A possibility, not a destiny

Calling out the collective preoccupation with parenthood

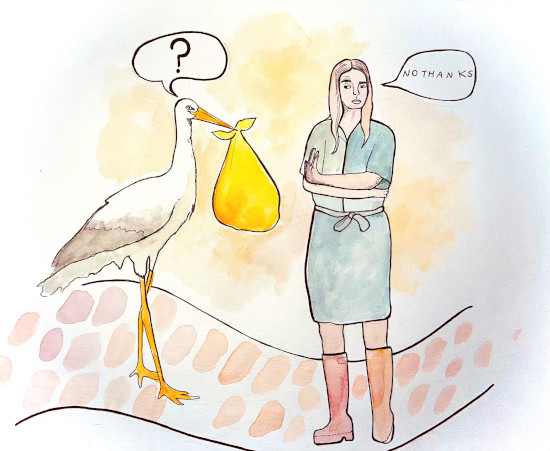

Illustration by Gabrielle Funk

Somewhere in storage, my sister-in-law has boxes of baby clothes stashed away for my future daughter. This hypothetical child and all her accoutrements also occupy space in other people’s minds.

My sibling jokes about when I’ll give her child a cousin. My students tell me I’ll be a good mom, a fun mom. A coworker going away on parental leave, my hairstylist, the stranger who sits next to me at a ballgame all ask if I’ve thought about having kids. As if I have a choice.

To them, my childlessness is temporary. I’m simply not a parent yet.

These assumptions drove every well-meaning “just wait until you have kids of your own” I heard as a preteen – and the “when you have kids, you can make the rules” I heard as a teenager.

They’re also more insidious.

According to a study published in 2023 in BMC Women’s Health, more than half of the surveyed 3,000 endometriosis patients reported being told that pregnancy might help treat their symptoms. For 89.4 per cent of those people, that advice came from healthcare professionals.

This is despite the fact that “there is a lack of evidence that pregnancy reduces

endometriotic lesions or symptoms” and that many people with endometriosis experience infertility.

I have adenomyosis, a similar condition, and rely on an IUD to manage my heavy, painful periods. Whenever my doctor pre- scribes and inserts a new device, he stresses how easy they are to remove – just in case I change my mind about having a baby.

This same doctor, relatives and acquaintances also tell me pregnancy and childbirth could mitigate my symptoms. They offer a baby as a treatment option, a decades-long commitment to temporary relief.

Lately, everyone’s curiosity, their comments, their prescriptions seem more urgent. It could be, at least inadvertently, because I turn 30 this year. People assigned female at birth experience their peak reproductive years between their late teens and late 20s – a fact I hear at almost every family dinner. I’m aging out.

But so are many parents. In 2019, the national average age for first-time mothers was 29.4 years old (and 27.9 in Manitoba). The average age at childbirth is now 31.6, according to 2022 data.

I married quite young (a few months before I turned 25), and many people still see a house and kids as the next logical steps. At the moment, I’m not interested in or able to afford either.

Canada’s total fertility rate is at an all-time low of 1.33 children per woman, according to Statistics Canada data. This may be due to pandemic-related job losses, prospective parents’ health issues, the skyrocketing cost of living or general uncertainty about the future, among many other factors.

I can’t definitively say I don’t want children, but I’ve never experienced a life where I didn’t have to consider that decision.

Despite all the unsolicited discourse about my hypothetical children, I’ve been thinking about them less. Instead, I’m focused on travelling, work, the possibility of going back to school, the growing list of titles on my Prime Video watchlist.

For now, becoming a parent is still a possibility, but it’s not my destiny.

Danielle Doiron (they/she) is the copy and style editor of The Uniter. Lately, they call Winnipeg, Philadelphia, Fargo and Canberra home.

Published in Volume 78, Number 18 of The Uniter (February 15, 2024)