Feeding diaspora

Recipes as love letters

“Food is a time machine.” These words by Suresh Doss have been echoing in my mind since listening to Episode 63 (“Eating our way through Toronto”) of the Racist Sandwich Podcast. “It’s a conduit to a certain time and place,” he says.

Food is story. Every Lebanese recipe I learn from my mother is distinctively hers. My eagerness to record her recipes – and in a way, to archive her body memory – is also my longing and curiosity for her Lebanon.

It wasn’t until my final year of women’s and gender studies that I picked up work from Chandra Talpade Mohanty in Dr. Sharanpal Ruprai’s class. Feminists talk a lot about the politics of identity and locating oneself. Mohanty’s concept of social location and the temporality of struggle furthered my understanding of identity as the tangible crossroads between history, geography and time.

The food knowledge and cultural knowledge passed down to me is time-stamped. What this means as someone who has never visited my homeland and is disconnected from the Arab community locally, is that my cultural identity felt even narrower with Mohanty’s concept in mind.

Basing my arts practice in food the last couple of years has been a wonderful way to ground my work in lived experience and intergenerational inheritance. It has been a way to open dialogue with my mother and family and importantly, a jumping-off point for further research.

My world opens when I record one of my mother’s recipes. I feel secure in knowing that I will be able to recreate her dishes in my own home, offer loved ones the gracious hospitality that I have learned from her and continue to make those dishes for my own children one day.

Art and culture writer Aruna D’Souza wrote about food and memory in an Edible Hudson Valley article. “We ate our parents’ translations of their memories of childhood; our children eat our translations of our parents’ memories, translations twice removed. As a consequence, we change the places we arrive at as we grow our new roots. And as time passes, a curious thing happens: the places we come from change in reality, even as they stay the same in our memories, just as a parent looks at her grown daughter and sees the child she once was.”

D’Souza probes us to understand recipes as translations. In doing so, we are both honouring the recipes’ roots and acknowledging their malleability. This grounded fluidity is open to interpretation, but even with an attempt at rigidity, authenticity will always be unachievable. This doesn’t have to be bad news.

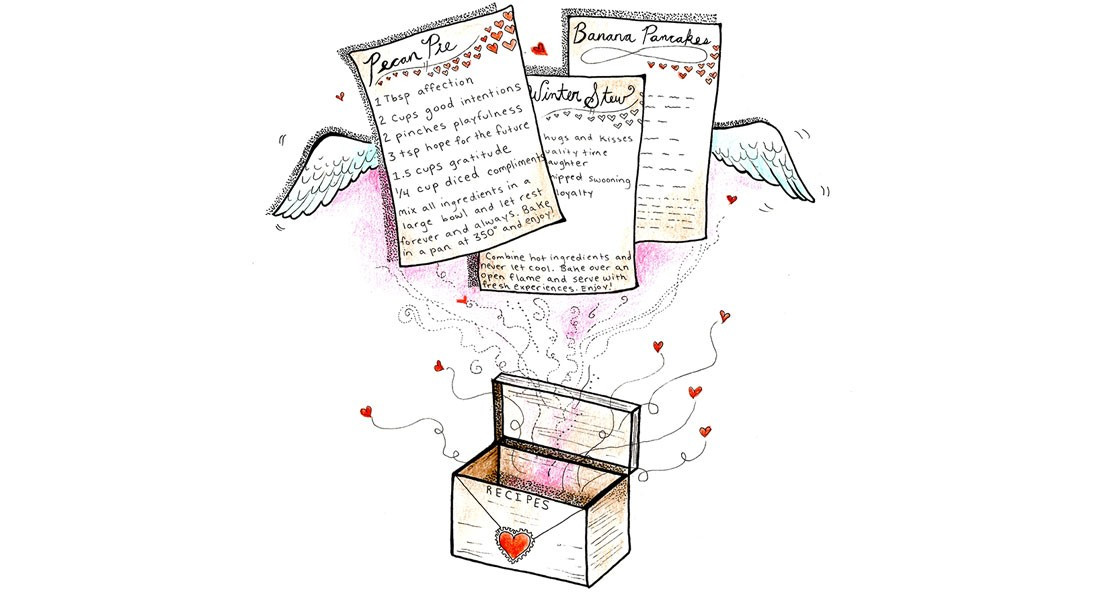

This is the pleasure of diaspora. Recipes are love letters in the way that they carry history and intention, but also a willingness to be imbued with new meaning – time-stamped, but ever-shifting.

“Food is how the dead talk to the living,” Armenian-American journalist Liana Aghajanian says in her blog Dining in Diaspora. Recipes are love letters passed down through generations. They are an attempt at translating a body archive or muscle memory for the sake of another’s nourishment, connection and pleasure.

The translation of body to page, and back to body, is the crux of how both love letters and recipes communicate. Food is a love language of the body. Cooking then, is the ritual of both a planned and spontaneous symbiosis between ingredients, places, bodies and intentions. It is always inherently connected to identity. It is always inherently relational.

Christina Hajjar is a first-generation Lebanese-Canadian pisces dyke ghanouj with a splash of tender-loving rose water and a spritz of existential lemon, served on ice, baby. Catch her art, writing and organizing at christinahajjar.com or @garbagebagprincess.

Published in Volume 73, Number 22 of The Uniter (March 21, 2019)