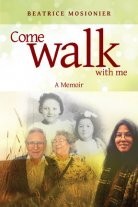

Come Walk With Me

If you went to junior high in Winnipeg, chances are you’ve read In Search of April Raintree and likely still remember it to this day. Beatrice Mosionier has vividly depicted the image of April and Cheryl’s plight, attempting to maintain their Native American pride while facing real-life problems as they try to survive.

The story, while fictional, could only have been produced by a woman whose life experience matched the message she so clearly sends.

In the autobiography Come Walk With Me, Mosionier exposes her personal involvement with foster family life, molestation, rape and the suicide of her sisters.

The book is divided in three parts, all centered on the theme of walking.

The connections between Beatrice and April’s lives are featured prominently throughout the respective books, although the literary exaggeration of April’s fictional experience in comparison to Beatrice’s actual experience is noticeable.

As Mosionier’s parents visit less and less, she struggles with the lack of love and support, which no doubt affects a child, but she retains a relatively normal childhood despite the circumstances.

Beatrice’s developing years are recounted most effectively in Come Walk With Me, as the literary style is childlike and open. But, as she matures into adulthood, the childlike tone persists and makes the emotional effects of the heavy content less potent.

She rarely describes how she feels about the outcomes of the seemingly endless tragic struggles she faces, and it essentially becomes a presentation of facts.

It mentions in the novel that she had no writing experience before April Raintree and it is glaringly obvious here.

Much ado is given concerning Beatrice’s difficult romantic situation, but the suicides of two of her sisters are barely touched upon.

The autobiography leaves the reader at October 1987, a full 22 years ago, and we are never certain if she has finally found happiness or if she has even overcome her past at all since.

One redeeming factor of the memoir is the addition of an interview with Beatrice’s mother, Mary Clara Pelletier Mosionier, before each of the three sections. It is a genuine presentation of the conflict she faced as an alcoholic and aids in humanizing the conception that the reader has of the absent mother figure.

There is no doubt that Mosionier’s message as a Native American woman has the potential to teach many generations about our preconceived notions concerning the “forgotten peoples,” but perhaps this subject could have been more deeply explored by another writer.

Published in Volume 64, Number 10 of The Uniter (November 5, 2009)