A limited support system

Eating-disorder treatments, awareness and wait times

At the start of this month, Manitoba’s provincial government formally recognized Eating Disorders Awareness Week and announced plans to further fund local eating-disorder programs.

The Province will spend $224,667 on programs for children and adolescents at the Health Sciences Centre (HSC). The funding will be used to improve wait times and hire a nurse therapist and a social worker, who can support up to 80 more families each year.

Wolseley MLA Lisa Naylor worked in eating-disorder treatment before entering politics. She brought forward the Eating Disorder Awareness Week Act to help raise awareness.

“Now that it is declared, it puts it on the government’s radar every February,” she says. “I think that’s important when we look at future funding and having the government see this as an important issue.”

The Province has chronically overlooked and underfunded eating-disorder treatment programs, and some patients are sent out of Manitoba for care.

In 2021, a psychiatrist at HSC who specialized in child and adolescent eating disorders found that referral rates for teens seeking treatment tripled early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Susan Watson, a registered dietitian with A Little Nutrition in Winnipeg, says dramatic lifestyle and social changes can trigger disordered eating behaviours, as “eating is the one thing people feel they can control.”

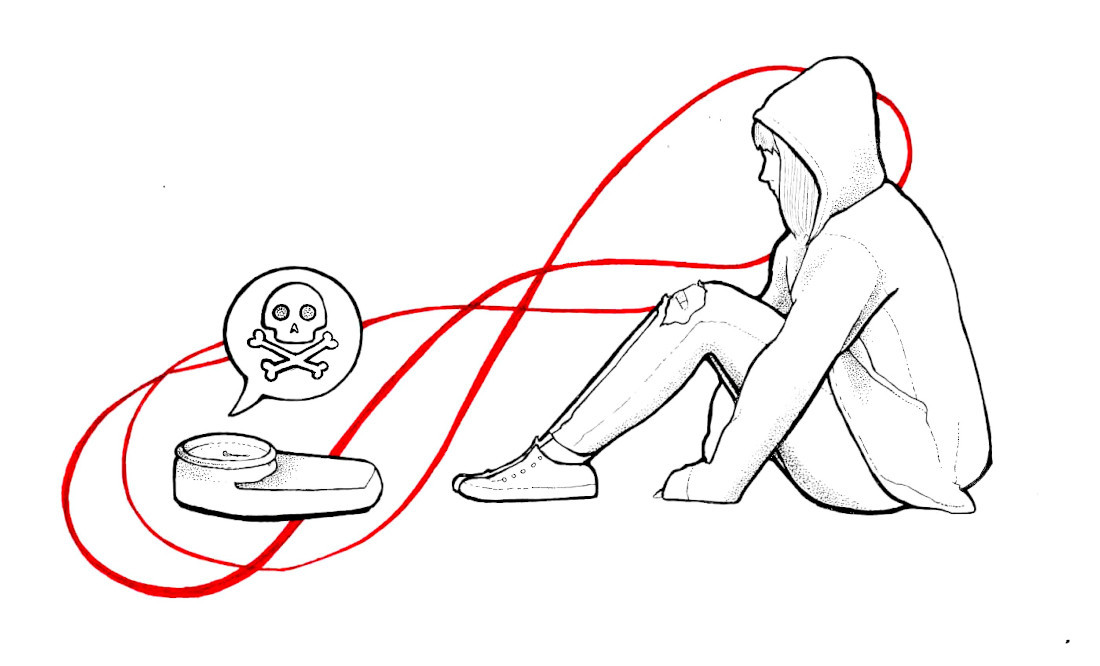

Isolation can further disordered eating, as those who feel shame related to symptoms or eating patterns may more easily keep their habits secret.

Watson works to help people living with eating disorders and educate about related biases. She says Manitoba offers limited support. Since Westwind Counselling closed in Brandon, there are currently no dedicated long-term residential eating-disorder programs in the province.

In Winnipeg, care options include HSC’s program for children, its Adult Eating Disorder Program and a provincial program offered for adults of all genders through the Women’s Health Clinic (WHC).

Wait lists for treatment programs are long. The WHC website says participants may wait between 18 and 24 months, and “some people may require more intensive treatment” before starting the program.

Naylor says she is concerned about people waiting for treatment. While the WHC attempts to stay in touch with those on their waitlist, she says the provincial government doesn’t monitor “how many people might die while they’re on a waiting list.”

Another problem is the lack of eating-disorder treatment programs in Manitoba’s North and rural regions. Naylor says it’s difficult for Manitobans to access services close to home, and many programs only operate in certain ways.

For example, she says, some people may benefit from full-time programs, while others only need to attend a weekly group and see a dietician or counsellor. “We need to have a better way of making sure the right people are on the right waiting list,” Naylor says.

Watson identifies another problem. She graduated from the University of Manitoba and says her program only devoted a few weeks to eating disorders, which may be because “eating disorders have always been considered a mental-health concern, not a nutrition concern.”

Really, they’re both. Eating disorders take many forms, and “people with eating disorders can be in any shape, size, body, gender, age and be very, very ill without people knowing,” Watson says.

Each person’s eating-disorder recovery will vary, but she says the process should involve a multidisciplinary team. This can include a family doctor, a psychiatrist or psychologist, a nutritionist and other community supports.

Watson is in the final stages of becoming a certified eating-disorder specialist with the International Association for Eating Disorders. Once certified, she will be the only practitioner with this designation in Manitoba.

She says it’s important that medical professionals of all levels are eating-disorder informed.

“We also need to have more training for all levels of healthcare to recognize the red flags of an eating disorder so that people don’t slip through the cracks,” she says.

“I think we could be doing a lot more to increase the capacity for all kinds of care providers around the province.”

Published in Volume 77, Number 19 of The Uniter (February 16, 2023)