Novel approach

Film showcase series examines literary adaptation

If you’ve ever wondered how your favourite book becomes your favourite (or least favourite) movie, you’ll want to add Cinematheque’s From Novel to Screen - The Writer’s Imagination to your calendar. The showcase series runs from Jan. 28 until May 27 and focuses on a selection of films featuring Canadian literary or cinematic connections.

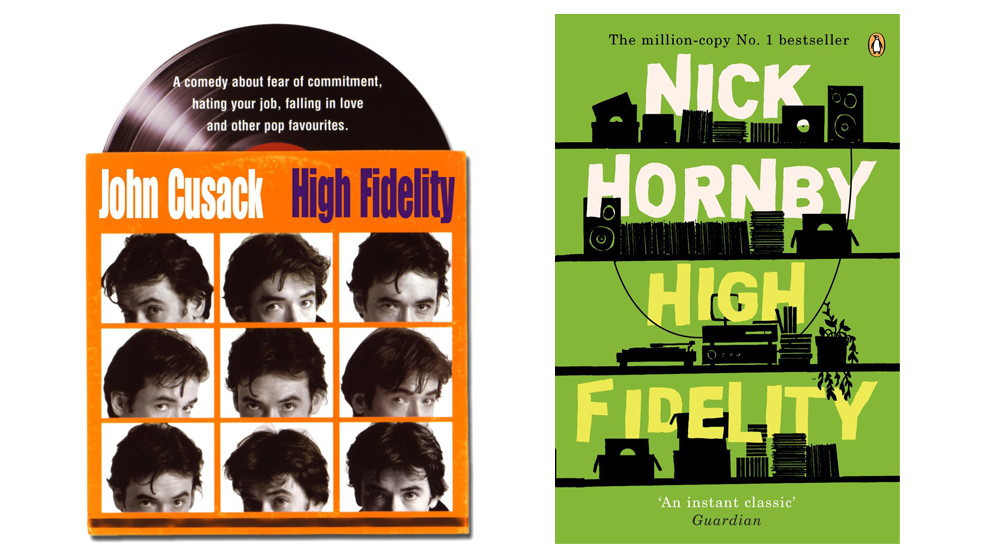

Selections include Alice Munro’s Away From Her, J.G. Ballard’s Crash and Mordecai Richler’s The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. Stephen Frears’ adaptation of Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity will also be included.

Winnipeg Free Press pop culture columnist Alison Gillmor believes readers have a clear idea of what they want from a film adaptation.

“You always hear: ‘Well, it wasn’t as good as the book,’” Gillmor says. “Yes, often the film isn’t as good as the book, but you have to accept film as a different medium. It can’t include every single important detail you want. It has to become its own thing.”

After each screening, Gillmor will lead a discussion examining the ways each film honours the literary original. Audiences are encouraged to read the novel in preparation for the discussion.

The pitfalls of literary adaptations seem endless. The adaptation can feel like a slavish imitation if it’s too faithful to the book. In other cases, a film simply falls short of expressing the emotional depth of the original source.

Many believe cinema to be the poor cousin of literature, as the novel comes first and is then adapted. George Toles, screenwriter and professor of film and literature of the University of Manitoba, is quick to correct this misconception. Toles notes that the subject can be difficult to discuss, as the theory on literary adaptations has advanced very little.

“It’s like we’re always reinventing the wheel,” Toles says.

While it’s not featured in this series, one example that’s synonymous with both classic film and literature is that of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, a novel that Toles deems unfilmable. Two filmmakers have attempted it, Stanley Kubrick, and Adrian Lyne, to varying degrees of success.

However, Toles does not discount the craftsmanship of these filmmakers. Instead, he feels that capturing the essence of the novel’s greatness would be impossible.

“The book is all Humbert’s voice,” Toles says. “Film has no way of creating an equally potent equivalent, in image and sound terms.”

Adaptations of novels that rely heavily on interior monologue often employ voice-over narration to externalize the internal, which Gillmor and Toles agree to be a poor solution. High Fidelity cleverly avoids this issue by allowing the protagonist to speak directly to the camera, to marvelous and endearing effect.

Toles cites The Godfather, a classic film adapted from a “somewhat pulpy” novel, as a classic example of an adaptation that surpasses its source material. Gillmor agrees, adding that Richard LaGravenese’s adaptation of The Bridges of Madison County drops the novel’s “horrible purple prose and replaces it with a leaner, tougher” screenplay.

George Toles will be joined by author David Bergen for a panel discussion on the subject of adapting novels for the screen on Mar. 22.

Published in Volume 69, Number 17 of The Uniter (January 21, 2015)