Confronting consent

Students call to update Manitoba’s sexual-education curriculum

High-school students are calling on provincial and territorial governments across Canada to make comprehensive education about sexual violence, relationships and consent part of health curriculums.

“Sexual assault should not be a high-school experience,” read a protest sign from Alexandra. The 16-year-old rallied at the British Columbia legislative building in April and is part of the @vic_against_sexualassault Instagram group.

High School Too, another student-led organization, is advocating to end sexual violence within schools and strengthen conversations about consent across Canada. This student group was started by the Consent Action Team at Toronto Metropolitan University.

High School Too aims to amplify student voices, collaborate with existing community organizations and implement education programs that address sexual violence, sexual-harassment policies and consent.

According to Statistics Canada, there were more than 34,200 police-reported cases of sexual assault in Canada in 2021. This is an 18 per cent increase in reported cases from 2020.

Although discussions about sexual violence have become more prevalent, 63 per cent of survivors do not report to the police. Sexual assault is highly stigmatized and one of the most underreported crimes.

Outdated curriculums

The K-12 PE/HE curriculum overview identifies five major health risks, one of which focuses on human sexuality. Youth are supposed to learn about contraceptives, pregnancies and preventing sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs). The curriculums overview does not mention consent or sexual violence.

The Manitoba Teachers’ Society recommends that the Manitoba government update school curriculum every seven years.

In 2019, Jason Fiedler, training institute facilitator at the Sexuality Education Resource Centre (SERC) in Brandon, sent a written submission to Manitoba’s Commission on K-12 education promoting eight recommendations on sexual-health education.

These recommendations include: using a comprehensive approach to teach consent, pleasure, rights and harm reduction; starting sex education before Grade 5; weaving the curriculum throughout the year; ensuring every student across the province learns about sexual health; decolonizing the curriculum; reflecting on sexual, gender and relationship diversity; addressing gender-based violence and power dynamics; being culturally safe and trauma-informed.

In this document, Fiedler says, “Rather than solely discussing the risks of STIs and pregnancy, comprehensive sexuality education discusses the relationships involved in sex and celebrates the positive and pleasurable aspects of why people have sex. Discussing both pleasure and protection is a human-rights and consent-based practice.”

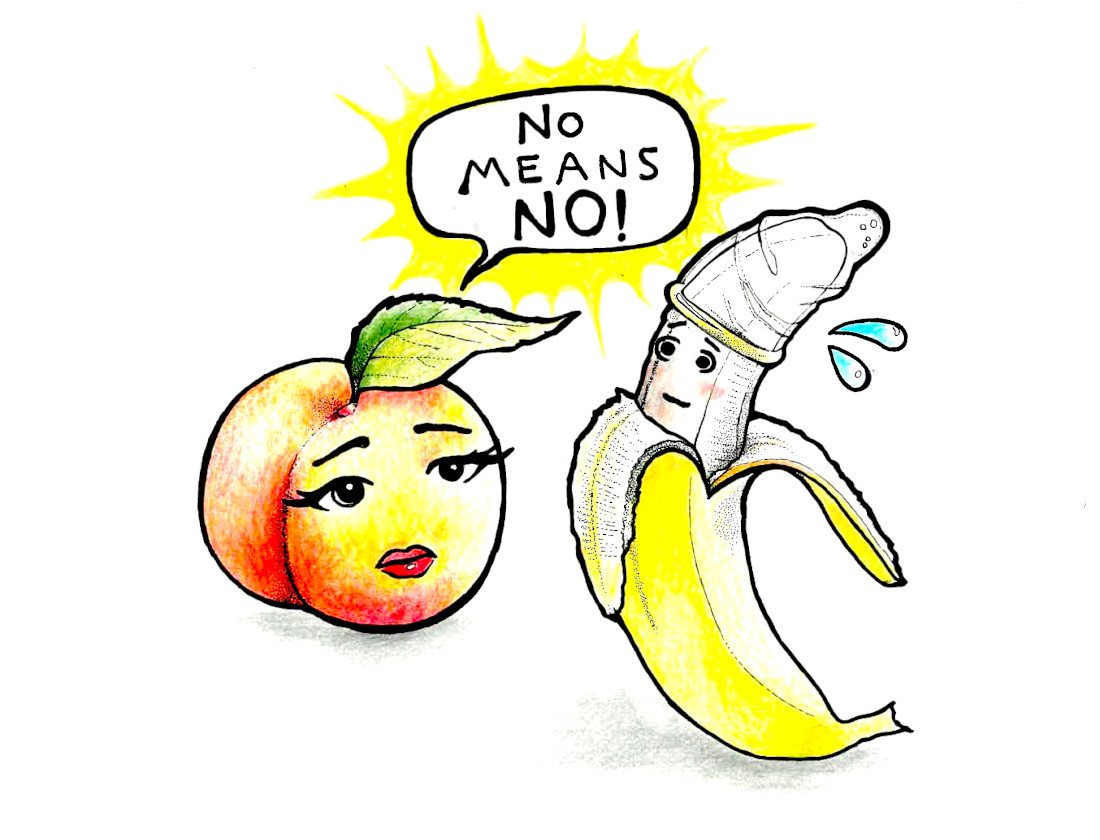

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Leigh Anne Caron, executive director at SERC in Winnipeg, observed facilitators engage with classrooms about consent. She says the fun, interactive presentations helped students quickly understand the topic. There’s always some giggling, but games allow students to identify what is or isn’t consent.

