Rooster Town: the Winnipeg community that nobody remembers

Researchers team up to unearth unique history from city’s not-so-distant past

Believe it or not, the Grant Park area of Winnipeg wasn’t always a mecca for moderately priced restaurant chains, jaywalking teenagers and convenient parking.

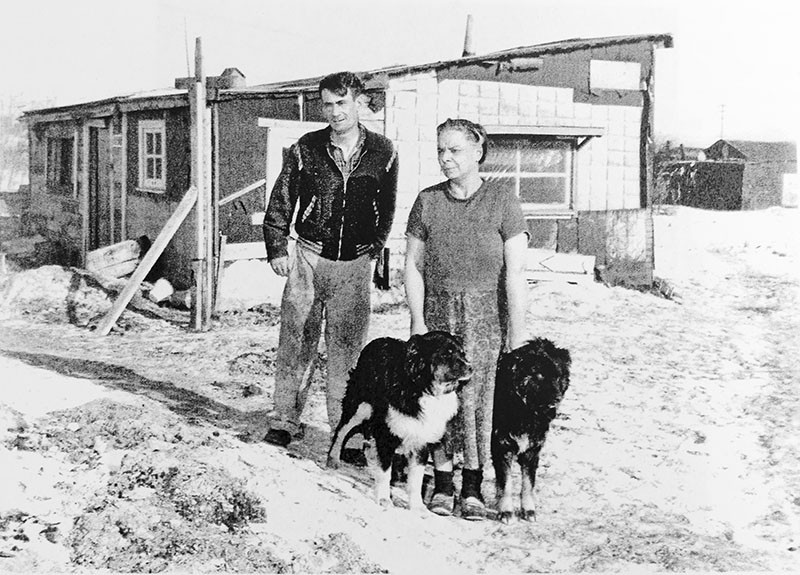

As recently as the late 1950s, the space sandwiched between Grant Avenue and Taylor Avenue, and extending from Wilton Street west until Lindsay Street, was occupied by the now-little-known bush community known as Rooster Town.

Now, the Manitoba Métis Federation and the University of Winnipeg are partnering on a research project aimed at gathering first-hand accounts of the lost community.

“The newspapers talked in a very pejorative way about the people,” said Lawrie Barkwell, senior historian at the Manitoba Métis Federation’s Louis Riel Institute, referring to the predominantly poor, Métis community whose homes were largely comprised of self-built structures made from boxcar lumber.

“But it was far from the ‘Wild West’ that people often portrayed it as,” he continued, noting Rooster Town existed before the advent of social housing. “It was a working-class community with a vibrant culture. These weren’t welfare families or squatters.”

According to Barkwell, Rooster Town first cropped up around the turn of the century, but experienced much of its growth during the Great Depression.

The community’s unique name likely derives from the many seasonal railroad workers that “roosted” in the settlement at various times of the year.

The project is already receiving stories from individuals who responded to the project’s call for first-hand accounts of the bygone community, which went without electricity and running water for the entirety of its relatively short existence.

“ They gave everyone $50 and then they kicked them out. Then they built a big mall and the property developers got to make money off of it.

Lawrie Barkwell, senior historian, Louis Riel Institute

“We’ve had stories from people who, as kids living in the nearby neighbourhoods, used to go play games with the Rooster Town kids all of the time,” said Barkwell, adding he too would play in the area as a child.

However, the distinctive culture Rooster Town had built around itself over the course of decades took little time to wipe away in favour of more economically lucrative plans set out by the city’s government.

According to Barkwell, during the late ‘50s the settlement’s residents were “expropriated” from their homes so the land could be developed.

“They (government officials) gave everyone $50 and then they kicked them out,” said Barkwell. “Then they built a big mall and the property developers got to make money off of it.”

Manitoba Métis Federation Winnipeg vice-president Ron Chartrand says the story of Rooster Town offers insight into contemporary issues.

“(Residents) were ostracized from the rest of the (Winnipeg) community because they were of aboriginal descent,” said Chartrand. “But they persevered despite the stereotypes that were unfairly applied to them, and that are still so often applied today.

“We’ve made headway over the years towards being recognized as our own people and as our own culture,” Chartrand continued. “There’s more of awareness now about the struggles faced by the Métis people.”

According to a university release, Peters and Blackwell plan to write a history of Rooster Town and may consider doing a documentary on the settlement.

To share your story, contact Barkwell at 204-984-9480 or by email at [email protected].

Published in Volume 67, Number 9 of The Uniter (October 31, 2012)