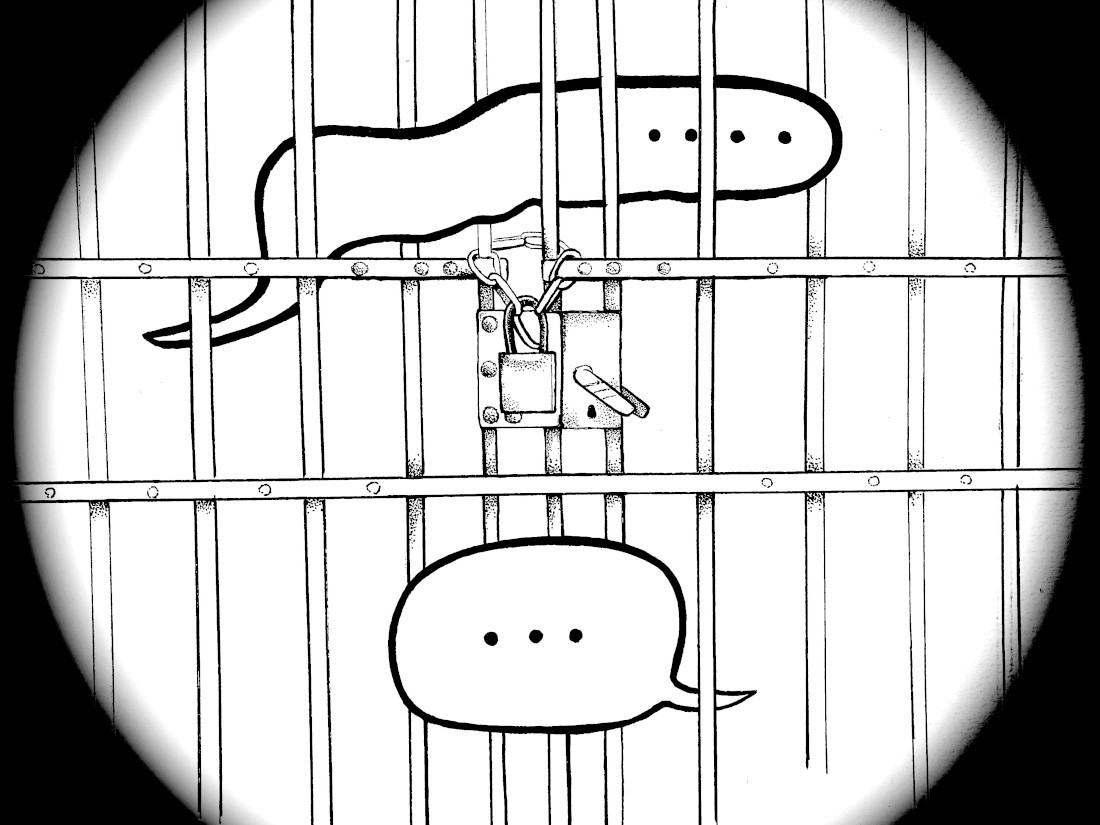

Illustration by Gabrielle Funk

The Prison Pandemic Papers research project used freedom of information requests and data science to obtain information about the state of COVID-19 in prisons over the course of the pandemic from provincial and federal bodies. The papers are now hosted on the University of Ottawa research website through the Criminalization and Punishment Education Project.

Kevin Walby, associate professor of criminal justice at the University of Winnipeg and director of the Centre for Access to Information and Justice, led the document collection. The centre undertook the project because people with loved ones in prisons were alarmed at the lack of information and communication coming out of prisons during COVID-19 waves.

Wren, an organizer with Bar None Winnipeg, says “(prison) case numbers are only coming in as summaries, when (authorities are) divulging anything.”

Bar None is an abolitionist prisoner solidarity group that coordinates rideshares for people visiting people in prisons. The rideshare program has been hit hard by the pandemic, and Bar None has diverted funding for rideshares to pay for calls to people in prisons, which are expensive.

The pandemic “really highlights the fact that prisons are always a public-health crisis. It doesn’t matter if there’s a pandemic or not. There are really poor health outcomes for people,” Wren says. “Ableism is really present in the way that we disappear people who don’t fit neatly into our systems into prisons.”

Walby says one aspect of the project he found most interesting was the shift in response to complaints from prisoners and grievances from prison staff.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, prison and jail authorities responded to those concerns by decarcerating,” he says. “They let people out of prisons and jails in quite a lot of jurisdictions across Canada, Manitoba included. There were hundreds of people released federally and provincially, and there was no big spike in transgression like some conservative pundits would surmise.”

Complaints and grievances regarding hygiene in prisons continued, and, in later waves, authorities did not decarcerate.

“That was one of the most shocking findings for me, I think,” Walby says. “Prison authorities showed that they can decarcerate, they can not throw everyone in jail, and they can come up with community solutions. They can have community sentences where people are close to their familial networks and can be supported and also not be stuck in a congregate setting being coercively exposed to a deadly virus.”

While some jurisdictions were relatively forthcoming with their data, Walby says the Government of Alberta used all kinds of tactics, such as excessive fees and weird time extensions, and gave out almost nothing. The provincial governments of British Columbia and Nova Scotia used similar tactics, but the research team was ultimately able to extract more substantial records from them.

Walby sees this project as a “model for how research can be done in a way that spans boundaries and brings people together.”

“A lot of times, research is very proprietary: ‘This is my data, and no one else can even see it,’ and I think with this project, we’re really trying to show that sharing data, creating some links and connections is a good thing, and research can help facilitate that,” he says. “Anyone should feel empowered to use freedom of information. You don’t have to have a PhD or be a journalist.” The centre offers training to those who would like to learn about doing research through freedom of information requests.

For more info on the Prison Pandemic Papers, visit bit.ly/372MdoI.

Published in Volume 76, Number 23 of The Uniter (March 31, 2022)