“When language like bodily autonomy, rights, choice and consent starts young, it gives kids the tools to be able to have autonomy over their bodies, to have those conversations and know that they have rights and can say no and can come and talk to a trusted adult,” Caron says.

She also says there is research supporting sexual education that moves beyond topics like preventing pregnancy or STBBIs. Deeper discussions can help students learn about and appreciate sexual diversity, Caron notes. These lessons can also help students feel safer, develop healthy relationships and learn communication skills.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted student learning around sexual health, which, in some cases, wasn’t taught for two years. To avoid inconsistency on teaching consent and sexual education, Caron says these topics need to be addressed before Grade 5 and woven throughout multiple subjects and classes during the year.

Isabel, now a Grade 9 student at John Taylor Collegiate, says she did not learn about consent, birth control or safe and pleasurable sex when she attended St. Charles Catholic School.

The teachers “told us that we don’t need to talk about that, because you won’t have sex until you’re married,” she says. “I feel like it would be beneficial if students knew about the pleasure aspect of it instead of just being told ‘don’t (have sex).’”

Who are we excluding?

The current K-12 PE/HE curriculum addresses building and maintaining healthy relationships, but it does not discuss sexual harassment, assault, rape or abuse.

The latest Child and Youth Report in Manitoba shows that 17 per cent of sexually active Grade 7 to 12 students reported having sex when they did not want to. In addition, the Canadian Women’s Foundation reported in 2018 that only 28 per cent of Canadians fully understand the meaning of consent.

Isabel thinks students could benefit from having conversations about consent in the classroom.

“I’ve noticed that most of the female-identifying people are understanding of (consent), but guys, they think of it as a form of teasing,” she says. “They’ll do something, you’ll say no, and then they’ll just do it again because they think it’s a game or something.”

Although SERC teaches student workshops about consent, Caron says it’s difficult to appropriately address sexual violence when class sessions are short and students haven’t yet had foundational conversations about safer sex and consent.

“We make sure that we give the tools, resources and information (to teachers), so that if somebody did need to disclose something, they have a way to do that now,” she says.

Sixty-four per cent of transgender and gender-diverse students report feeling unsafe at school due to harassment, bullying and sexual assault.

To help support 2SLGBTQ+ students, the sexual-health curriculum should use inclusive language that reflects sexual, gender and relationship diversity, Fielder says. “When sexuality education only discusses cisgender, heterosexual, monogamous relationships, we are perpetuating disrespectful and unsafe environments for all students.”

Caron says many factors affect if or how sexual education is taught within a school. In certain settings, students may feel unsafe coming out or being openly sexually active. “It depends on the school, and it depends on the culture,” she says.

Organizations like the Survivor’s Hope Crisis Centre (SHCC) in Manitoba’s Interlake can help provide support, crisis-intervention services and educational resources for rural schools.

The SHCC’s Sexual Assault Discussion Initiative (SADI) program offers 65-minute workshops for middle- and high-school students about healthy self-esteem, gender, media literacy, internet safety, mental health, trauma, healthy relationships and sexual violence.

Changing the narrative

Fiedler says Manitoba needs to decolonize the curriculum and include resources to support Indigenous students.

For example, the Child and Youth Report said that “in 2014, 12 per cent of Indigenous youth age 15 to 24 reported being victims of emotional abuse in a relationship, and 8 per cent reported experiencing physical/sexual abuse.”

To mitigate the risks that these specific communities face, the Native Youth Sexual Health Network engages with Indigenous youth and intergenerational relatives to teach reproductive rights; culturally safe sexual health; midwifery and birth justice; and Two-Spirit/gender and sexuality education.

Fiedler says it is also important that Manitoba provides culturally safe and trauma-informed training for teachers. Aside from SERC, which offers service-provider training and consultations, the Manitoba Trauma Information and Education Centre (MTIEC) provides trauma-informed training and webinars.

Students can access safe-sex supplies from the Women’s Health Clinic, Teen Clinic, Klinic Community Health and the Rainbow Resource Centre.

Based on the recommendations outlined in Manitoba’s Commission on K-12 Education, the Education and Early Childhood Learning department created a K-12 Action Plan that was released in April 2022.

Wayne Ewasko, Manitoba’s education minister, says this document “is pretty significant, and it’s going to drive all our work moving forward in addition to the document called Mamàhtawisiwin: The Wonder We Are Born With,” which focuses on Indigenous education and inclusion.

“Within the K-12 commission, they recommended that we do a review of the various different curriculums, and so when we did up the K-12 Action Plan, we included that we were going to do a review of the physical education and health education curriculum,” Ewasko says.

He says that later on in the 2022 school year, a pilot project will be launched to observe how students from selected schools in Manitoba respond to the recommended updates. If the pilot is successful, all schools will implement the new curriculum by 2023 or 2024.

However, it is unclear whether the K-12 Action Plan will shift toward a comprehensive, evidence-based approach and specifically include topics about consent and preventing sexual violence, among other recommendations from different organizations.

Sexual-health education advocates like High School Too encourage people to take action by writing to their school-board representatives and provincial, territorial and federal governments to ensure that comprehensive education about sexual violence, relationships and consent is a priority.

Published in Volume 77, Number 06 of The Uniter (October 20, 2022)