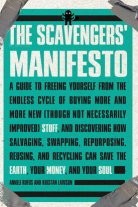

The Scavengers’ Manifesto

Mass consumption is an unsustainable practice. The earth upon which we live will not be able to absorb the waste we so callously throw its way.

These environmental truisms percolate throughout our daily lives. The global environmentalist discussion is now firmly entrenched as a topic of social interest.

Last year though, the growing fears of climate change were trumped mightily by the rising tide of worldwide recession. After the dust had settled, a new truism emerged from the rubble of un-repentant capitalism: Living beyond one’s means has to stop.

It is at this intersection of the environment and the economy that Anneli Rufus and Kristan Lawson present their intriguing new book, The Scavengers’ Manifesto.

Capitalizing on the recent surge in popularity of thrifty living, the book details a number of ways in which people can go about acquiring material goods beyond traditional consumption methods. These methods run the gamut from the relatively tame – shopping at discount stores – to the relatively extreme – dumpster diving – all of which the authors place under the heading of “scavenging.”

By casting the net of scavenging wide, Rufus and Lawson are able to present a compelling argument as to how it is that scavenging for economic and environmental reasons is a part of the lives of most human beings.

Part social history and part how-to guide, the book provides a fairly broad array of information on how and why anyone can come to incorporate methods of scavenging as an alternative to shopping for goods at full price.

Basically, the argument is that if something can be found for cheap (or better yet, for free) then there is little reason to pay full price like our corporate masters compel us to. However, due to the notorious history of the act of scavenging, the authors devote a good chunk of the book to disputing the stigma surrounding the term.

While their tour through the rudimentary historical factors for discrimination against human scavengers is interesting, it should have been assumed that the audience of this book already wouldn’t have a problem with the label. Where the book suffers is in its over attentiveness to cleansing the image of scavenging for a mainstream audience who will probably never read it.

But this is a partial criticism, for the sweeping history of scavenging certainly is interesting.

From the social castes of India to Dharma Bums-era Jack Kerouac to present-day coupon clippers, many apparently fall within the scavenger category, where the only requirement is that paying for overpriced merchandise is to be avoided at all costs.

Social history comes at the expense of a strong argument as to why scavenging practices should be adopted, raising suspicions as to the manifesto-ness of this offering, but the nature of the book’s focus creates many fun facts for readers to enjoy.

Yet, if it is a strong argument against the capitalist economic system you are looking for, steer clear from this one. The authors understand that their scavenging habit relies on waste which other people produce, waste gleaned from the very system which they subvert.

So while it likely won’t win over any new converts, The Scavengers’ Manifesto certainly does provide a wealth of information for those already partial to the cause.

Published in Volume 64, Number 11 of The Uniter (November 12, 2009)