A full doll’s house

Is artistic adaptation the way to keep classic plays fresh and new for modern audiences?

Shakespeare, Ibsen and Brecht were all masterful playwrights. But as societal views change, are the meanings of our classic plays getting lost in the passage of time? And if so, how are we to keep the classics relevant in the modern age?

University of Winnipeg theatre professor Tom Stroud’s unique interpretation of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House forces us to explore these ideas.

In his recent Winnipeg Fringe Festival production, Stroud cast five actresses – all on stage at the same time – to play the part of Nora. It was an absurdist twist on a highly-regarded realist play written in the late 19th century.

This interpretation not only raises these questions, but also what limit, if any, there is to artistic license in play adaptation.

Stroud’s answer is that there is none.

“I think that it’s completely open. The only thing that restricts imagination is budget, and I think that one should be as inventive as they can be within the practical environment that they’re in,” Stroud said.

He does, however, add one exception: “The key is serving the author’s intent.”

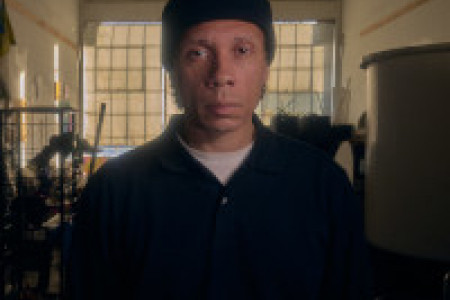

Christopher Brauer, professor of theatre and film at University of Winnipeg, agrees.

“The beauty of adapting classic work is that nobody’s holding a gun to your head,” said Brauer. “So really it comes down to the adaptor’s moral sensibility in terms of honouring the playwright’s message.”

So what was Ibsen’s message?

“I think he was drawing attention to the dilemma of the women in his time. I think he strongly believed that men and women are essentially different and that the patriarchal society that they were living with did not honour the integrity of women,” Stroud said.

Of course, we live in a very different time than Ibsen lived in; back then, the idea of a woman walking out on her husband was unprecedented and unheard of.

“ The beauty of adapting classic work is that nobody’s holding a gun to your head.

Christopher Brauer, professor of theatre and film at University of Winnipeg

“From a modernist/feminist perspective, it would be very easy to dismiss certain aspects of the texts because it is quite dated. So I like to use style and absurdist twists to freshen up the text and give a new perspective on it.”

Brauer sees adaptation as necessary for many classic plays.

“While they’re beautifully written and beautiful poetry, they were written for a different era, they don’t speak directly to our era, so they just become fodder for massive adaptations so that they can speak to the issues or matters that directly affect the now.”

Stroud’s background in dance and theatre served him in using choreography to unite the five actresses in portraying one woman when they were all on stage together. However, at points in the play, there was only one actress portraying Nora at a time; a very deliberate move which twisted the play just enough that the audience didn’t expect what they saw.

“[Bertolt] Brecht… and other theatre thinkers would say: The way to get people to see something is to make it strange,” said Brauer.

The five women conveyed the side of Nora that was dependent upon her husband who was only engaged in superficial kinds of pursuits, Stroud said.

“When I needed her to speak more from her heart, or get to the underside of her real feelings, that’s when I used just one Nora.”

“At those times when she is just one thing, it made her a very powerful presence,” Brauer said.

Published in Volume 63, Number 30 of The Uniter (August 13, 2009)