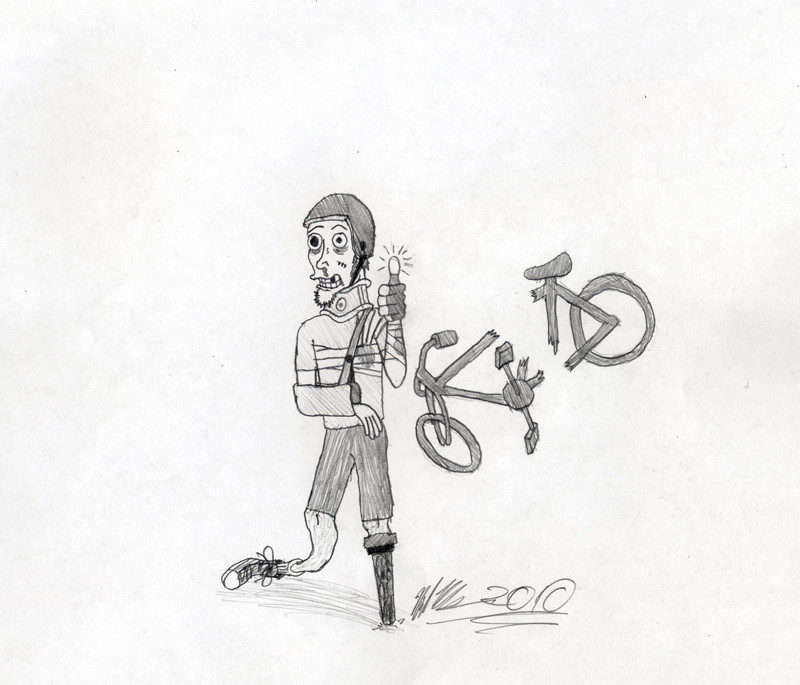

Cycling safety not a top-down issue

Educating cyclists on safety would be more helpful than making them wear a helmet

Bike lanes are a hot item in Winnipeg. Even though sustainable transportation hasn’t had the role in the civic election campaign that many hoped it would, it is hard to overlook the large amount of money currently being spent on cycling (coupled with pedestrian) infrastructure.

The current figure stands at $20.4 million of dedicated bike lanes and cycling routes to be added to the city’s active transportation network by the end of October. Large swaths of Dakota Street, Lagimodière Boulevard and Assiniboine Avenue, amongst other popular routes, either have recently been or will soon be converted to bike lanes or boulevards.

Over the past few summers, the bike path along Bishop Grandin Boulevard was completed, as were designated boulevards and “sharrows” along Grant Avenue, and throughout much of the Exchange and downtown.

Hard data on usage will probably take a few years to gather, but as the city’s active-transportation co-ordinator Kevin Nixon stated this spring, the point of the new infrastructure is to give people choice in their transportation.

This is all well and good, though future plans should include extending cycling routes and paths throughout all areas of the city and linking them up in a sensible manner.

Yet, one major factor in giving people choice in their matter of active-transportation seems to have been glaringly omitted: how to go about navigating the new infrastructure in a safe and enjoyable manner.

Anyone familiar with cycling bylaws in Winnipeg knows that the city currently does not require cyclists to wear a helmet. There have been several instances where people, such as concerned parents and neurologists, have pressed for the city to introduce a bylaw that would make helmets mandatory for all those riding a bike.

The line of thinking often goes that because people, especially kids and teenagers, feel peer pressure to not wear helmets, then making it the law to wear one will help reduce brain and head injuries incurred whilst cycling.

While this thinking certainly has its merits, the more reasonable approach would be to offer all children (and adults should they wish) some opportunity to engage in bicycle safety education. Leaving it up to various forms of authority to look out for the safety of thousands of potential cyclists raises a few problems.

For instance, who would incur a penalty should a young person fail to wear a helmet? Would parents or guardians be fined for actions undertaken for actions done beyond their sight? And I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but the illegality of an activity does not stop peer pressuring aimed at breaking the rules.

What’s more is that injuries suffered to the cranium are not the only possibilities when cycling, nor are they the only dangers one faces.

Anyone who spends a sufficient amount of time on their bike will notice the degree to which many cyclists – young and old – put themselves and others in harm’s way through a variety of stupid manoeuvres, lack of attention to their surroundings and ill-preparedness.

Many motorists notice this behaviour too, and proceed to tell all the cyclists they know how out-of-control and bat-shit nuts people on bikes truly are.

At least some of this dangerous behaviour stems from a lack of any discernible bicycle safety education made available to current and future cyclists.

Many people are never taught what one can and cannot do on a bike, nor are they provided with information on how to deal with particular weather conditions, surface areas, or other helpful tips on how to bike without ending up injured or injuring someone else.

This information could be provided to students at the elementary school level, much the same as bus ridership education is given now.

Nothing grandiose is being proposed here either. Spending an hour every school year with each grade is not asking for the moon. It could even be incorporated into gym classes.

Granted, it would involve the city and province working together to plan and provide such education, but with the new motivations open to Winnipeggers who wish to cycle, the city owes them the ability to become familiar with ways of doing so properly.

Community clubs could be used as sites under municipal jurisdiction where instruction could be given to adults who wish to bone up on their cycling knowledge.

If the city wishes to give people the choice to be active in their transportation, they should also give them the ability to do so safely and responsibly.

Andrew Tod is a politics student at the University of Winnipeg.

Published in Volume 65, Number 5 of The Uniter (September 30, 2010)