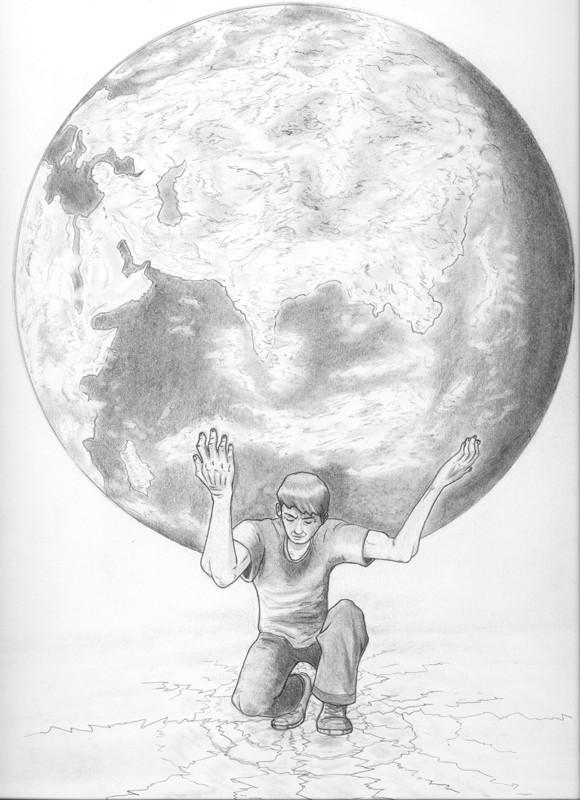

Crushed by the weight of the world

Why do we procrastinate?

Procrastination pervades our lives. It affects our everyday plans with our friends as well as our most crucial, life-changing decisions, often harmlessly, but sometimes with devastating results. This invisible force threatens the very survival of our species and many others besides, but it continues still.

This week, The Uniter looks at procrastination and its different impacts on different lives.

Melissa Gerbrandt is a procrastinator.

The 21-year-old University of Winnipeg education student will put off just about anything until the last possible minute, a tendency that has gotten her into trouble.

“My boss had to talk to me because I was always two minutes late for work,” Gerbrandt says. “I would procrastinate on leaving.”

Gerbrandt says her procrastination has two stages. It starts with the assumption that there is more than enough time to do the given task, which justifies her decision to instead watch TV or work on a different task.

Then, as the assignment due date or appointment time approaches more quickly than expected, the challenge skips straight from no problem at all to such an overwhelming one that productivity again suffers.

“I could accomplish a lot of large tasks, because I do have the time,” Gerbrandt says. “But because I procrastinate so much I then don’t have the time. And then it becomes too overwhelming to do, and I don’t want to start on it.”

Gerbrandt is very open about her problem. She’s not embarrassed to admit that her procrastination prevents her from living up to her fullest potential. Perhaps the worst part is that she can’t even enjoy the leisure time she creates.

“There’s always that nagging voice in the back of my head,” she says.

Melissa’s situation reflects a common reality for many students.

Dr. Dan Bailis, a professor in the University of Manitoba’s psychology master’s program, says that procrastination is a natural response to looming papers and exams.

Natural doesn’t necessarily mean positive, though.

“Students often procrastinate in ways that look like effective problem-solving, but aren’t really,” he says.

However, putting off challenges isn’t always a purely bad thing.

“It can be part of choosing which goal to pursue, or by which means, when several options are available,” Bailis says.

The human approach to all problem-solving is fundamentally the same in any given situation, Bailis says. There is a period of assessment followed, ideally, by the necessary action to improve things.

Even when the procrastination seems completely irrational and without direct consideration of the challenges at hand, it can be part of the assessment phase.

“We all have systems for coping with an inner world of identity and emotions on one hand, and an outer world of problems and opportunities on the other,” Bailis says. “The two systems are more independent than most of us realize, and sometimes one hand helps the other, so a gradual approach might allow us to face a challenge that would otherwise be too much to bear all at once.”

Life and death?

What about when the stakes of a looming challenge are no longer a matter of grade points, but rather a matter of life and death?

Lori Santoro, a nurse educator at the Cancer Care Manitoba Breast Cancer Centre of Hope, says that people who suspect they may have cancer may not immediately seek treatment for a variety of reasons.

“Life’s too busy, they didn’t think it was anything serious, cancer doesn’t run in their family, too much stress,” Santoro says. “Sometimes it’s fear of the unknown or fear of it being too serious. Sometimes they know other people’s horror stories. They don’t realize that everyone’s experience is different.”

