(Abuse of) power is a many-splendoured thing

Unravelling power and consent will take all of us

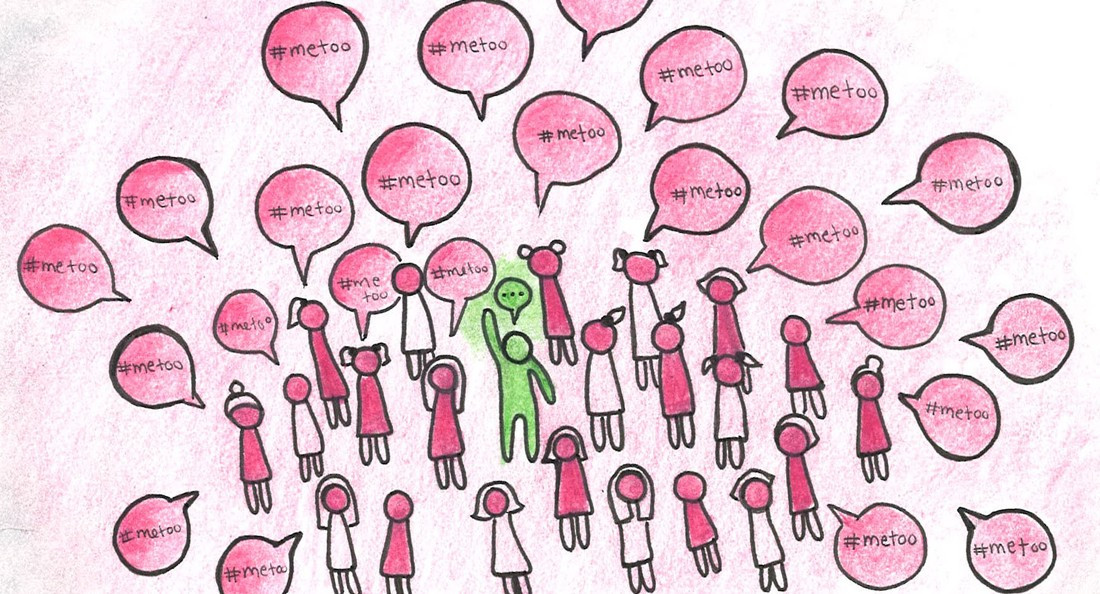

When news broke that NYU professor Avital Ronell and prominent Harvey Weinstein accuser Asia Argento had been accused of sexual harassment and sexual assault, respectively, many questioned whether their implication or culpability delegitimized the #metoo movement.

The question, how do we make space for harm done by those who have claimed harm, takes on a different (and pointed) dimension when asked about women who have allegedly harmed men.

In response, Tarana Burke, founder of the #metoo movement, reiterated that “sexual violence is about power and privilege. That doesn’t change if the perpetrator is your favorite actress, activist or professor of any gender.” Gendered and institutional power are both strands of the tangled knot of power that operates within, and across, relationships.

This emerging cultural conversation has been, from the beginning, about the complexities of those dynamics and how they interact to impact an individual’s ability to consent.

As that conversation gains traction, it also naturally expresses subletities and distinctions. Pitting one form against the other only dilutes this conversation of the nuance it so desperately needs.

Perhaps there is no better case study for the way institutional power reproduces than in the case of Avital Ronell. Found guilty of sexually harassing her grad student via internal investigation conducted at NYU, Ronell has been publicly backed by a glittering lineup of queer scholars and public thinkers who circulated a letter on her behalf.

That is, until Andrea Long Chu, a doctoral candidate and former student of Ronell’s, published a response titled “I Worked With Avital Ronell. I Believe Her Accuser,” unleashing a long festering conversation about academia’s complicity in abuses of power and intellectualism itself as a smokescreen for diminishing harm.

The searing essay illustrates that while Ronell’s behaviour is unprofessional and inexcusable, it is also not unheard of within academia, and, in fact, might be a product of a particular nexus of power and privilege. This is a problem. And one that the five currently open investigations into sexual assault, harassment and unspecified human rights abuses at the University of Manitoba only confirms.

What each new high-profile case has revealed is that we, as a society, do not know how to talk about power and how to extricate consent from its clutches. Maybe, in a deeply unequal world, we simply don’t know how to be with one another equitably.

Moreover, messy accountability processes and the court of public opinion reveal something deeply unflattering and ugly to behold: as long as we think no one is looking, many of us will take advantage of some measure of power, great or small, over another person. Hurt people hurt people. It is easier to retrace pain, and to rewind, than to figure out how to heal. Individually and collectively.

Nuance, context, position, identity, gender, age: these things matter. They factor in and help fill in the crude outlines of perpetrator, of victim. But, as Chu reminds us, “sometimes analysis is simply denial with more words.” We can’t stop at words or justifications. We can’t hide behind theory, or private pain. Sometimes the truth is simple. We have failed each other. We must be better.

Dunja Kovačević is the comments editor of The Uniter. Settler immigrant, critic, and somewhat-reluctant communications person, she is writing and thinking on Treaty 1 territory. Find her on Instagram and Twitter @kvirandnow.

Published in Volume 73, Number 2 of The Uniter (September 13, 2018)