Bodies as burdens

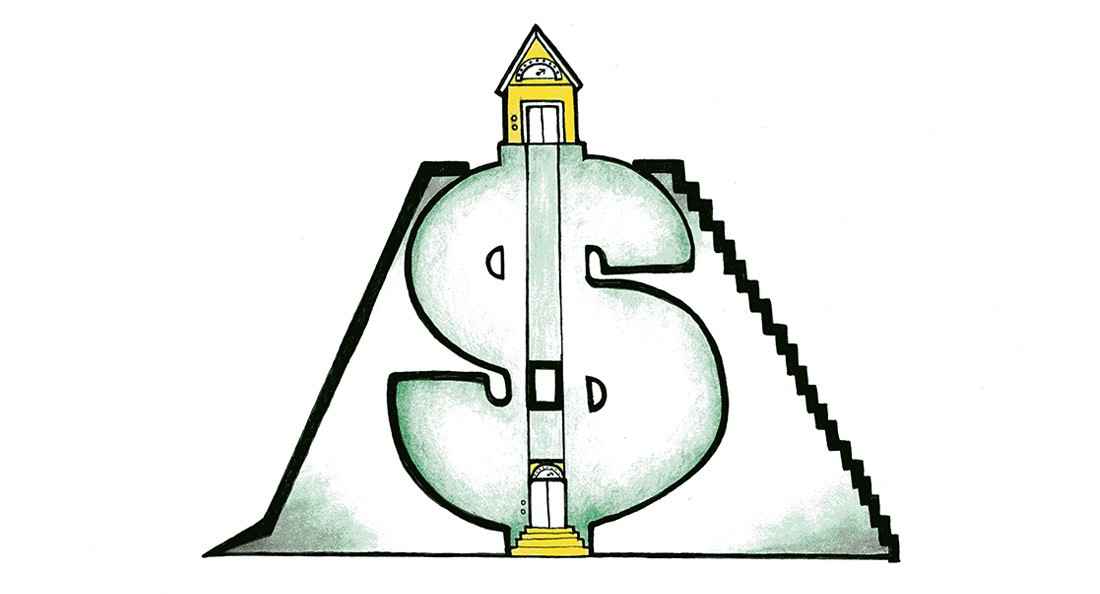

Crippling capitalism

Society has labelled persons with disabilities and neurodivergent people as burdens for the past several centuries. Neurodivergent people are folks who lie outside what is typically understood as normal mental functions or experiences. This has created a culture wherein persons with disabilities are twice as likely to be victims of violent crimes, where 83 per cent of women with disabilities experience sexual violence, where the most commonly reported act of discrimination in Manitoba is disability and where ableism is still considered widely acceptable.

Capitalism is one of the main factors contributing to the unjust labelling of burdens on persons with disabilities, as capitalism creates a society where worth is determined exclusively based on capital and labour.

Capitalism manifests in the way society views bodies and minds. Bodies and/or minds that are able to produce at the highest capacity possible are deemed well and are largely celebrated by society.

This is seen in the glorification of exercise culture in the Western world, where bodies that are able to produce labour to the highest degree are seen as the most desirable. Contrarily, bodies that are not able to produce labour in the same capacity, be it through chronic illness, pain or different mobility abilities, are seen as the least desirable and stigmatized.

Capitalism is the force behind understanding disabilities as burdens. Canadian Immigration Law refers to persons with disabilities as being an “excessive demand” on society, because persons with disabilities may access social services and may not contribute to economic systems in the same way as neurotypical, temporarily able-bodied people.

Neurodivergence, madness or experiences of mental illness are demonized, considered burdens and medicalized. Medication is administered often not to help with wellness, but rather in order to ensure productivity. Therapy and all forms of treatment are not meant to encourage understanding of neurodivergence, but rather in order to increase productivity, and are catered towards re-entry into the workforce.

It is easier for people experiencing mental illness to access medication than to access therapy or group therapy. Self-care is no longer about collectivity, but is now centred around individualization and is a largely individualized process.

Self-care in its current form is rooted in capitalism, where individuals are expected to purchase nail polish, clothes and gym memberships and be alone to feel better. Self-care currently is only celebrated because the main intention is for individuals to be rested enough to return to a hyperproductive state.

The recent Accessibility for Manitobans Act encourages accessibility exclusively because companies can increase profit by making their businesses accessible to persons with disabilities.

While it is beneficial for spaces to become more accessible to more people, it is discouraging that this act has been put into place only after research was released that proved that it is financially beneficial to have accessible businesses. While this act is a good starting point, its failure lies in the fact that it prioritizes capital over human beings.

Accessibility is about more than the ability to purchase. Disability rights are more than the right to consume, and bodies are worth more than their ability to produce.

Megan Linton is the current VPEA for the UWSA. She is a mad activist, sometimes seen clutching a cane, other times, clutching a sprinkled doughnut. You probably owe her a doughnut for unpacking your deep-seated ableism.

Published in Volume 72, Number 21 of The Uniter (March 15, 2018)