Lost Winnipeg

Urban renewal gone wrong: Lord Selkirk Park stands as a reminder of past planning mistakes

Do you love learning about our city’s past as much as we do? As part of a four part summer series, Robert Galston, author of local blog The Rise and Sprawl, will examine neighbourhoods’ transitions over the past century, up until the most recent 2006 Census. In May he took a look at South Point Douglas, and in June he visited Roslyn Road and the beautiful homes which once lined the street. This month, we learn about Lord Selkirk Park, a neighbourhood in the North End.

Of the transformations that changed the face and fabric of Winnipeg’s old neighbourhoods in the past 60 years, none have been as sudden, total and tragic as the development of the Lord Selkirk Park neighbourhood in the 1960s.

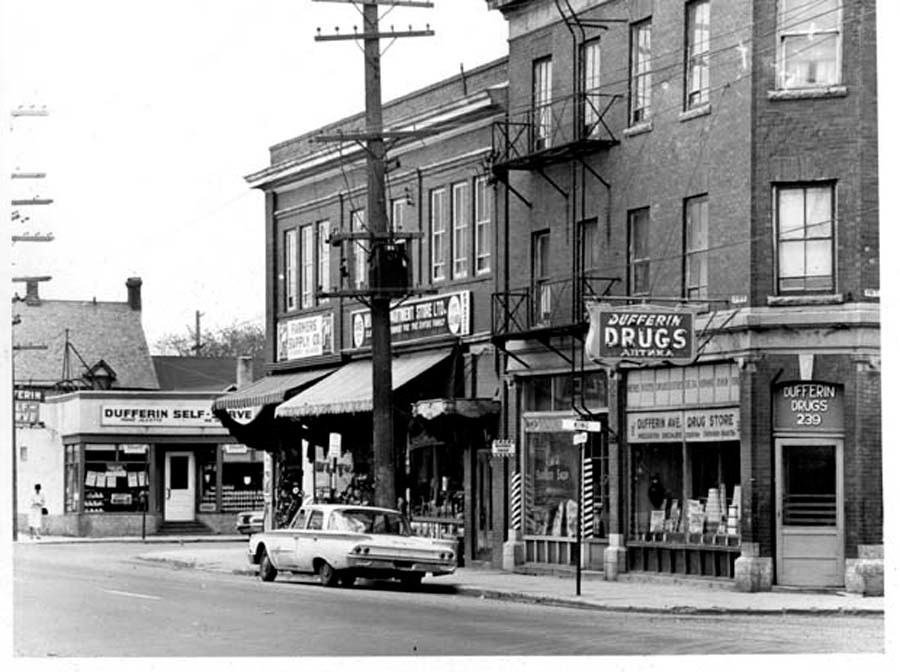

Centred around Lord Selkirk Park, a small park on Stella Avenue just west of Main Street, the neighbourhood was made up of small blocks gridded by streets with stuffy British names like Schultz, Derby, Jarvis, and Dufferin. By 1911, the neighbourhood had developed from the semi-rural edge of the city into a teeming neighbourhood of mostly Jewish immigrants. A streetcar line ran up Dufferin Avenue from Main to Arlington, and numerous commercial establishments dotted the neighbourhood, including the Dufferin Hotel, Levin’s Kosher Deli, Malkin’s General Store, and Dufferin Avenue Drugs (which prepared old country herbal remedies as well as modern prescriptions).

Beth Jacob synagogue was on Schultz and there was a farmer’s market on King Street.

“ By the 1970s, the social and physical conditions of the developments were worse than those of the “slum” they were intended to replace.

The neighbourhood was among the poorest in the city and had many instances of overcrowding and unsanitary conditions. Unlike the crowded immigrant quarters in larger cities at the time, made up of brick tenement blocks, much of the housing in Lord Selkirk was still ramshackle wooden places built on speculation in the early 1880s, or little backyard tenements – second houses built at the back of the lot.

Elizabeth Cam, whose recollections of growing up in the neighbourhood in the 1910s appeared in the Autumn 1972 edition of Manitoba Pageant, wrote that her parents called the neighbourhood “Mitzraim,” the Yiddish word for “Egypt.” But to Mrs. Cam’s father, who with his wife had escaped the pogroms in Russia years before, they could be doing much worse: “Thank God, here in Canada no one bothers us,” he told his daughter. “Here we are free to work… we have here the privilege to educate our children.”

As the second wave of Jewish immigrants that occupied the neighbourhood in 1911 established themselves in the new country, many were able to leave Mitzraim – if not for the Promised Land, then at least for the area north of Redwood Avenue.

In the 1950s, the city began looking at the idea of urban renewal, eliminating urban poverty by marrying suburban design to welfare state ideology, with the same violent intensity that Chicago, Baltimore and the Bronx were doing with their housing projects. And so Lord Selkirk was eyed for the massive new development. Val Werier, then with the Tribune newspaper, spent a week in the neighbourhood on the eve of its demolition in 1962 and, though he found much in the way of poverty and neglect, he noted how informal social contact and a micro-economy were able to thrive there.

The new developments were the local embodiment of everything about Modernist urban planning that Jane Jacobs decried a year earlier in The Death and Life of Great American Cities: a total separation of land uses, pointless and impractical green spaces, streets eliminated to create superblocks (14 blocks became three in Lord Selkirk), and the building of hyper-bland townhouses that look like they belong in Season One of HBO’s The Wire. Unsurprisingly, the pretenses of social reform only thinly veiled the plans of the city’s traffic engineers and the conceptual plans focused mainly on eliminating the urban clutter on Dufferin Avenue to allow cars to move faster.

By the 1970s, the social and physical conditions of the developments were worse than those of the “slum” they were intended to replace. Now there was no private property and few housing options. No more clothing stores, grocery stores, butcher shops and barber shops, meaning fewer eyes on the streets of the new superblocks and less of what is called “employment opportunities” and “skill-building” in contemporary social work jargon. The urban renewal scheme also created a major net loss of places to live in the North End and the Tribune reported that thousands of residents were displaced, finding themselves without a unit in the new development.

Walking through what was once the neighbourhood she grew up in, past where her father’s grocery store stood, which had since made way for a public insurance claims garage, Mrs. Cam hoped “that whoever might live [here] should know the happiness of work with freedom, growth with respect, and responsibility with love.”

While massive public housing projects, by their very nature and design, cannot offer happiness, freedom and responsibility to the urban poor, what Lord Selkirk Park does offer is a steady supply of good intentions from government officialdom, and a whole lot more grass. Isn’t that enough?

Published in Volume 63, Number 29 of The Uniter (July 16, 2009)