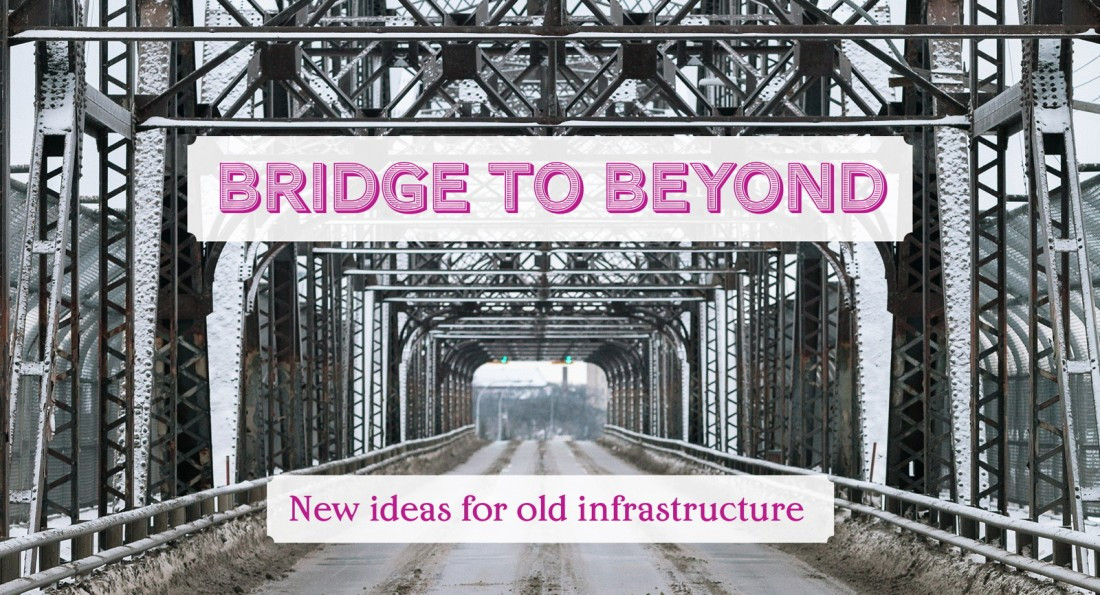

Bridge to beyond

New ideas for old infrastructure

Downtown Winnipeg seen from the top of the Arlington Bridge with the CPR y ards in the foreground. The Arlington Bridge seen from the Trinity Street railway crossing. The abandoned line framed by the Route 90 overpass.

The Arlington bridge, built in 1912, spans the CPR Winnipeg yards and connects parts of the West End with the North End. After a series of studies and open houses, the city hopes to come up with a new plan to replace the bridge before it reaches the end of its “useable service life” in 2020.

That might not have to mean tearing it down, Jino Distasio, director of the Institute of Urban and Inner City Studies at the University of Winnipeg, suggests.

“If you look at the Jubilee bridge, the BDI bridge as people like to call it, (my) father-in-law says they used to have two lanes of traffic coming at you. Now it’s a wonderful pedestrian bridge,” Distasio says. “We’ve got the old rail bridge at The Forks that is now a pedestrian bridge, we’ve got the one in Wolseley (Omand’s Park). We’ve converted rail bridges and automobile bridges in all kinds of places.”

The bridge has undergone many periods of major repairs, and was even cited as being at the end of its life before, in 1967. It took a few major hits in 2000 as well, with a set of train derailments that impacted the bridge’s major supports. It’s a piece of our infrastructure with a “storied history,” Distasio says – including some rumours that it was built to span the Nile River.

“Maybe there is some reason that we should retain it as part of an urban architecture piece,” Distasio suggests.

The rail yards that flow beneath the bridge and bisect the city are also under consideration by a separate working group, who are studying the possibility of relocating them just outside the city.

In the early days of rail travel, Winnipeg fought hard to be part of the rail lines, to secure their position as “Gateway to the West.” Within our urban context, long trains can delay commuters, create a lot of noise, and require infrastructure supports like overpasses and underpasses around rail lines.

Former Winnipeg Centre MP Pat Martin supported moving the rail lines, and replacing industrial lands with greenspace or a new central urban subdivision. Current MP Robert-Falcon Ouellette promised to make securing federal funding to move the rail yards as part of his election platform. But Distasio isn’t entirely sold on the idea of scrapping the yards.

“I was pleased to hear the task force is not simply stating the position that the objective of the task force is to relocate, it’s to assess relocation,” Distasio says. “What asset does having significant rail in our city bring?”

The appeal of rail fluctuates with pressures created by the price of oil, Distasio explains.

“It’s not that long ago that oil was way in the stratosphere and we began to think again more meaningfully about the long-term transition from oil to other sources of transit,” he says. “To have rail lines in our city, at some point, in a post-oil economy, might be seen more as an asset, or an asset lost, if we simply say rail is bad for cities.”

The old rail bridges, the simple and unchanged shape of train tracks, and the noisy beasts that lumber over them may look more like vestiges from a bygone era than a space of possibility for the future of our city. But perhaps in building a path to the future, we might consider not entirely scrapping the past.

Published in Volume 70, Number 17 of The Uniter (January 28, 2016)