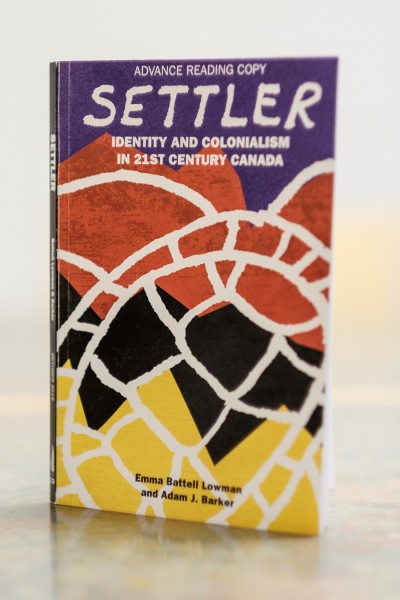

Settler: Identity and Colonialism in 21st Century Canada

Emma Battell Lowman and Adam J. Barker

145 pages

Fernwood Publishing

October 2015

Settler isn’t an easy read by any definition. It’s a dense book, one that’s intensely academic and intellectually provocative. It provokes many emotions, chief among them anger and guilt (usually intentionally, sometimes not). It’s thick with ideas that will fundamentally shake how many Canadians understand society.

The intention of the book is to examine the idea of settler identity. “Settler” is an identifier that distinguishes from indigenous peoples. It’s a complex term that authors Lowman and Barker flesh out extensively, examining the settler Canadian relationship to Canadian colonialism and how they can take steps towards decolonization.

The theoretical aspects of the book, which make up roughly 50 per cent of the text, are spot-on. The writers examine how past Canadian power structures of colonialism continue into those of today. They lay out how our supposedly post-colonial society continues to colonize, displace and discriminate against indigenous peoples. They also examine the inherent paradoxes in settler solutions to decolonization and how well-intentioned actions can continue to undermine indigenous sovereignty.

While taking to task modern right-wings like Tom Flanagan, Conrad Black and Stephen Harper, Settler also examines how leftist politics can discriminate while trying to bolster economy.

Essentially, they dispel the long-held myth that the problems of indigenous-settler relations in Canada aren’t, as they’re so often called, an “Indian problem.” They’re a settler problem.

These ideas won’t be new or controversial to anyone other than the willfully ignorant. This is why it’s troubling when the authors make ludicrous reaches to attempt to justify ideas they don’t really need to.

Most people will agree that the seizure of indigenous land to create Canada was unlawful. So, why do the authors of Settler try to justify that by calling the Bering Strait migration a myth? They question the scientifically accepted theory of the prehistoric settlement of the Americas, calling it a lie told to justify colonialism. They claim that human life originated simultaneously in the Americas, citing scientific evidence that is never fully presented and dubious at best.

At other times, Settler portrays secularism as a settler force of evil and argue for spiritual solutions, ignoring that early systems of colonial power were explicitly Christian.

The reason for these lapses may lie in the second 50 per cent of the text, that being the approaches the authors suggest for decolonization.

Rather than engaging in practical solutions, they ignore pragmatism and simply moralize. The solutions proposed are almost purely ideological. They propose the idea that, since Canadian sovereignty is immoral, colonialism can only be ended by abandoning imagined Canadian geographies and adopting pre-colonial indigenous ones.

This is, at best, a well-intentioned fantasy. It ignores the idea that, while colonialism needs to be reconciled, it can never be erased. In the same way that the Holocaust will forever inform Jewish identity, colonialism will forever be part of both indigenous and settler Canadian identities.

I can’t help but think of Wab Kinew’s book, The Reason You Walk, which approached similar subject matter from a personal perspective. He explored reconciliation through new and unified futures, not old and segregated pasts. It’s the kind of book that isn’t afraid to feel and to think, while Settler is more concerned with thinking about thinking.

Published in Volume 70, Number 11 of The Uniter (November 19, 2015)