In a 2008 U.S. national study of cancer survivors, more than 50 per cent of respondents said they had waited more than two months to see a doctor after discovering cancer-like symptoms. Of those who waited, 80 per cent cited fear or procrastination as their reason.

Even after diagnosis, a very small number of people choose inaction rather than treatment.

“Some people say, ‘OK, tell me what I need to do and let’s get at it,’” Santoro says. “Other people will retreat into themselves. They’re almost paralyzed by overwhelming anxiety.”

Santoro uses a gentle process of education and support to help people make the best decisions for their specific situation, but the overwhelming struggle associated with what Santoro calls the “c-word” can be debilitating.

While Bailis says that people are more likely to take risks and face a challenge when the perceived outcome is certain loss, the hopelessness of illness can still override self-preservation.

“Sometimes people are angry or upset and feeling, ‘What’s the point? I’m going to die anyway,’” Santoro says. “It still shocks them to their core.”

It might seem crude to compare schoolwork and cancer, but when it comes to traversing a challenge, everything is relative.

“Size doesn’t matter,” Bailis says. “The same factors seem to predict procrastination across studies that have looked at relatively near-term, specific and controllable academic challenges, or relatively long-term and uncontrollable health-related challenges.”

One major difference between an approaching university exam and the fear of a serious medical diagnosis is that people usually choose to attend post-secondary education while no one chooses to face cancer.

“People engage with self-determined challenges in a more positive and productive way, compared with challenges that are not self-determined, which might be perceived instead as obligations, strong situational demands, or even threats,” Bailis says.

Procrastination and climate change

This is where it becomes interesting to look at a challenge common to every single person on Earth: global climate change.

There are few problems with a more certainly negative outcome, and no other challenge that will have results on such a wide scale.

Anika Terton, public education and outreach coordinator with Winnipeg-based Climate Change Connection, recently spent time in Durban, South Africa, as part of the Canadian youth delegation at an international climate change meeting.

“Many people had really low expectations, and to be honest Durban was really close to a failure,” Terton says of the meeting.

Despite achieving what Terton describes as the best outcome possible given the political forces involved, the treaty reached at Durban still settles with a 4 C global warming by the year 2100, which would have catastrophic effect on sea levels worldwide.

How is it possible to fail when the price for failure is so dear?

Part of it, no doubt, is the collective nature of the challenge. The assessment period of the problem-solving process drags on because people aren’t sure about the science.

“People look to each other’s reactions to determine whether a given situation is indeed a problem,” Bailis says.

Terton acknowledges that confusion does harm the climate change cause, but she refuses to believe that this is an accident. After decades of study, the science is indisputable, she says, and any remaining doubt has been manufactured.

“When we found out that the only way to deal with this problem is to change our lifestyles, that’s when the problem became overwhelming,” Terton says. “Industry started to put a lot of effort into public campaigns and using uneducated people who don’t know much about climate science to spin the topic and dumb it down. They were using any kind of doubt and any climate scientist they can pay to say the opposite.”

All this contrived confusion seems to have cooled Canadian media consumers to the climate change topic. A recent Toronto Star survey of five major Canadian daily newspapers found that there were approximately 2,500 total occurrences of the phrases “global warming” and “climate change” in 2011. That’s down from 7,000 mentions in 2007.

Even for those people who accept that climate change is a real danger, the facts can cast a dismal shadow on the potential for action. With a global population expected to near nine billion by the year 2050, fossil fuel consumption seems bound to expand drastically.

“I think that a lot of people feel like, ‘It doesn’t matter if I change, it doesn’t matter if I recycle my bottle, because the rest of the world is still going to use a lot of water bottles,’” Terton says.

But while these facts lead to despair and stagnation for some, Terton remains optimistic that this picture can change. She says that developed nations need to utilize clean energy solutions to support those nine billion people.

“We have the financial resources to make the first steps,” she says. “If we look at all the subsidies worldwide that we put into fossil fuels, and if we cut off these subsidies and put them towards renewable energy, the picture would look very different.”

In Canada alone, those subsidies total $1.4 billion just from the federal government. With the provinces added, the figure is $2.8 billion.

The question is do we, the people, have the power to shift our governments towards a sustainable future and away from the power of fossil fuel corporations?

“People feel helpless,” she says. “They’re looking at our government and asking why there isn’t more happening. Why aren’t we addressing the problem? Why don’t we have an adult conversation about climate change?”

Unlike that pesky paper due next week, humanity cannot procrastinate any longer on climate change.

“Climate change is not just an environmental issue, it’s a social and economic issue,” Terton says. “It’s a justice issue, which we have to address when we talk about it.”

Published in Volume 66, Number 25 of The Uniter (March 28, 2012)