The rising tide of Indigenous Storytellers

HighWater Press is publishing Indigenous histories in new ways

Shortly after confederation, the Red River Resistance saw Indigenous peoples in Manitoba organize and take action for their rights in the face of the Canadian state.

Today, First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples play a central role in creative cultural expression and resistance in Manitoba. Indigenous peoples’ creative works are a part of the province’s cultural fabric, and this role carries on today with a variety of young writers, artists and storytellers.

Within this whirlpool of creativity and action is HighWater Press, an imprint of Portage & Main Press that focuses on sharing the stories of Indigenous peoples from the perspective of Indigenous creators. The publisher helps Indigenous creatives use storytelling to educate people in Manitoba and around the globe on the lives of Indigenous peoples.

Owner and publisher Catherine Gerbasi says HighWater had to start in Manitoba’s capital.

“How could we not start the press (in Winnipeg)?” she says. “It is Treaty 1. It is the heart of the Métis (nation). Winnipeg has the largest Indigenous population in Canada. It is a very young, creative, active and driven community.”

While HighWater Press remains small, it has been making waves with releases like the award-winning graphic novels This Place: 150 Years Retold and A Girl Called Echo: Pemmican Wars.

Managing editor Laura McKay-Keizer points out that as the publisher gains momentum, its foundation remains the same.

“Portage & Main is one of the oldest publishing companies in Manitoba, and it has always been Canadian, independent and woman-owned,” she says. “It is really something special.”

The dam bursts for Indigenous storytellers

Some of the works published by HighWater Press and Portage & Main Press on display at the companies’ office in Winnipeg's Exchange District.

Mary Dixon purchased the company in 1994 and renamed it Portage & Main Press. Dixon increasingly focused on publishing the work of Indigenous creators and attained the publishing rights for Beatrice Mosionier’s In Search of April Raintree, as well as the stories of groundbreaking Salteaux writer and broadcaster Bernalda Wheeler.

When Gerbasi purchased the company in 2007, she felt as if Indigenous stories were already a part of the publisher’s history. For this reason, when author David Robertson came to Portage & Main with a graphic novel on the story of Helen Betty Osborne, Gerbasi jumped at the opportunity to showcase a new Indigenous writer and his way of telling stories.

“It was a turning point. It was a realization that these stories were being told in new ways,” Gerbasi says.

HighWater Press was founded in 2009, after Robertson’s book was published, to further spotlight Indigenous literary creators. Since then, the publisher has focused on fostering the creativity of Indigenous authors. The authors and the publishers maintain a symbiotic relationship, growing together to share more with a wider audience.

“When we talk about the history of HighWater, we can’t separate the creators who we met,” Gerbasi says. HighWater “formed its own identity and its own mandate: to publish the work of Indigenous writers.”

Gerbasi feels HighWater has come at the right moment to capture a growing Indigenous arts scene in the city. Authors who have worked with the press, including Katherena Vermette, Chelsea Vowel and Robertson have all become critical creators in the legacy of Manitoban writers.

“It was a surge or renaissance of creativity among Indigenous creators, writers, intellectuals, academics, educators that all seem to be surging forward at a particular time. We were fortunate enough to capture that burst of energy, to be a part of that community,” Gerbasi says.

New ways of telling

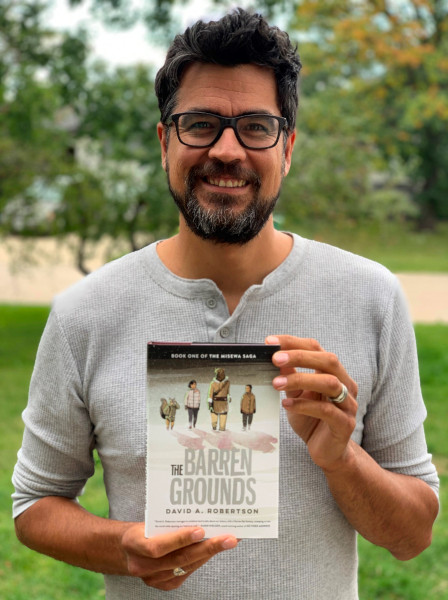

Author David A. Robertson has published dozens of books through HighWater Press and Portage & Main Press. (Supplied photo)

“I decided to do graphic novels because they had just done so much damage in the past in how they have misrepresented and stereotyped Indigenous people,” Robertson says. “I just felt like you might as well fight fire with fire and tell good stories about Indigenous people that are accurate.”

Graphic novels are a central part of HighWater’s collection and make up a bulk of their output. McKay-Keizer emphasizes that the value of graphic novels lies in the medium’s combination of words, pictures and literacies.

“Graphic novels tell stories using multiple different literacies in a way that novels and short stories don’t. So when you are reading a graphic novel, you are looking at your verbal literacy, your visual literacy, spatial literacy, iconography,” McKay-Keizer says.

She also draws attention to the gutter, the space between comic panels, and how it can be used to create empathy between audiences and the content they read.

“As a reader, you are projecting yourself into the story. You are filling in the gaps,” McKay-Keizer says. “Part of that process means that you are a lot more engaged in the text ... That means that you have a higher level of empathy for the main characters.”

She says the sense of empathy graphic media can create is useful when readers from different backgrounds approach these stories.

Teaching Indigenous stories

HighWater has an identity separate from its parent company but shares a common goal of education.

“Education has changed in the past 15 years, and the integration of Indigenous studies into the curriculum has benefitted and driven HighWater’s growth,” Gerbasi says. “It is important for teachers to find content to teach the subject matter and the (curriculum) outcome. We were very purposeful about selecting and developing titles that would meet curriculum expectations.”

HighWater primarily puts out works that are geared toward grade-school students. However, this fact has not stopped their texts from entering post-secondary education.

During 2019’s One Book UWinnipeg event, local professors taught the same book, HighWater’s graphic anthology This Place: 150 Years Retold, and visiting speakers presented on the text.

As a part of the project, Dr. Julie Pelletier, an anthropology professor at the University of Winnipeg, taught This Place in her classes as a companion piece to traditional textbooks.

“The first reaction, for the most part, is shock and dismay, like, ‘This is supposed to be a university class ... Why would she be giving us a comic book to read?’” Pelletier says. Now, though,

Pelletier says many students will likely remember more from This Place than a typical textbook. Pelletier echoes McKay-Keizer, emphasizing the value that comes with readers having to engage in several critical literacies when reading graphic novels.

“In the classroom, (students) were accustomed to just reading text ... and I said what about the images ... I could walk them through the colours, the style,” Pelletier says.

Gerbasi says education is critical for bettering Indigenous relations in Canada and reiterates the words of Murray Sinclair, “Education got us into this mess, and education will get us out of it.”

The future for HighWater

David A. Robertson says he was inspired to write comic books and graphic novels to combat negative stereotypes of Indigenous peoples that had been historically perpetuated by the medium. (Supplied photo)

In terms of the future, the press has begun to feature more women writers to bring their stories into the fold. McKay-Keizer also wants HighWater to share works that break convention with protagonists that resolve problems in new ways.

“We’re publishing stories that aren’t seen in the media,” she says, “stories that are adding to the (larger) narrative ... and voices you haven’t heard before.”

While HighWater focuses on sharing Indigenous histories, McKay-Keizer makes it clear that these stories are not just historical.

“We definitely look for very compelling stories, but we try to look for stories that are very contemporary, that speak to recent events that are experienced now. Indigenous people live here in the present, and their lives are also in the present.”

Published in Volume 77, Number 10 of The Uniter (November 17, 2022)