A different reality

Community is what separates us

The world came to a halt for Cooper Nemeth’s family and friends this February, and as a city, we grieved.

Like many tragedies involving a young person and drugs, this one began many conversations: conversations about family, about police presence, about drug use and, with one 14-year-old’s letter, Winnipeg was prompted to think about this tragedy from an Indigenous perspective.

After police and civilians alike banded together to find Cooper, Brianna Jonnie wrote a passionate and frustrated letter to the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS), detailing what they should do if she is ever missing. As an Indigenous girl, Jonnie lives in a different reality – one where going missing isn’t that farfetched.

Jonnie expressed that the police don’t do enough to look for Indigenous people. In a widely publicized reply, Cooper’s dad Brent said that their family didn’t get special treatment from the police – they relied on a committed network of family and friends.

But not everyone has that. And even if Jonnie does (her letter indicates a good home life and support system), as an Indigenous girl, she belongs to one of the most targeted groups in the city. That’s not an exaggeration. APTN recently reported that three out of four murder victims in Winnipeg this year are Indigenous women.

Shocking as those stats are, the story wasn’t nearly as circulated as Brent’s response to Jonnie’s letter.

As a city we hear about Indigenous women going missing, and young women like Jonnie know it’s happening. But the news doesn’t appear in our feeds unless we make an effort to put it there. The media might cover an exceptional story, but missing Indigenous women is not an exceptional topic. Yet when Cooper went missing, there was no way to miss the story and it was shared by strangers and friends alike.

We rarely see that coverage happening for young Indigenous women – not when they go missing, nor when they are found dead. We don’t see community centres filling up with determined searchers, armed with Tim Hortons coffee and donuts and handfuls of flyers. Maybe those stories aren’t as newsworthy, but why not? As Brent said in his reply, Cooper had a lot of friends. Maybe he was involved in more things, touched more lives than these other people. But that’s not the whole story.

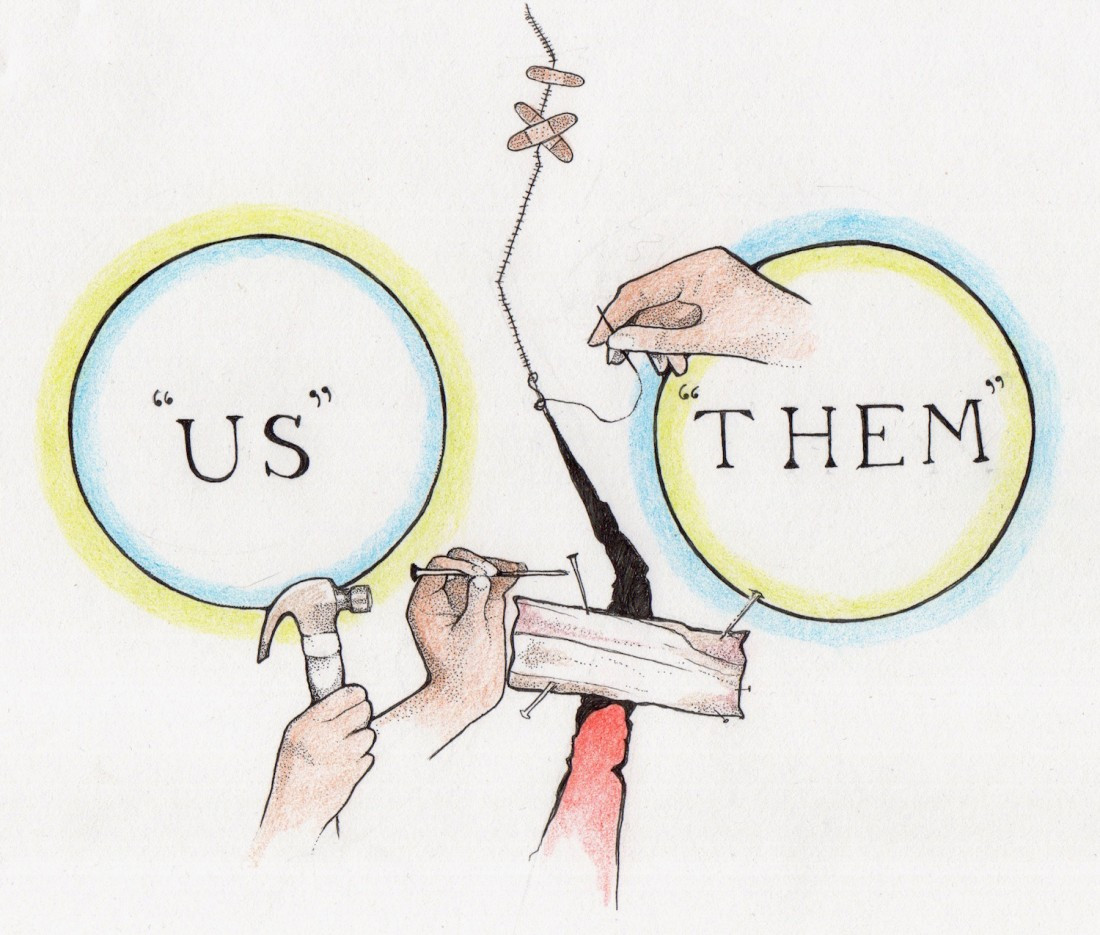

There is still a huge rift in how Winnipeg reacts to missing Indigenous women and how we react to missing people like Cooper, a young white male who was on the hockey team. And while Jonnie was inspired to write to the police by what happened to Cooper, we shouldn’t take it from his dad that they didn’t receive special treatment. They didn’t – the support, respect and community that they had during their tragedy was probably not a departure from what Cooper’s life had been up to that point.

But for too many of Winnipeg’s residents, that is not the norm in good times or bad. Not everyone can rely on what Cooper’s family had, so they have to rely on the police.

As a community of Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents, we should keep pushing the police, the way Jonnie is. We should keep pushing because for many of Winnipeg’s residents – those who may be isolated or struggling with poverty – the WPS is the first and last line of defence. There is no curling hall full of supporters. In fact there may be a lot of people pointing fingers and blaming the victim or their family.

We are drawing lines about what we will and won’t accept, Winnipeg. And we can do better.

Alana Trachenko is the Volunteer Coordinator at The Uniter. She also writes at alanatrachenko.com

Published in Volume 70, Number 25 of The Uniter (March 24, 2016)